In a world where selfies are as ubiquitous as the cell phones they are taken on, it’s refreshing to view self-portraiture as something other than expressions of vanity. Not that the artists whose works comprise the latest major exhibit at the Academy Art Museum are not, or were not in their time, as vain as any of us. But, by and large, each has something more to say than “Hey, look at me.”

“Fickle Mirror: Dialogues In Self-Portraiture” encompasses myriad techniques for rendering portrayals of one’s self, including, yes, self-photographic prints. A few portraits were created centuries before print photography, not to mention iPhone face capture. At the very start, if you begin in AAM’s Lederer Gallery, you’ll encounter Self Portrait with Plumed Cap and Lowered Sabre, a 1634 etching on paper by Rembrandt von Rijn from the Easton museum’s permanent collection. Unlike many of young Rembrandt’s earlier self-images, this one has him posing as an invented character, reflected in the next self-portrait, a 1987 drypoint etching by Pat Steir. Twinned selfies separated by centuries are repeated with Francisco de Goya y Luciendes’ 1799 aquatint, echoed in Emily Lombardo’s 2013 etching, which is all but a likeness of Goya’s except for his top hat.

Next, it’s impossible to miss South African-Canadian Evan Penny’s super-realistic (though larger-than-life) silicone busts titled Young Self: Portrait of the Artist as He Was (Not), Variation #2 with lots of hair and Old Self: Portrait of the Artist as He Will (Not) Be (also variation #2) with far less hair and way thicker eyeglasses.

From this riveting experience, your gaze will turn next to a 1986 quadrant of Andy Warhol silkscreen self-portraits with his hair ablaze, or at least electrified. Way more impressive is one of several portraits on loan from the Art Bridges Foundation established by Alice Walker, founder of the Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Ark., the home base of Walmart. Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s I Refuse to Be Invisible depicts in ink, charcoal, and acrylic with Xerox transfers the Nigerian-American artist dancing with her white husband in race-conflicted USA, showing her dark face to us in a proud 2010 interracial narrative.

Mequitta Ahuja’s 2012 acrylic and watercolor painting Mocoonama keeps that narrative going in a powerfully primitive art statement (no disparagement meant by the term “primitive.”). Turning a corner, Amy Sherald’s 2003 Falling From Grace oil is best seen by standing back from a distance to decipher the figure in distress as she tumbles in what I took as a pre-dawn atmosphere. Sherald is best known for her portrait of former First Lady Michelle Obama, previously on view at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Among the most digressive in the self-portrait theme is American Paul Villinski’s steel sculpture of a male figure in interlocking open rings resembling a human-shaped chain-link fence. In his see-through belly, we notice a bird’s nest. I can’t say I get it. How about you?

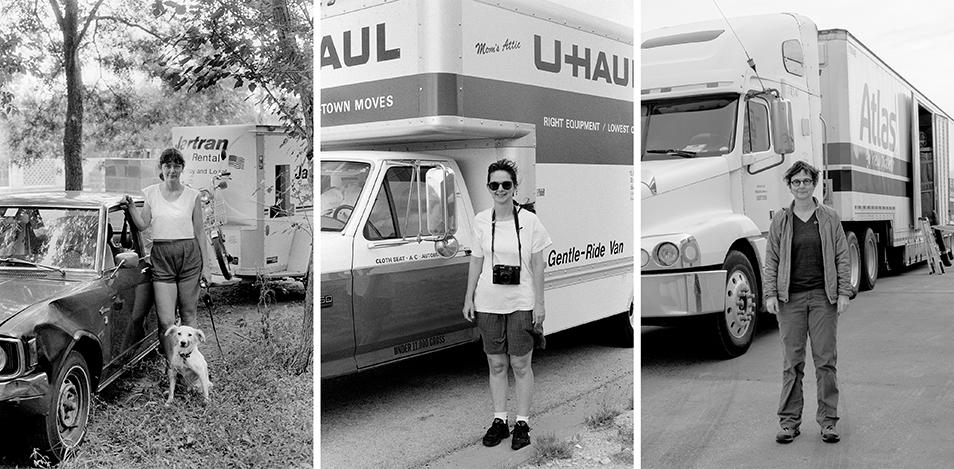

Across the hall, in the Healy Gallery, black-and-white serial portrait narratives by Nancy Floyd dominate – too much, in my opinion. But I appreciated her commentary, probably intentional, on Americans’ acquisitive predilections in the black-and-white photo series, Moving 1983-1999-2018. In each succeeding frame, the artist’s vehicle of means progressed from a trailer to a U-Haul truck to a full-fledged moving van.

