“Remembering the Name of Slaves” Darlene R. Taylor

Heirlooms are defined in dictionaries as “valuable objects that belonged to a family for generations.” The word “valuable” in that description is highly subjective. Such objects likely have value to family members or descendants. But they may or may not have monetary as opposed to sentimental value. “Darlene R. Taylor: Heirlooms,” at the Academy Art Museum, is an oddly resonant reflection of 18th- to early 19th-century free black families of the Hill neighborhood of Easton – all of them women – depicted with their backs to the viewer, ensuring their anonymity, which defined the lives of most African-American women, free or enslaved, in pre-Civil War America.

Taylor, a black woman born in 1960, has created a series of mixed-media collages, some of which are near life-size, incorporating vintage cotton, linens, laces and even buttons handed down mother to daughter mostly, but also cousin to cousin or friend to friend. Artifacts from excavations commissioned by the museum of the long-ago home of Henny and James Freeman, who headed one of the earliest free land-owning black families in Talbot County from 1787 to 1828 are part of Taylor’s motifs that almost invite touching, which of course is not allowed. The fabric-on-paper derivations are so homey they seem drawn directly from unfinished work from a sewing basket. For me, the most tempting piece to reach out and feel its domestic textile hand-me-downs is “The Children of Slaves Remember,” 2023.

Taylor says her archival works reflect untold stories of “the love, labor and thriving of black life and family.” The Freeman home and adjoining properties on Talbot Lane just behind the museum are being repurposed for much-needed administrative space.

Full disclosure regarding a possible personal connection: I grew up on a farm next to what is now Chesapeake Easton Club East on Dutchmans Lane, where I now live in retirement. From age 5 in 1952 to when I attended and graduated from the University of Maryland College Park, that farm remained my home-away-from-college. My mother taught a young man named James Freeman to read. He worked on our farm until my parents sold it in the mid-’70s. Freeman was a common name for children or grandchildren of former slaves. But I wonder now if the gentle farmworker I knew as James Freeman back in the 1950s to ’70s was a descendant of the free land-owning black family next door to what is now the Academy Art Museum.

Sometimes, it seems like an awfully small world when you move back to your childhood hometown.

