Born in 1791 in Charlestown, Massachusetts, Samuel Findley Breese Morse was raised by Jedidiah Morse, a well-known minister and supporter of Calvinism and Federalism. Samuel was an “eccentric” student, but he did graduate from Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and graduated (Phi Beta Kappa) from Yale in 1810. He studied religious philosophy, mathematics, and science. However, he began his career painting miniature portraits, and he worked as a clerk in a Boston book store. His interest in art was discouraged by his father, who finally relented and supported Samuel going to England (1811) to study with the American painter Washington Allston. He remained in England for three years, met the prominent American painter Benjamin West, and his artistic talent earned him admission to the Royal Academy in London in 1811. His “Self- Portrait” (1812) (10.75’’ x 8.85’’) evidences his skill as an artist. It is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

During his three-year stay in London, Morse produced several paintings in the popular Neo-Classical style based on Italian Renaissance realism and history and mythology. “Dying Hercules” (1812) and “Judgment of Jupiter” (1814) were well received in London. However, Morse was well aware of the issues that caused the War of 1812, and felt the Federalists, who supported England in America “were cowards, a base set, [I] say they are traitors to their country and ought to be hanged like traitors.” During the presidency of Monroe, the Federalist party collapsed.

Morse returned to America in 1815, and he established residence in Greenwich Village in New York City. Americans were not interested in history or myth, and he began as an itinerant portrait painter. Notable early portraits were of president “John Adams” (1816) and “James Monroe” (1819). Adam’s portrait is in the Brooklyn Museum, and Monroe’s is in the White House. Morse painted portraits of other famous Americans including Eli Whitney (1822), De Witt Clinton (1826), William Cullen Bryant (1829), and Noah Webster (n.d.).

The Marquise de Lafayette was an American celebrity after his participation in helping to win the American Revolution. Morse’s “Marquise de Lafayette (1825-26) was commissioned by the City of New York. The two men discussed the Revolution, and their friendship strengthened Morse’s already significant embrace of America and democracy. George Washington and Lafayette were fast friends, and Lafayette’s pose is reminiscent of the 1780 portrait of Washington by Charles Willson Peale.

Lafayette stands on the top step of a porch. A flourishing landscape and a dramatic blue sky with turbulent red, gold, and dark clouds provide the backdrop. Instead of creating a stormy effect, the rose glow of a sunset after a storm gives a sense of power and presence to the figure of Lafayette.

The porch has an inlaid marble floor, with stone balcony railings and a large carved vase. The new shoots of a leafy vine growing from the vase perhaps represent the young Democracy. Three stone pedestals at the left hold busts of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. A third pedestal, on which Lafayette rests his right hand, is empty. Likely, it was intended as a tribute to Lafayette, who someday would have his bust placed there to mark his accomplishments.

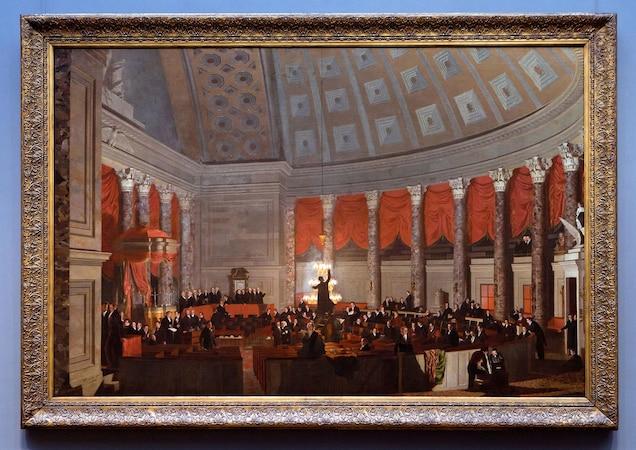

Morse painted “The House of Representative” (1822) (7.5’ x 11’) (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). The commission for four panels for the Rotunda of the Capitol would pay the artist $10,000. Morse traveled to Washington to make an accurate drawing of the House architecture with 80 people in the chamber. Morse choose to set the scene at night to illustrate the dedication of the house members to their work. The painting was exhibited in 1823 in New York City, but it was not a success. John Adams questioned if an American artist was up to the task. Morse’s close friend James Fenimore Cooper wrote a letter, published in the New York Evening Post arguing the Capitol would be an “historic edifice” and must showcase American art. The painting was not chosen, and Morse blamed Daniel Webster and John Adams, a Federalist, who voted against it.

