Human life has been on a near-universal lockdown since the coronavirus pandemic first gripped the country in late March. It has been a crushing blow to the economy, but another sector has reaped a windfall: the environment.

Power plants eased off electricity production. People stayed home more, and many cars disappeared from the roads. As a result, air pollution is down sharply, and new records are being set for air quality across the Chesapeake Bay region.

Researchers are normally cautious about ascribing an observed phenomenon to a specific cause so soon. But many say the current situation is unique.

“We’ve seen this immense decrease in passenger traffic, anywhere from 40–50% depending on where you are in the state,” said Jeremy Hoffman, chief scientist at the Science Museum of Virginia. It’s important to note that weather plays a huge role in air quality, he added, but “that huge drop in traffic coinciding with this huge drop in [nitrogen dioxide] in the air is, to me, a pretty convincing relationship.”

Nitrogen dioxide, or NO2, is emitted by cars, trucks, power plants and anything else that burns fossil fuel. Fuel combustion also is a major driver of ozone and particulate pollution.

Where such air pollution levels are consistently high, people can suffer from asthma and an increased risk of developing respiratory infections, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Emerging research has shown that areas with poor air quality have higher death rates from COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

Air pollution also makes it more difficult to clean up the Chesapeake Bay. The state-federal Chesapeake Bay Program estimates that air pollution contributes about one-third of the nitrogen found in the Bay, fueling algae blooms that kill aquatic life.

Emissions of nitrogen oxides and other fuel-related pollutants have shrunk significantly over the past two decades. But scientists say they’ve rarely seen anything like the plunge in recent weeks.

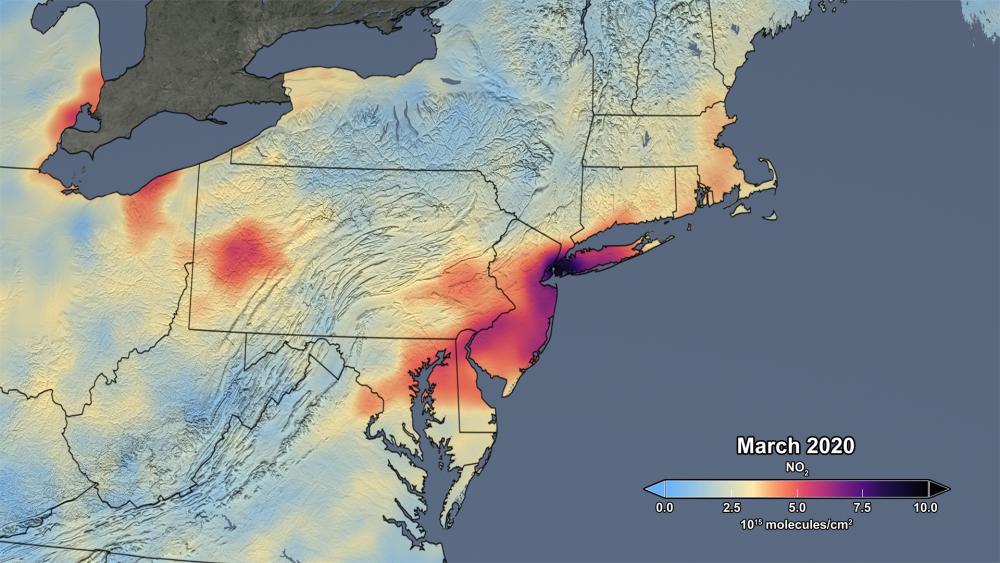

The average amount of air pollution from nitrogen dioxide in March 2020, while travel — and the related burning of fossil fuels — was greatly reduced to address the outbreak of COVID-19. (NASA GSFC)

