True to its title, “Intimate Generations,” is achingly intimate, personal and moving. Curated by Tara Gladden, the Kohl Gallery’s new Director and Curator, and on view at the Kohl through February 29, this exhibit kindles a multitude of emotions, deep memories and realizations about how family influences and profoundly affects our personal identity and view of life, yet it also ranges far beyond personal stories into the hidden bonds that connect us all.

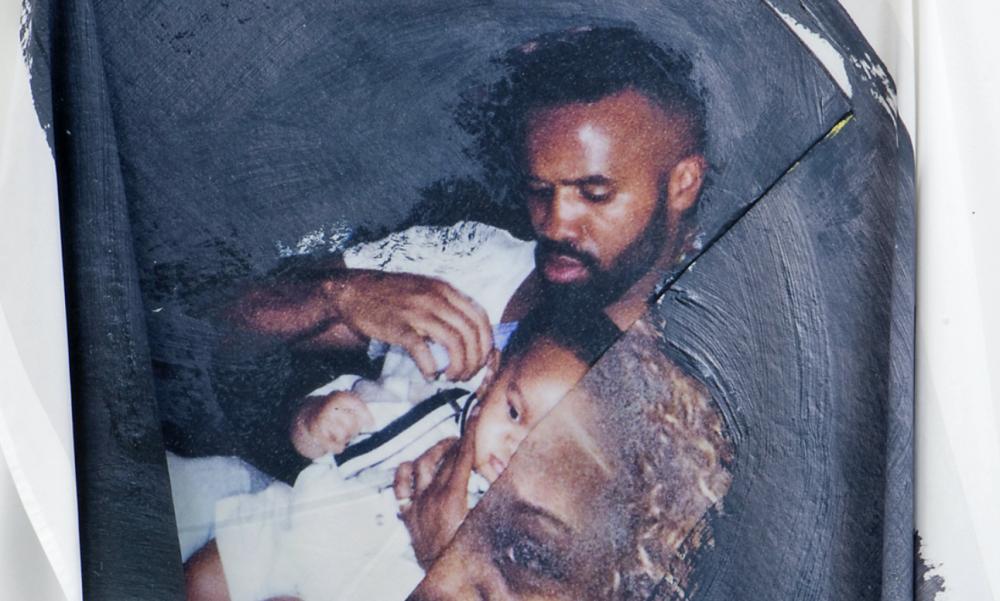

There’s a wonderful fusion of generations in “My Mother, My Father and I” by Prince George’s County artist Kalen Na’il Roach. Spliced from old family photos, parents and child are merged into one warm brown and black form with the child (the artist as a toddler) snug in the center. In another reworked photo, radiating lines scratched into the surface of a snapshot of his mother intensify the lively energy in her smile, while patches of color swiped on with paint markers make the space around his father hum as he poses for the camera. Shot in the family’s home, these are casual images, comfortable and brimming with familiarity, yet Roach’s abrupt cropping and slashing gestures indicate that there’s more. These photos can’t tell the whole story—there are mysteries present. Certainly, family is the bedrock of existence, yet it is full of unknowns, things about our closest relatives that we may never know or understand.

The bonds of parent and child are explored on an even more intimate level in Philadelphia artist Aimee Gilmore’s “Sleep Series” and “Milkscapes.” Using her own breast milk, she poured luxurious, stunningly intricate forms onto paper or photos. They call to mind primordial patterns of creation, whether swirling galaxies, surging lava flows or meandering streams and rivers. While some are digital prints capturing the spectacular details of these spills of the nutritious milk, in others, actual breast milk spreads across the surface of a shadowy images where infant and mother slumber in a milky dream, the physicality of their bond underscored by the puckering of the paper under the flowing liquid.