Morse married his first wife Lucretia in 1818. “Mrs. Morse and Two Children” (1824) depicts her with their two children Susan and Charles. Morse chose a classic triangular pose, with a dark column placed behind his wife. He encircles them with a dark red shawl and darker green in the left background, and the cushion and Lucretia’s skirt. However, he centers the tender interaction of the three figures in a soft, pastel palette of the Rococo. To match their rosy pink cheeks and light clothing, Morse paints a soft blue and pink sky. Lucretia tenderly embraces baby Charles, an active and delighted child. Susan happily plays with a bubble pipe.

The love of his wife and children is evident in this painting. Attached to the painting was a letter Morse wrote just before leaving for Washington in 1824: “A thousand affecting incidents of separation from my beloved family crowded upon my recollection. The unconscious gayety of my dear children as they frolicked in all their wonted playfulness, too young to sympathize in the pangs that agitated their distressed parents; their artless request to bring home some trifling toy; the parting kiss, not understood as meaning more than usual; the tears and sad fare wells of father, mother, wife, sister, family, friends; the desolateness of every room as the parting glance is thrown on each familiar object, and farewell, farewell seemed written on the very walls, — all these things bear upon my memory, and I realize the declaration that the places which now know us shall know us no more.” Unfortunately, Lucretia died in 1825, soon after the birth of their second son James.

Morse was a founder of the National Academy of Design in New York City, and he served as its first president from 1826 to 1845. The Academy became the center of the arts in Greenwich Village. Returning to Europe in1831, Morse decided to paint “Gallery of the Louvre” (1831-1833) (6 ft. x 9 ft.). The painting includes 38 miniatures of works by Renaissance and Baroque masters. He thought this painting would be an excellent teaching tool for his students and an introduction for Americans to the splendors of European art. The work took months, and Morse moved a scaffolding he invented around the Louvre in order to have a closer look at each painting. Masterpieces by da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, Tintoretto, Caravaggio, Rubens, and Rembrandt are among the works included. The miniature of the “Mona Lisa” is placed in the center of the canvas on the lowest row of paintings. The fourth painting in the row is of Rubens’s beloved second wife Suzanne Fourment. Morse’s recent loss of his own wife might have influenced the placement of the Rubens portrait.

In the foreground of the canvas, Morse leans over the shoulder of his daughter Susan giving her advice concerning the drawing she is sketching. At the left, Richard Habersham, a young artist from Georgia and a roommate of Morse’s in Paris, is working on a landscape study. In the left corner are James Fenimore Cooper and his wife and daughter Susan, an art student seated in front of her easel and holding a palette. Cooper was a long-time friend, and spent many days with Morse in the Louvre. He described his time with Morse: “I sit and have sat so often and so long that my face is just as well-known as any Vandyke on the walls. Crowds get round the picture, for Morse has made quite a hit in the Louvre, and I believe that people think that half the merit is mine.”

In the arched doorway is the American sculptor Horatio Greenough and a women and child in traditional Briton costumes. Greenough, hat in hand, looks across the gallery to the ancient sculpture of “Diana and a Deer,” placed on a pedestal in the right corner. A young woman, wearing a gold gown, sits at a table painting a miniature. She may be Miss Jorester, a young woman who took lessons from Morse in the Louvre, or his deceased wife Lucretia. The figures were added to the canvas after Morse returned to New York.

Morse exhibited “Gallery of the Louvre” in New York City on August 9,1833. The work received critical praise, but it sold for only $1300. Morse had hoped for $2500. When Morse did not receive a commission from the Government to paint one of the history panels in the Capitol building, he became depressed: “Painting has been a smiling mistress to many, but she has been a cruel jilt to me. I did not abandon her, she abandoned me.” “Gallery of the Louvre” sold in 1982 for $3.5 million to the Terra Foundation for American Art in Chicago.

The name of the artist Morse and the name of the inventor of the telegraph and code Morse are the same. Morse did abandon art, and he turned to science. A talk he had heard years earlier at Yale (1810) inspired him to use the wooden canvas stretcher bars from his studio to construct his earliest version of the telegraph. After a great deal of trial and tribulation, Congress funded wiring American from coast to coast, and Morse received a patent in 1844. Morse purchased in 1847 the estate Locust Grove on the Hudson River. In 1848 he married Sarah Elizabeth Griswold. They had four children.

On May 24, 1844, Morse sent his partner Alfred Vail the first telegraph message from Washington to Baltimore: “What hath God wrought.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.