Dutch painters of the 17th Century were the first European artists to start painting landscapes, because land was owned by commoners as well as by nobles. Throughout the history of art, the subject matter that was most depicted was an indication of what was most important at the time. The newly freed Dutch had no king, and the various new Protestant churches had no single religious authority as previously exercised by the Catholic church. The Dutch became the merchants and tradesmen of Europe, and most trading ships sailed into the port of Amsterdam, where goods were then distributed to the rest of Europe. The Dutch owned their land and their homes, and they looked for small works of art that would fit on the walls of their small homes. The people, rather than the church or state, became patrons of the arts, and a thriving art market developed as a result. Three new subjects were added to painters’ repertoire: genre (paintings of everyday life), still life, and landscapes. European artists frequently painted horses and dogs since they were commissioned by the wealthy owners. Even though the Dutch were responsible for initiating landscape painting, ordinary farm animals were painted by a very few artists, but those artists were masters.

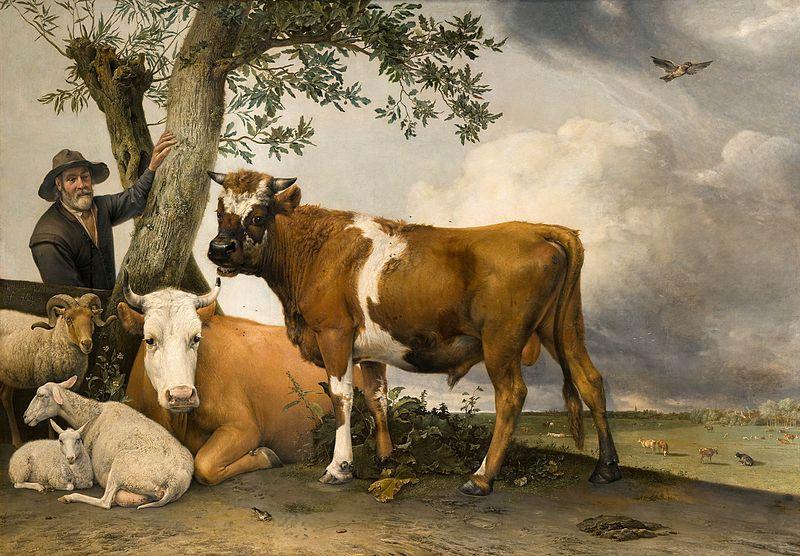

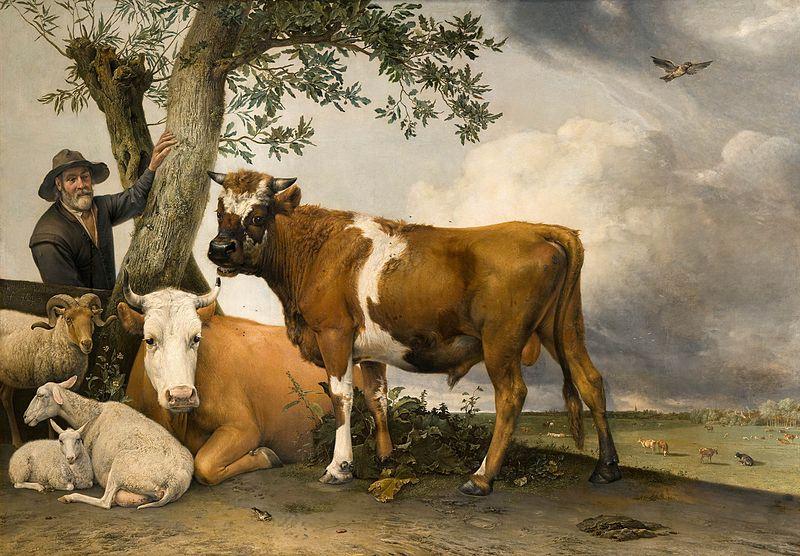

“The Young Bull” (1647) (93” x 133”) by Paulus Potter (1625-1654) was considered to be one of the best Dutch landscapes; landscape painting including animals was Potter’s specialty. The bull was considered a symbol of prosperity by the Dutch, and it represented strength and confidence. This painting is an exceptionally large painting for the time. Potter added canvas to both sides and the top after it was finished in order to include other animals. Potter added a cow, the symbol of fertility, motherhood, and nurturing. Likewise, the ewe supplies milk for many Dutch cheeses. She protects her lamb, a symbol of innocence and gentleness, and reminded viewers of the lamb of God. The ram represents virility and is known for its determination and agility when climbing hills. These animals were as significant to the prosperous life of the Dutch as they are today. The landscape depicts the Dutch town of Rijswijk. A herd of cows graze peacefully on the green pasture. Potter also captures the flatness of the Dutch landscape and the cloudy sky that will bring rain to the land.

Chickens, ducks, and other foul were valued for their eggs, feathers, and meat. “Seven Chicks” (1665-68) was painted by Melchior de Hondecoeter (1636-1695), a Dutch painter who specialized in bird studies. The “Seven Chicks” includes several poses, colorings, and head studies of baby chicks. The artist captures the lopsided walk of one chick, two feeding chicks, a nesting chick, and baby chicken heads from various views. The sketch shows his exceptional observational skill and his devotion to his beloved subject matter.

