As I view student protests at an increasing number of colleges and universities, I disdain the disruption but respect free speech. I feel conflicted.

When I ponder the dysfunction in Washington, D.C. and extreme difficulty recently in passing legislation to support Ukraine and Israel, I can see reasons for voting for and, not easily, against the appropriation.

The upcoming presidential election puts two vastly different politicians and people against each other, one whom I despise, and one whom I like, but not enthusiastically.

What’s my point?

In our highly polarized nation, it seems that our opinions are irreversible, with little allowance for accepting opposite points of view. I am guilty too. I must strain to appreciate the reasoning behind immovable right-wing political positions.

I must refrain from demonizing those who disagree with me.

After recently reading an op-ed written by the New York Times writer, Frank Bruni, I realized that “humility” is missing in our “I’m right, you’re wrong “culture. Each of us is moored to our perspectives.

We refuse to budge.

Bruni opines that getting stuck in mental concrete, unwilling to appreciate polar-opposite viewpoints, promotes lack of civility and potential violence.

Bruni wrote, “We live in an era defined and overwhelmed by grievance—by too many Americans’ obsession with how they’re wronged and their insistence on wallowing in ire. This anger reflects a pessimism that previous generations didn’t feel.

The ascent of identity politics and the influence of social media, it turns out, was better at inflaming rather than uniting us. They provide a self-obsession at odds with community, civility, comity and compromise. It’s a problem of humility.”

Were I a student at Columbia University or Yale or Brown or Penn or New York University or University of Texas at Austin or Emerson or Emory or the University of Southern California, among others, I would be darn mad that encampments block my way to classes and a degree. On the other hand, I would have to force myself to understand that the single-minded, pro-Palestinian protesters feel disrespected or, at least, ignored by administrators.

However, the antisemitic message riles me. I feel angry and disappointed.

The police presence often exacerbates a provocative stand-off. At the same time, being arrested is a badge of honor for students, simply the price of protesting.

Preternaturally unable to understand why right-wing members of Congress opposed vital aid to the beleaguered Ukraine and oft-disparaged Israel, I must acknowledge a long-established strain of isolationism in our country. Some also must think that Ukraine’s President Vladimir Zelensky is fighting a lost cause against Russia’s overwhelming military advantage.

I believe that Russia cannot be allowed to assume control over an independent nation. If allowed to invade without opposition, the Russians will feel emboldened to attack the Baltics and other border states.

And the upcoming presidential election pitting the 81-year-old President Joe Biden against the 77-year-old former President Donald Trump is rife with conflict, contrast and contention. The Biden White House runs on reason and rationality and the other on chaos and corruption.

While nothing about Trump pleases me, I must understand that his fervent supporters like his outspoken and anti-establishment public posture. They ignore his self-obsession. They like his policies.

Bruni wrote, “While grievance blows our concerns out of proportion, humility puts them in perspective. While grievance reduces those with whom we disagree to caricature, humility acknowledges that they’re every bit as complex as we are—with as much a stake in creating a more perfect union.”

Humility requires a mindset to accept the thinking and passion of the “other side.” I am not suggesting agreement, but a smidgeon of emotional and intellectual restraint.

Anger and recrimination only poison dialogue, dividing us with different opinions even further and creating a bitterly wider schism.

Neither Bruni nor I foresee a wholesale change in American attitudes toward disagreement. But perhaps we can take a healthier approach in our minute corner of the universe.

Humility breeds civility, which in turn spawns a sense of compromise and reasonableness.

Columnist Howard Freedlander retired in 2011 as Deputy State Treasurer of the State of Maryland. Previously, he was the executive officer of the Maryland National Guard. He also served as community editor for Chesapeake Publishing, lastly at the Queen Anne’s Record-Observer. After 44 years in Easton, Howard and his wife, Liz, moved in November 2020 to Annapolis, where they live with Toby, a King Charles Cavalier Spaniel who has no regal bearing, just a mellow, enticing disposition.

One event represented a divided country, resulting in the bloodiest one-day battle ever carried out on American terrain. This Civil War action had favorable consequences for the Union cause based upon a pivotal decision by President Lincoln.

One event represented a divided country, resulting in the bloodiest one-day battle ever carried out on American terrain. This Civil War action had favorable consequences for the Union cause based upon a pivotal decision by President Lincoln.

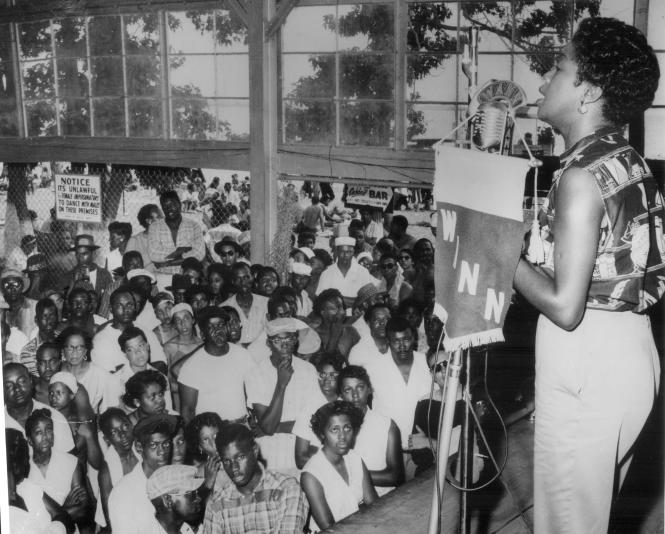

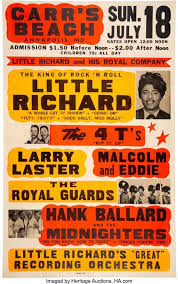

The ugly past in the neighborhood where my wife and I live in Annapolis jostled my sensibilities. Like many White folks, I understood that the present and future were free in many ways from the miserable restrictions imposed on Blacks, so common to life in America,

The ugly past in the neighborhood where my wife and I live in Annapolis jostled my sensibilities. Like many White folks, I understood that the present and future were free in many ways from the miserable restrictions imposed on Blacks, so common to life in America,