This is a story about an opportunity to spread the word about Blacks of the Chesapeake. Up to recently, that story went untold or ignored. Segregation forced resilience and resentment upon African Americans excluded from equal opportunity due to their skin color.

In the fall of 2022, the door to a wonderful musical history created by an enterprising Black Baltimore businessperson opened for residents of the Chesapeake Bay region to learn and appreciate. “Wow” would be the right reaction, as it was for me and continues to be.

The ugly past in the neighborhood where my wife and I live in Annapolis jostled my sensibilities. Like many White folks, I understood that the present and future were free in many ways from the miserable restrictions imposed on Blacks, so common to life in America,

The ugly past in the neighborhood where my wife and I live in Annapolis jostled my sensibilities. Like many White folks, I understood that the present and future were free in many ways from the miserable restrictions imposed on Blacks, so common to life in America,

As I have previously written, Carr’s and Sparrow’s beaches fronting the Chesapeake Bay provided a recreational respite for Black families from Baltimore, Philadelphia and Washington, DC. in the 1940s through the early 1960s. They could go nowhere else. They confronted limited options to relax and recreate.

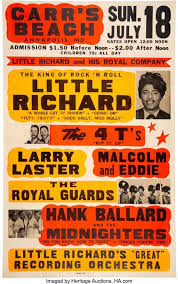

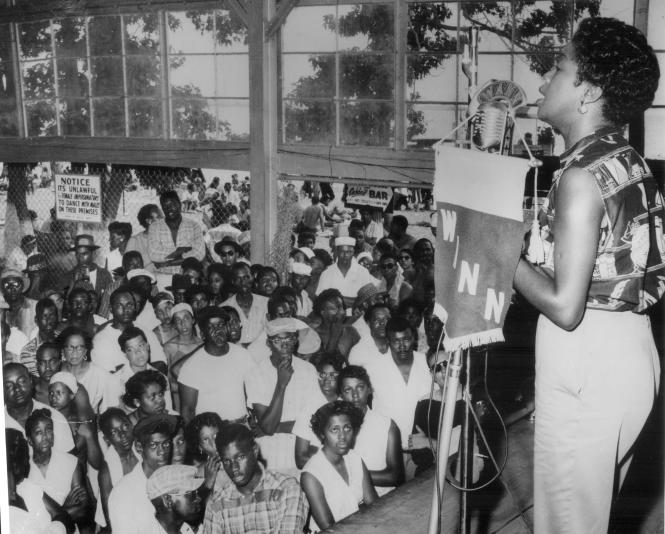

Thanks to the enterprising Willie “Little Willie” Adams, who parlayed a fortune fueled by controlling the illegal numbers racket in Baltimore (now the State Lottery) into legitimate businesses, bought 180 acres in 1948–including Carr’s, Sparrow and Elktonia beaches on the Annapolis Peninsula. He then developed a renowned summer musical venue that drew super-talented artists like James Brown, Ella Fitzgerald, Stevie Wonder, Cab Calloway, the Temptations, Ike and Tina, the Shirelles, Little Richard, the Drifters and Billie Holliday.

The sounds of these incredible performers permeated my adolescence.

When I visited a good friend at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Va. during my college years, I watched the unforgettable and incomparable James Brown, the “King of Soul.” I was mesmerized. Brown thrilled audiences with his physical energy and vocal talent.

Until congressional enactment of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, Carr’s Beach throbbed on summer Sunday evenings with dance-till-you-drop music. The performers could not perform in Whites-only locations on the East Coast.

Jim Crow discrimination placed awful obstacles in front of African American athletes, performers, businesspersons, educators, doctors, and nurses. Fortunately, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 brought change. Carr’s Beach musicians took their musical gifts to venues formerly closed to them.

The Annapolis Peninsula became a quiet residential community.

Carr’s and Sparrow beaches are now the sites of, respectively, of a large and expensive apartment complex and an Anne Arundel County sewage treatment plant. The BayWoods of Annapolis retirement community, where, as readers know, my wife and I live, sits on part of Elktonia Beach.

Musical artistry is in the past. But history has staying power.

Within the past few years, a five-acre parcel on Elktonia/Carr’s Beach was saved from forty-three townhomes and converted into the Annapolis Heritage Park. Recently the Moore Property, overlooking the Bay on Elktonia Beach, was purchased by the city for use eventually as the headquarters of Blacks of the Chesapeake Foundation, a nonprofit focused on telling unknown and unheralded stories about Black residents of the eastern and western shores.

The Moore parcel, which includes a now dilapidated cottage, was owned by the late Dr. Paulett Moore, the second president of Coppin State University. Its new use will provide an educational purpose as a visitors center.

Annapolis Peninsula contains two upscale boatyards and middle-income housing. It is difficult but not impossible to envision the popularity of Bay front beaches and world-class music. The dreadful days of Jim Crow discrimination are gone but not forgotten.

Little Willie Adams was a widely known entrepreneur in Maryland. He also was something else: a social visionary who offered opportunity for family recreation and musical artistry that transformed the lives of African American visitors.

I likely would not have felt welcomed on Carr’s and Sparrow’s beaches. Nonetheless, I find the history pleasurable to know and understand. Progress happens slowly.

Columnist Howard Freedlander retired in 2011 as Deputy State Treasurer of the State of Maryland. Previously, he was the executive officer of the Maryland National Guard. He also served as community editor for Chesapeake Publishing, lastly at the Queen Anne’s Record-Observer. After 44 years in Easton, Howard and his wife, Liz, moved in November 2020 to Annapolis, where they live with Toby, a King Charles Cavalier Spaniel who has no regal bearing, just a mellow, enticing disposition.

lance bendann says

Well done, Howard, as usual. I enjoy your columns every week and now this one in particular. Your reminiscences brought back some very vivid memories of the musical life of my youth, not to mention it pieced together interesting information and commentary on those musical, but often turbulent, years. Growing up in Baltimore I was very much aware of Willie “Little Willie” Adams. Who wasn’t? He had a way of getting his name in the paper it seemed every day. Your comment that Mr. Adams “parlayed a fortune, fueled by controlling the illegal numbers racket in Baltimore “, and then adding parenthetically in reference to the illegal numbers racket…… “(now the State Lottery)”…… cracked me up!

Frank Mickey says

A wonderful view of a checkered but treasured part of all our Past. While in D.C. at grad school, I visited a bar for recorded jazz and found myself the only white face (once my eyes adjusted). I ordered and drank the fastest beer ever and then left, but gained an indelible appreciation for the power of exclusion, even if not overt. Your article glows in my mind – thanks!