Humans were hunter-gathers more than 1.8 million years ago. Animals were the source of food, clothing, and shelter, all necessary for survival. When nobles and kings became the landowners in the Middle Ages in England and France, hunting certain animals became their sole province. William the Conqueror brought French “forest law” to England, setting boundaries where hunting was restricted to the King and members of the nobility.

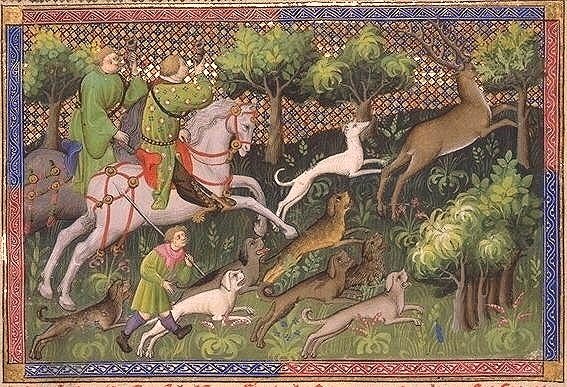

“Deer Hunting” (1407) (10’’x7’’) is an illustration included in Le Livre de las chasse (Book of Hunting) by Gaston Phoebus (1331-1391), published after his death. Holder of the title Comte de Foix, Phoebus was an important man in both politics and the military. He was described as sophisticated and known for this elegant household. He owned 1600 dogs and 200 horses. In one of the first manuscripts on the subject of hunting, Phoebus described the proper weapons to be used when hunting specific animals: For large animals such as bears, wild boar, and deer, sharp pointed arrows that will penetrate deep into the flesh are appropriate. For rabbits, an arrow with a large lead head should be used to stun without cutting into the body.

The two hunters in the manuscript are dressed in green, often used in hunting clothes in order to blend into the forest. Both blow hunting horns used to communicate during the hunt. Goat, sheep, and cow horns, and elephant tusks were used. Hunting dogs could be trained to the horn calls. In French “chasse par force des chiens” (the chase by strength of hounds) used dogs to locate and stalk the deer. The animals to be hunted were enclosed in large royal parks and guarded by gamekeepers/foresters. Hunts included a long chase, killing and butchering the deer, and a banquet. The chase was seen as a test of a man’s strength and courage, and it was considered the noble form of hunting. The ritual was intended to be dangerous, but in a controlled setting.

Behind the deer is a leaping greyhound. It was favored for its speed and ability to attack and bring down a deer. However, it lacked the stamina for a long chase; it was released only when the deer had been spotted. The greyhound also was considered a noble dog, and it made a good pet. Other dogs were alaunts and mastiffs. Alaunts would also attack domestic animals and even their owners. The breed is now extinct. Mastiffs were hardy, but also were gentle and often used as family guard-dogs.

“Landscape with a Hunter” (1873) (81’’x121’’) was painted by Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), a French painter responsible for the style of Realism. He stated, “Painting is an essentially concrete art, and can consist only of the representation of things both real and existing.’’

Courbet began showing hunting scenes in the Paris Salon in 1857. He was an avid hunter and told his friend, “It is an excuse for some violent exercise that I am rather fond of.” His hunting paintings often contained detailed views of dead animals. “Landscape with a Hunter” is tame compared to other of his paintings on the subject. Courbet was an excellent landscape painter who developed the use of the palette knife to give texture to rocks and tree trunks. In this green summer landscape, the hunter kneels behind a large rock and watches as the two deer approach the stream.

Hunting scenes became one of Courbet’s most popular subjects. After the French Revolution and Napoleon (1801-1814) the royal privilege of hunting had been abolished. As a result of concern about the decimation of species and damage to forests, hunters were required to obtain permits which also came with restrictions. Courbet’s realistic hunt scenes found both praise and criticism. They presented a realistic and somewhat disturbing image of the hunt. The also displayed a sympathy for animal suffering. The Société Protectrice des Animaux was founded in France in 1845.

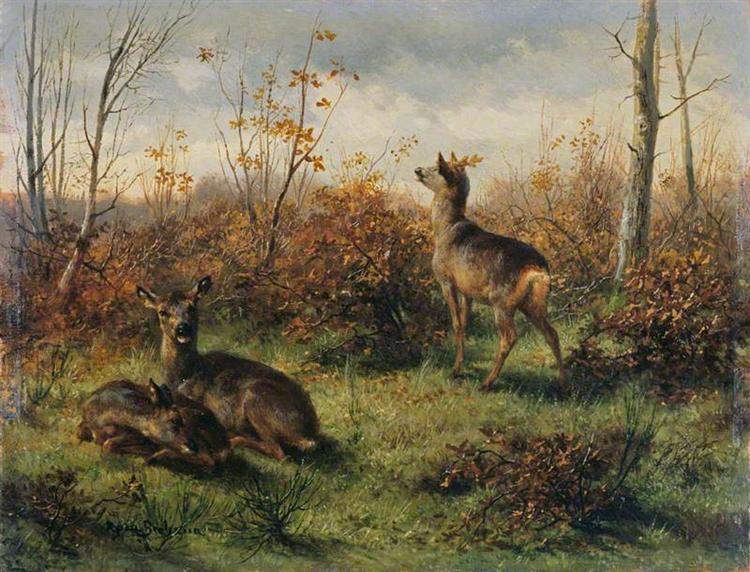

One of the most celebrated painters of animals in the 19th Century was Rosa Bonheur (1882-1899). Unlike Courbet, who relished the sport of hunting, Bonheur cared for a wide variety of animals on her large estate. Among them were deer, wild sheep, a gazelle, rabbits, horses, and a lioness named Fatmah. “Roe Deer” (1860) (19”x25”) (oil) is a depiction of the most common deer. Roe are smaller deer, and as seen here, the male deer has short antlers. In this composition the male deer stands with his nose raised up and appears to be surveying the distant landscape. The female deer turns her head toward the viewer, and she makes eye contact. The third deer sleeps peacefully. Bonheur has selected a fall day with a gray sky; some trees still retain their orange leaves, while others have not. The variety of browns in the coats of the roe deer has been carefully observed, as have their black noses, white chins, and white rumps.

In “Stag on the Watch” (1883) (9’’x12’’) (drawing in watercolor and pencil) Bonheur depicts a magnificent male red deer, a stag. As Bonheur observed, red deer have no spots on their coats, and they have a tan rump and no tail. The red deer is largest of the deer species. A stag’s antlers can reach over three feet and weigh as much as 33 pounds. Placing the stag in a fall landscape and posing him on the alert, head up and legs ready to run, was a reminder that it was hunting season.

In the Middle Ages the red deer was known as a hart, and it was the most highly prized of all deer. Symbolically, the hart was the deer St. Hubert and St. Eustache saw with the cross of Christ between its antlers. Both saints became patron saints of hunters. (refer to “The Feast of St. Hugo,” Chestertown SPY, November 9, 2023)

In “Monarch of the Glen” (1886) (29’’x24”) (oil) Bonheur brings the viewer face-to-face with three stags in a fall forest. A monarch is the single and absolute ruler of a state or nation. Given the long respect and devotion for deer over the centuries, it is not a surprise that they were frequently referred to as monarchs of the forest. Bonheur’s paintings of animals made her an exceptional woman artist. She received many awards from France and other countries and became a wealthy woman who lived life as she chose. She stated, “If we don’t always understand animals, they always understand us.”

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.