De Hondecoeter’s “Ducks” (1675) depicts several species of ducks and a white dove. Among the various birds represented by the artist were brent geese, Egyptian geese, red-breasted geese, fieldfares, partridges, pigeons, ducks, northern cardinals, magpies, peacocks, African grey crowned cranes, Asian sarus-cranes, Indonesian yellow-crested cockatoos, Indonesian purple-naped lory, and Madagasgar grey-headed lovebirds. The port of Amsterdam bought a wide variety of exotic plants, spices, and birds to Holland. It is easy to understand why this period is known as the “Dutch Golden Age.”

“Young Boy Looking into a Pigsty” (1749) was painted by English artist George Morland (1763-1804). Although his works include a variety of subjects, he was famous for his genre scenes, many including farming and hunting. He was inspired by “Dutch Golden Age” paintings. Three pigs rest in the straw in a sturdy pigsty. The standing pig enjoys a leafy green nibble, and the viewer can see a large carrot placed diagonally in the right corner. Although pigs are usually thought to be dirty animals who love to roll in the mud, these well-nourished pigs are clean and comfortable. They appear to be well cared for and will someday provide a nourishing dinner. Resting his arms on the gate, a little boy admires the pigs. All is well.

“Guinea Pigs” (1792), also by George Morland, depicts three pets nibbling on a large green leaf. Symbolic of friendship and community, the guinea pigs are comfortably grouped together. Guinea pigs were introduced into Europe in the 16th Century, and they became favorite pets from then on. They were frequently depicted in history, myth, and religious paintings to represent the importance of social connections. They are small and soft, like to be cuddled, make a whistling sound when they are happy, and purr like cats. Morland’s painting is the first known painting of guinea pigs, and it is generally considered one of the finest paintings of any animal.

There were not many master painters of Europe who specialized in animals, but those who did excelled. “Two Rabbits” (1841) by Rosa Bonheur is a charming painting. Bonheur is best known for her large-scale paintings of horses, plowing scenes, and other working animals. Her paintings brought her wealth enough to purchase the estate at By, where she kept a menagerie that included a lion. Her love of animals both large and small is apparent in this delightful painting of rabbits. Like other animals, rabbits have a symbolic meaning; they are known for their fertility and therefore represent abundance and prosperity. The lucky rabbit’s foot has a long history in many cultures. Bonheur’s painting, like others in this article, simply lets the viewer appreciate and enjoy the scene.

This article is inspired by the exhibit celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Kent Clover Calf 4H Club, the oldest continuously chartered 4H club in Maryland. The exhibit is on display at the Bordley History Center (Kent County Historical Society) in Chestertown.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Gerry Early says

This is a wonderful series. We are lucky to have The Talbot Spy with Beverly Hall Smith as a contributor.