***

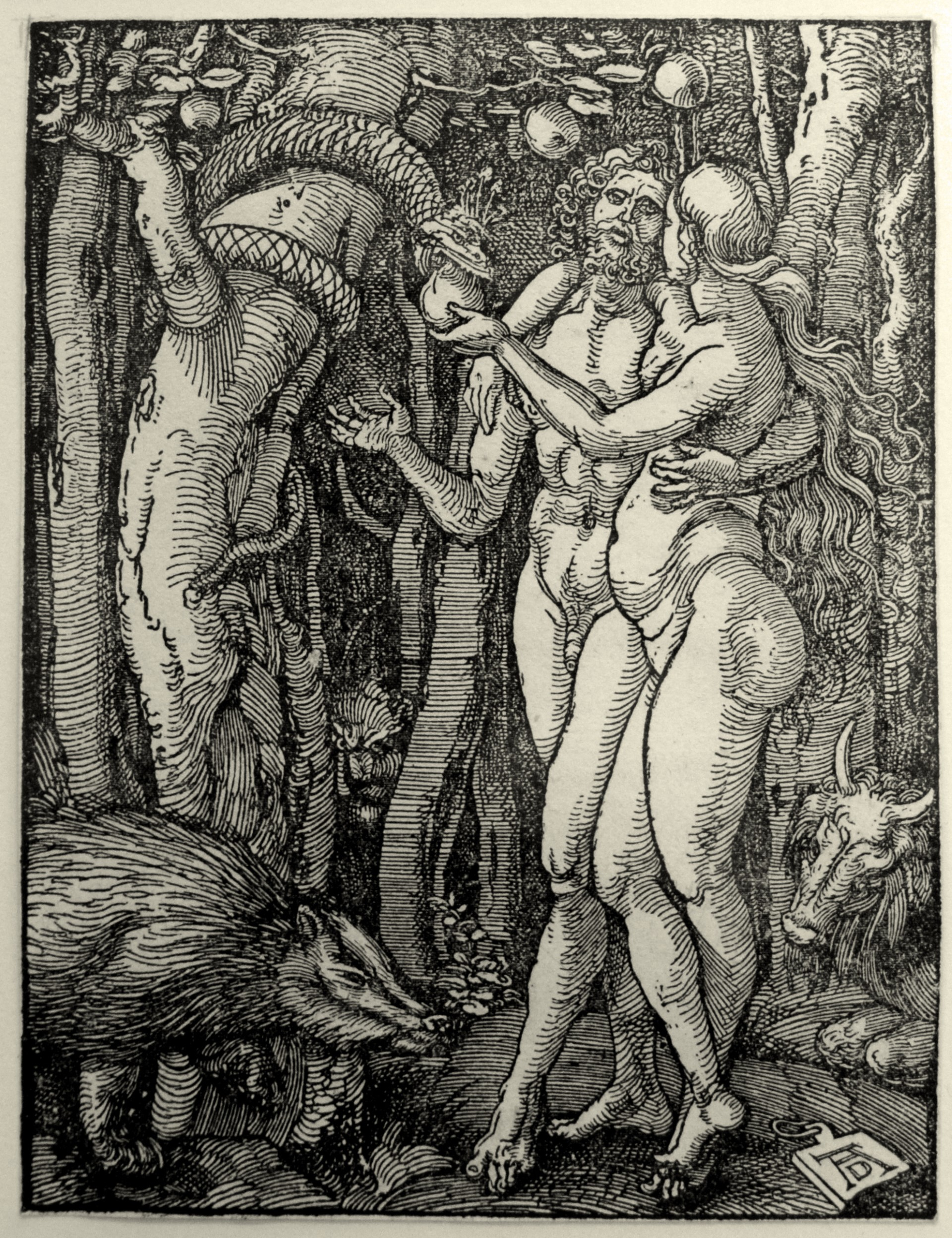

“Fall of Man,” Albrecht Durer

An important collection on loan from the Reading Public Museum in Pennsylvania of works by Albrecht Durer, the Renaissance artist who revolutionized European printmaking in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, fills the two small first-floor AAM galleries.

You’ll see a copy of a color print of young Durer with an introductory wall label summarizing his career that made him one of the most notable artists of his time. Hanging next to the portrait are magnifying glasses that you should use in the next room. There, on the far wall, you’ll see 16 remarkable prints from Durer’s “Engraved Passion” series depicting the final days in the life of Christ. All the New Testament scenes described in the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are there – among them the kiss of death by Judas, Pontius Pilate washing his hands as Jesus is found guilty, the crown of thorns affixed on Jesus’ head on his way to the cross, his Crucifixion and of Christ resurrected with a halo of illumination above his head. The magnifying glass makes a great difference in viewing these engravings not much larger, if at all, than baseball cards. The magnification brings their incredibly detailed imagery into stark focus. The technique reveals the delicate intricacies that distinguish Durer’s engravings from the earlier woodcuts that are also masterpieces – including his “Fall of Man: Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise.”

Returning to the first gallery, don’t miss the posthumous portrait of Durer by Erhard Schon, dated 1538. Durer died in 1528 at age 56.

