For seven months I have been living with the medical possibility I might not be here this Thanksgiving. I’m happy to announce that I am here and had what Mr. Rogers described as “a wonderful day in the neighborhood.” It was just the two of us, Jo and me.

Showing up is the first order of business for just about anything. It felt good to show up, or more succinctly, to be able to show up.

We put together the most un-pilgrim like Thanksgiving imaginable. Our goal, since this Thanksgiving was so unique––I’d describe it as a ‘freebee’ ––- was to arrange the day so as to make for good eating but be as effortless as possible since none of the kids would be here to help. Cooking turkeys, albeit a hallowed rite of any American Thanksgiving, I think is a pain.

We bought two huge fillet mignons. We may have just as well put up our mortgage such was their cost, but this was an auspicious occasion. We had Graul’s prepared potatoes, string bean casserole and other typical Thanksgiving viands left over from the prior Sunday before Thanksgiving. Then, my son, Craig, and his wife, Brenda, had been with us for dinner. It was precious time.

On Thanksgiving Day, we grilled the fillets, reheated leftovers and we enjoyed an elegant and no hassle dinner. We wanted to be as available to each other and not tied to the kitchen. The fillets were so tender they became virtually soluble with only the slightest pressure from our forks.

It’s a risky business buying store-bought apple pie. A store-bought pie can be like purchasing a Rolex from a vendor on a city street corner. What you sees is not what you gets. The pie was displayed well in a clear plastic container, in the way jeweler’s present their choice diamonds in glass casings. I was amazed but the pie was “of the first water” as jewelers call their best diamonds. It tasted just fine, much cheaper than diamonds and far less than the fillets.

Popping a piece of pie in the microwave for forty seconds, then daubing either vanilla ice cream or whipped cream on top, the pie was awesomely delectable and when I had my first forkful I felt as if I had died and gone to heaven, not a metaphor I use lightly these days.

During the day we made and received calls from various kids and kin. We held a Zoom conversation with one of our families and told stories. Each year I tell a Thanksgiving favorite about my confrontation with two monstrous turkeys while walking in my driveway. “Five feet tall, no less, I tell them.” The grandchildren, of course know I’m full of it, but they think it’s a hoot to have Peepa, as I’m called, recite this challenging moment of my life. They shake their heads incredulously, check cell phones, and for a moment look as if they almost believe it but soon roll their eyes and groan as if in pain. They giggle, too.

Thanksgiving is the time of recollection when we celebrate the day but also recall significant moments of our past. The day often turns out to be a confluence of our past, present and future.

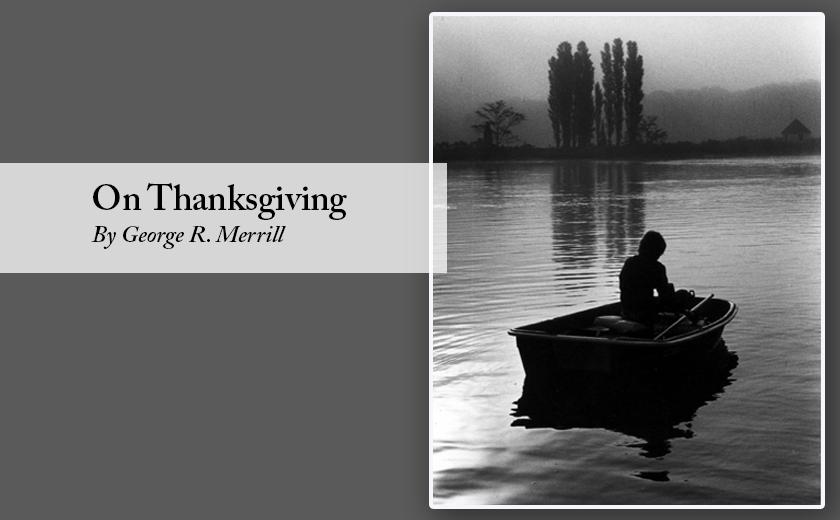

As I grew older, I gave up sailing, a lifelong love. It required too much of me. When I was first taken ill seven months ago, I had little energy to do other things I loved doing before. Fortunately writing was sedentary and I soon got back to it. Gradually my energy returned.