One of the strengths of this show is that it views family relationships from many angles. While Roach and Gilmore explore the closeness and trust between parents and children, chanan delivuk, of Baltimore, documents the inevitable truth that love begets pain. While still in her teens, delivuk was startled by her own lack of understanding of her mother’s emotional and mental state when she read the journal her mother wrote to cope with her deep sadness, uncertainties and vulnerability. Touched by her grandmother’s suffering and decline, the loss of her father, and her own guilt over inadequacies as a parent, delivuk’s mother had been internalizing her pain. Pages of the journal are reproduced for this show, interspersed with ghostly medical imaging of her mother’s heart from a hospital stay for surgery. Strikingly reminiscent of Gilmore’s milk spills, these images are haunting proof that while technology allows us to actually see the heart, it can’t tell us what that heart is feeling. It’s a shrewd metaphor that seconds Roach’s intimation of the impossibility of knowing the full truth about our families.

Every family habitually conceals its secret pain by developing unspoken rules. For Roxana Alger Geffen, a Washington artist with WASP roots, objects found in her family’s attic and her grandmother’s junk drawer were the starting point for “The Binding Ties.” Employing these materials in unexpected combinations, she created a comical but telling series of sculptures that explore personal identity within the tacit expectations of the family. Illustrating the proper interests of a perfect father figure, “The Robe of Rote Masculinity” resembles an elegant dressing gown, but it is stitched from fabric printed with images of a golfer practicing his swing and its hem is weighted with a row of old wrenches. The robe’s well-tempered mate shows up in “The Genteel Role of Feminine Blindness,” featuring a life-size, immaculately white figure with tassels dangling where its eyes should be above a dress fashioned from embroidered dish towels and trimmed with hundreds of the annoying plastic tabs used to attach price tags. One can easily imagine polite conversations at the dinner table where no one would dare to rock the boat, let alone reveal personal passions or gnawing woes.

A common theme throughout this show is that from photos to attic clutter, every object has strings of meaning attached. Whether these are joyful, nourishing or painful, they are almost always poignant in their fragmentary nature. By rifling through his family’s old photos and documents, Aaron Wax, of Brooklyn, was able to create a halting reconstruction of his grandfather’s arrival in America, including a passport-like photo of his grandfather, stamped with official-looking seals, that shows him neatly dressed in a suit and tie with an anxious, faraway look in his youthful eyes. A Polish Jew who tragically lost his first family in World War II, his identity has been reduced to a few teasing artifacts that sketch his story but tell little of the man himself. Wax never knew his grandfather, but as he notes in some explanatory text on the wall, “If not for his great loss I would not be alive.” In this thought, he acknowledges that family not only shapes identity, but is, on the most basic level, the material reason for one’s existence.

Immigration is a vexed topic these days with effects that resound down through the generations. For Washington artist Khánk H. Lê, whose family brought him to America from Vietnam when he was a small child, immigration and its consequences are immediate and ever-present. Encrusted with patterns of rhinestones and glitter, his images are as instantly alluring as a display in a candy store yet so unremittingly busy that they are almost hard to look at. Like Roach, Lê began with family photos that offer glimpses of tenderness and mutual support. Reproducing them as stark, high-contrast paintings, he spotlights each family member or group by positioning them in an alien world of flat, shimmering patterning. Contrasted with these chilly stand-ins for the jazzy, jittery hyperactivity of contemporary American culture, their humanity and vulnerability take center stage.

There is arguably no stronger influence on personal identity than the family, whatever its history. Whether considering the stories evoked by this exhibit or tracing our own family’s examples, we find threads that lead in countless directions. However much we can discern the connections they make, there are multitudes more lost to memory and time that nonetheless exert profound effects on our character and understanding. These are the mysteries that shape us as individuals, as families and as a culture. Look deeply enough and we find the whole world is our influence.

Mary McCoy is an artist and writer who has the good fortune to live beside an old steamboat wharf on the Chester River. She is a former art critic for the Washington Post and several art publications. She enjoys the kayaking the river and walking her family farm where she collects ideas and materials for the environmental art she creates, often in collaboration with her husband Howard. They have exhibited their work in the U.S., Ireland, Wales and New Zealand.