Anchoring the Healy Gallery is Turkish-American Mehmet Uskul’s Blending In, a dream-scene panorama of a man in a jungle setting with a chameleon on his hand who may be transmitting green skin tones to his human host. Lush flora and fauna offer soothing distractions from the painting’s underlying turbulence. Make of it what you will. But take a moment to pause and take it in.

***

Jackie Milad, Academy Art Museum’s 2022 artist-in-residence, exhibits her vividly chromatic mixed-media collages in “Vestige,”ß which poses the question: “How do narratives of belonging shape us?” Milad’s works in the two small galleries down the hall from the AAM auditorium reflect her identity as a Baltimore-based Honduran-Egyptian-American woman. Historical symbols of both Honduran and Egyptian cultures – pyramids, in particular, built by Central American Mayans and by African slaves of the ruling class of pharaohs are glimpsed in many of her bright and bold compositions rendered with paint on paper or canvas, often hung like a fabric. Adding cutouts, textile ornamentation, and purposely crude drawings, Milad creates a visual dialog linking ancient architectural references to the short-lived human experience represented by eyes, hearts, and facial features. Milad, who led a collage workshop the day after the show’s opening, will create new works during her summer residency in Easton. Meanwhile, you can have some fun with her exhibit by participating in a scavenger hunt for symbols hiding in plain sight within her collages. Just pick up the bright-colored handout as you enter the gallery.

***

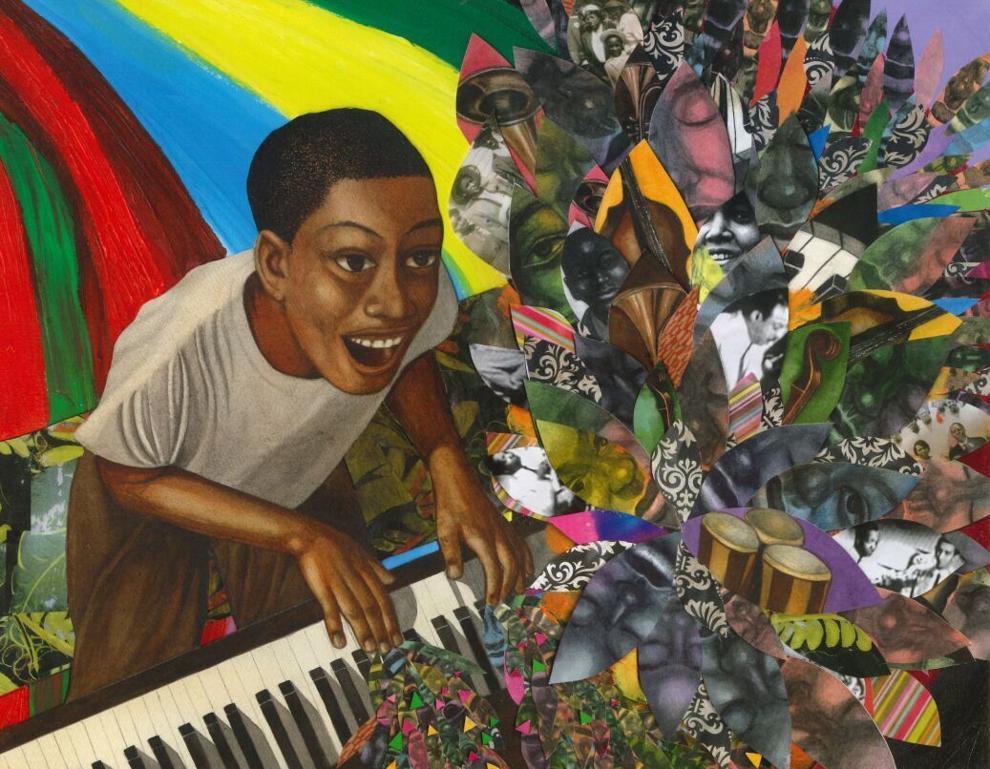

Upstairs in the museum, “Bryan Collier: Dream Walking” has been extended to the Sunday before Labor Day. The multi-award-winning children’s book illustrator from Pocomoke City is exhibiting paintings for his latest book project, “Music Is a Rainbow,” loosely based on the childhoods of poet Maya Angelou and musician/producer Quincy Jones.

Illustrations from three other books – “By and By,” “I, Too, Am America,” and “We Shall Overcome,” referencing poems by Langston Hughes and lyrics by Pete Seeger, round out this poignant representation of youthful African-American life and dreams.

Steve Parks is a retired New York arts critic and editor now living in Easton.

Academy Art Museum

“Fickle Mirror: Dialogues in Self-Portraiture,” through Oct. 10.

“Jackie Milad: Vestige,” through Nov. 13.

“Bryan Collier: Dream Walking,” extended through Sept. 4; 106 South St., Easton, academyartmuseum.org

Steve Lingeman says

Well done review !