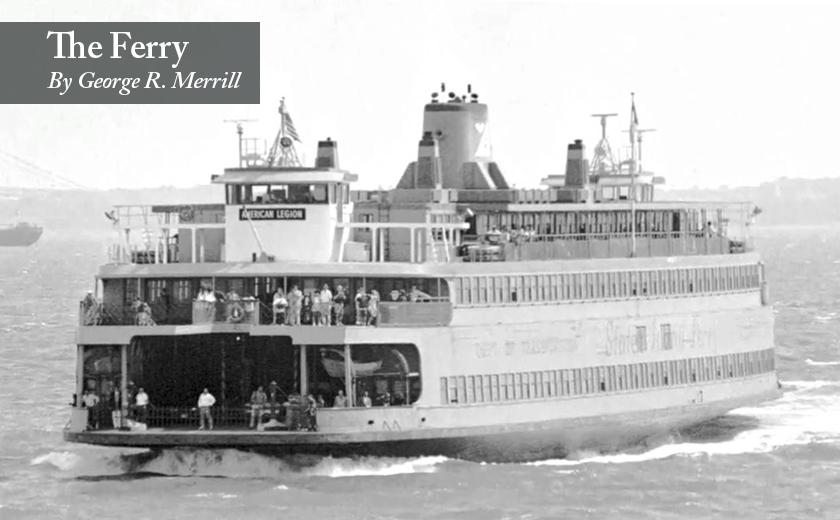

I’d been active in doing darkroom photography for most of my life. I loved everything about it, as I did writing. My energy suffered and I abandoned photography for a while. Then, on this last Thanksgiving Day, I decided it was time to return to the darkroom again and print photographs. I’d been thinking of one negative I was especially fond of. The printed photograph of it appears above in the essay.

I wondered why this particular one? I had hundreds of others I also liked.

My son, Craig, never enjoyed sailing much but preferred sports. When he was young didn’t sail with me, anxious that he might miss practices or games. I understood this but had always wished that he and I might share this particular love of mine. He surprised me one day and asked if I would take him and his friend for an overnight on the boat. I was thrilled. We planned the trip. I knew that bringing a friend sweetened the pot for him, and even though it might ‘dilute’ that special time I’d always wanted with him, I’d happily take what I could get.

We sailed from Middle River to Fairlee Creek here on the Shore and anchored for the night. We swam off the boat, cooked on the galley stove and slept under the stars. In the early morning while the mist was still suspended over the water, we weighed anchor to sail back to Middle River on a gentle southerly breeze. He obviously had fun as did his friend. I was ecstatic. I also knew this excursion would probably be the last. He was a passionate athlete, deeply invested in sports and was being pulled more and more in that direction.

I suspected there was some kind of a subtle resonance between how I felt on this the wonderfully satisfying Thanksgiving Jo and I were having, and the photograph I was printing that documented the adventure I once enjoyed with my son years ago. The sail with Craig was the last one we made together. Would this Thanksgiving also be the last for Jo and me?

For us, Thanksgiving Day had an undertone of melancholy which reflected a sense that we knew that our lives as we’d known them were being conditioned by a deadline.

This undercurrent went unspoken, but the sense of a finality was there. The pleasures of the day kept such dark musings sufficiently distant so I can say ––– and I know Jo would –– that it was a beautiful day in the neighborhood.

I know perfectly well that everything that ‘is,’ is impermanent. I cannot seem to get my heart on the same page as my head. Best to live Thanksgiving Day as just that, Thanksgiving Day. There is a time for everything under the sun including a time for just showing up and being thankful for having shown up.

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.