An autumn morning. The sun burns up the eastern horizon to dissolve the scarf of fog draped across the Choptank River. The crunch of frost as two men walk along the shore of riprap and river weed, their break-open shotguns cradled across their forearms. They drift from hunting pheasant to talking about the Phillies’ last-place losing season, then speak in lower octaves about Soviet leader Khrushchev’s “secret speech” denouncing Stalinism to a closed session Communist Party Congress three years before.

Ashford Farm, a CIA “safe house” used for debriefing Russian and Eastern bloc defectors. Its cover was blown in 1962 when news reporters picked up on a rumor that Francis Gary Powers was there.

One man is a Russian naval officer recently defected to the West, the other is an ex-major league pitcher and now the Director of the CIA’s Alien Branch, a “safe house” at Ashford Farms, a Tudor-style mansion in Talbot County’s Royal Oak, just west of Easton. It is 1959, the height of the Cold War, and Nicholas Shadrin and Pete Sivess have become friends after the many debriefing sessions that provided the CIA with valuable information about the Russian Navy. They would remain friends for another 15 years.

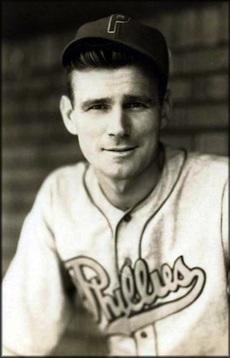

Sivess was born to a Russian-speaking Lithuanian family in New Jersey. A natural athlete, he excelled in high school baseball (1932 All-State) and went on to Dickinson College, where he set the record for strikeouts—243 by the end of his senior year. Scouted and signed by the Philadelphia Phillies, he was placed on the roster right away. They say he had a blazing fastball and was billed as the next “Dizzy Dean.” Unfortunately, his offseason job as a stevedore began to take a toll on his arm, and he was traded around in the majors until he landed in Baltimore with the Orioles where, after changing his pitching technique to sidearm, had one of his better seasons. After a few more trades and an impending war, Sivess left baseball for good, worked for a Grumman Aircraft in 1942, and a year later joined the Navy.

Working for the chief of naval operations, Sivess was assigned to help train the Russian Navy, our allies during the war. He would continue his service by working in Romania and Czechoslovakia, developing a perfect resume for the CIA. He joined them in 1948, one year after the Agency’s inception. Three years later he was in Easton, designing a program to help debrief eastern bloc defectors. Sivess retired to St. Michaels in 1972. According to Jack Morris, in an article for the Society of American Baseball Research, Sivess granted an interview to the Baltimore News-American in 1984. Circumspect about his time in the clandestine service, Sivess preferred to talk baseball, closing with “I always thought I was every bit as good as the players I was facing,” said Sivess. “But I honestly wasn’t enamored with baseball. That’s just the way I am. The game was just a phase of my life.”

Nicholas Shadrin walked a more fateful path. One of the most valuable defectors of the time, Shadrin and his soon to be wife Ewa, a Pole, whose family’s anti-communist leanings would block any future marriage, defected to the West in a daring sea escape to Sweden, then through a network of countries to the US and eventually his debriefing in Easton. His information was “worth its weight in gold,” and for his cooperation, both he and Ewa were rewarded with education opportunities. Shadrin completed his Master’s Degree and Ph.D. in engineering. Ewa, whose training was underwritten by the CIA, became a dentist.

In the mid-60s, Shadrin was contacted by the KGB and was supposedly blessed by the CIA to work in counter-espionage. But soon, his value was depleted, and his jobs for the Agency became more mundane. Until 1975. Contacted again by the KGB, the CIA and FBI wanted to run Shadrin as a double-agent. Various sources point at US intelligence agencies for advocating the perilous arrangement. Shadrin had already been outed during an open Congressional committee meeting, but the CIA-FBI still felt they could exploit the opportunity presented with the KGB contacts. His second meeting with the KGB was the last time he was seen.

Some years later, after his wife sued and pled with the government for information about her missing husband, KGB Major General Oleg D. Kolug told US intelligence that Shadrin had died of a heart attack during the kidnapping. Others say he died from chloroform used during his abduction. A public 1985 CIA document stated that Shadrin had been tried by Russia in-absentia and that the Vienna trip (ostensibly to help cover a highly placed Soviet spy) was, in fact, an elaborate KGB scheme to catch him. The CIA report states that he was executed the same day he was kidnapped. Letters to President Jimmy Carter and to Senator Alan Cranston from (author redacted)—probably Ewa Shadrin’s wife—are posted on the CIA website here.

Pete Sivess lost a good friend, and the Agency lost a man who risked everything for his adopted country.

Many other defectors would be debriefed in the safe house, most famously, Francis Gary Powers, the U2 pilot shot down over Russia in 1959. The prisoner exchange—Powers and US student Frederic Prior for KGB Rudolph Abel—was dramatized in the 2015 historical drama, “Bridge of Spies.”

The house at Royal Oak still stands and has been on and off the market for years.

Part Two begins next week.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.