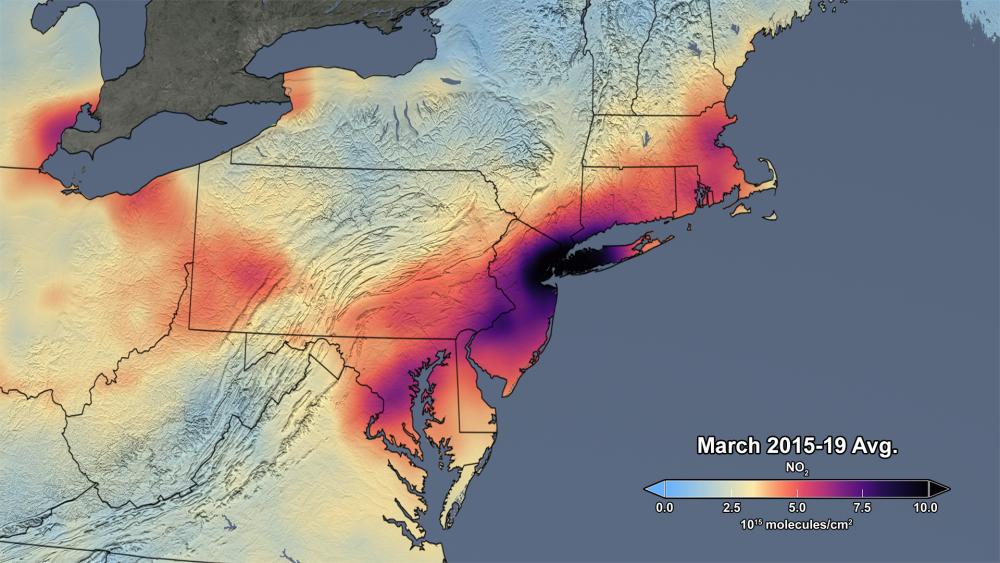

The average amount of air pollution from nitrogen dioxide during the month of March 2015-2019. Nitrogen dioxide gets into the air mostly from the burning of fossil fuels. (NASA GSFC)

Researchers at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in Greenbelt, MD, have been tracking atmospheric dioxide since 2005, using the agency’s Aura satellite. This team’s analysis shows that March of 2020 set a record for the lowest levels of the pollutant in that month during 20 years of tracking. The amount was 30% lower than the typical March reading from 2015–19 along the Interstate 95 corridor from Washington, DC, to Boston.

Air pollution has been trending downward for years, “but this is a step-change down because of the emissions reductions we’re seeing now,” said Ryan Stauffer, a NASA research scientist who studies the atmosphere. “This is like a grand, unintended experiment in atmospheric chemistry.”

Stauffer cautions that the month’s rainy and windy weather likely lent a hand in reducing pollution levels; rain droplets attract aerosol particles as they plummet to the ground, leaving cleaner air behind. And the satellite can only measure air quality throughout entire columns of the atmosphere, so ground-level pollution, which is more likely to be generated by humans, is only part of the picture produced by the satellite.

Ground-level sensors are telling a similar story. The DC metro area has seen a string of healthy air days dating back to March 20, according to EPA monitors that detect ozone and particulate matter. As of May 3, that was 45 days and counting, shattering the region’s previous record of 22 consecutive days, Stauffer said.

Scientists don’t expect the air quality gains to be permanent. When the lockdown is lifted and fuel combustion kicks back into gear, pollution levels are likely to zoom back to pre-pandemic intensity, they say.

The event could help shed more light on how reductions in air pollution affect human health.

In one of the most cited cases in the field, researchers detected a 30% drop in ozone levels when Atlanta all but halted traffic during the 1996 Summer Olympics. Although research initially suggested fewer asthma attacks happened during the games, a follow-up study revealed no firm connections to that or other respiratory ailments, perhaps because there were too few emergency department visits to support the theory.

China’s crackdown on traffic and industrial pollution during its 2008 Summer Olympics also provided a window into the phenomenon. Scientists have variously described a reduction in premature deaths, improved cardiovascular health and higher birth weights.

But more research is needed to firm up the scientific community’s understanding of health effects, Stauffer said. He and fellow researchers have been fanning out across the DC area during the pandemic, collecting air samples in silver canisters. By studying various emission levels, the team hopes to learn whether the short-term air improvements influence pollution levels after the quarantine is lifted.

“This is not the way we want to be cutting air quality problems or reducing pollution,” Stauffer said. “Any reductions we see from the air quality will be temporary. Any impacts we see in the environment or human health, that’s yet to be seen.”

By Jeremy Cox