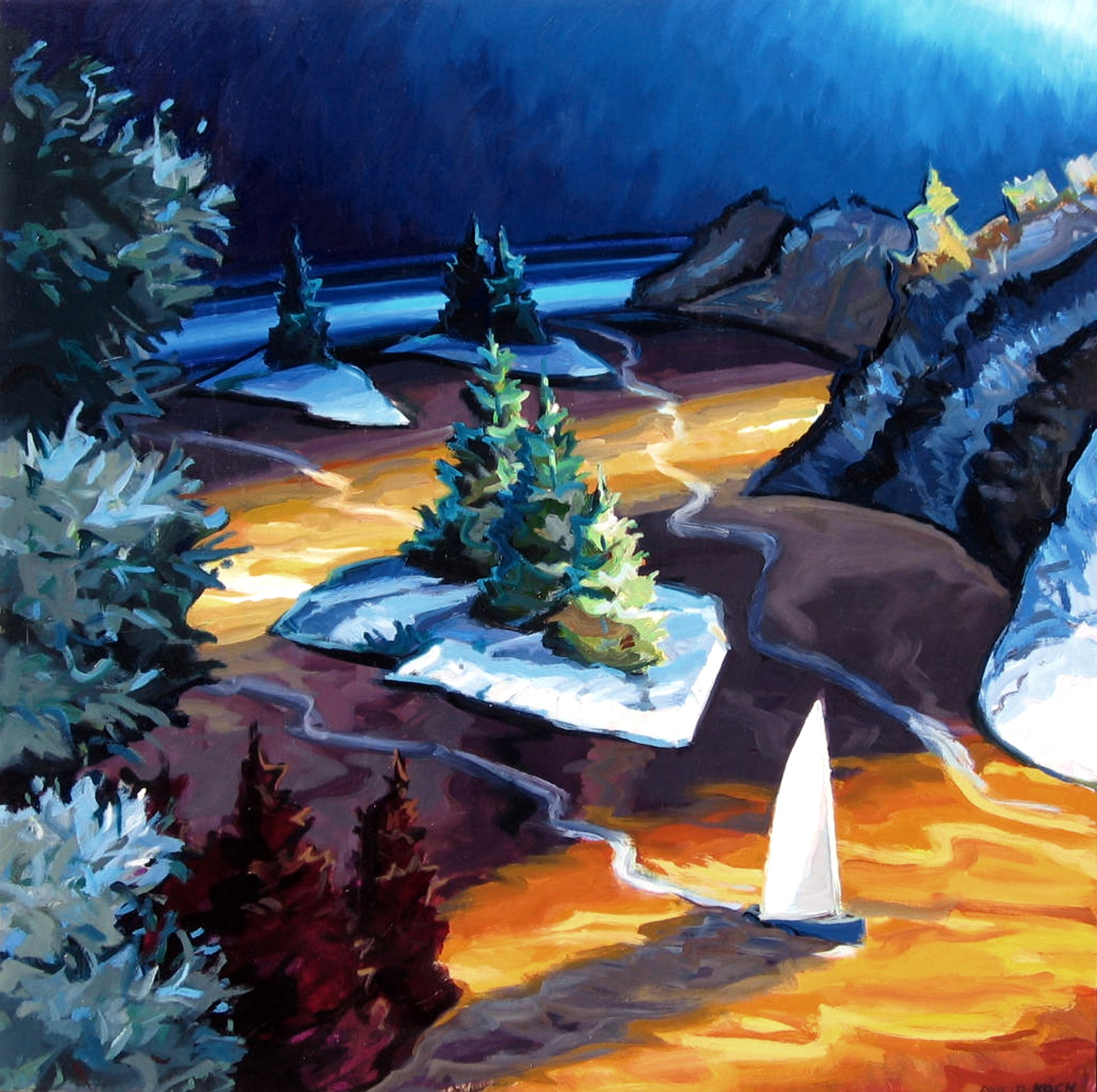

“The Voyage of Memory,” Philip Koch

Philip Koch, like many American artists born in the mid-20th century (1948), was very much influenced by abstract painters who were all the rage at the time. But then he met realist artist Edward Hopper, born in the previous century (1884), who died in 1967 at age 84. There was still time, however, for Koch to be taken under Hopper’s wing and, posthumously, earned him an unprecedented series of residencies – 17 of them – at the elder’s Cape Cod studio and access to the Edward Hopper Art Center in his Nyack, N.Y. birthplace. That changed the arc of Koch’s career from abstract to stark realism in landscapes and architectural detail. You’ll notice his fondness for Mansard rooflines in the current Koch exhibit at AAM. Switching in style from his previous landscapes, represented in this show with a few paintings from the early ’80s, Koch began producing colorful picture-postcard scenes as opposed to flora abstractions of his imagination.

Whether or not you see this as an improvement in his artistry may depend on your taste in paintings. Hopper’s influence on Koch’s later works is unmistakable, though it strikes me as somewhat more imitative than creative. But then, there’s nothing wrong with pretty pictures.

With four shows going on at once, not counting Marty Two Bulls Jr.’s “Dominion” installation that went up in AAM’s entry hallway months ago – there’s a lot to take in. But don’t skip the charming little exhibit upstairs, “Remnants of Childhood,” curated by teen interns who selected art from the museum’s permanent collection. My runaway favorite is Austrian artist Ossi B. Czinner’s “Man, Moon, Umbrella” interpretation of Jack jumping over the candlestick. Or, for local flavor, you might want to check out Claudia DeMonte’s “Shrine to Maryland” mixed-media diorama adorned with blue crabs that turn red when you boil them, reminding us that it pays to be head of the food chain.

Four New Exhibits at AAM

“Darlene R. Taylor: Heirlooms,” “Albrecht Durer: Master Prints” and “Light: Paintings by Philip Koch,” all through July 14. Also, “Teen-Curated Exhibition: Remnants of Childhood” through June 9, all at Academy Art Museum, 106 South St., Easton. academyartmuseum.org

Steve Parks is a retired New York arts critic and editor now living in Easton.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.