Constantino Brumidi (1805-1880) was born in Rome of Italian-Greek parents. A promising young artist, he was admitted as a student to the Academy of Arts in Rome when he was thirteen years old. At the Academy he learned to paint in the Classical manner. His successful career in Italy included many portrait commissions, and when Brumidi was thirty-five, Pope Gregory VI commissioned him to restore Raphael’s frescoes in the Vatican Loggia. Brumidi was a captain in the National Guard fighting on the side of Pope Pius IX against the Republic in the Roman Republic revolt of 1849. He was imprisoned for fourteen months. When the revolt ended and Pius IX regained his position, he was able to get Brumidi released from prison. However, Brumidi’s release was conditioned on his leaving Italy. The family left Italy in 1849 and reached New York in 1852. Brumidi painted altarpieces and portraits in New York City, Mexico, Philadelphia, and Maryland until he went to Washington, D.C. in 1854.

In 1856, Brumidi met Captain Montgomery Meigs of the Army Corps of Engineers. Meigs was supervising the construction of buildings in the Capital. Meigs commissioned Brumidi to paint a mural in the meeting room of the House Committee on Agriculture. He was paid eight dollars per day until Jefferson Davis, then Secretary of War, saw the work and had Brumidi’s salary increased to $10. Brumidi’s mural was admired by everyone, and he became the painter of the Capitol.

“Apotheosis of Washington” (1865) (4,664 square feet) (180 feet above the floor) was commissioned by the Senate to be placed in the rotunda of the Capitol. Washington died in 1799, and by 1800 a commemorative print showing him ascending into heaven was popular. A statue of Washington by Horatio Greenough was commissioned by the Senate (1832) to be place in the Capitol. Unfortunately, Greenough depicted Washington seated on a throne and dressed in a Roman toga, his chest bare. The sculpture and Greenough were severely criticized, and the sculpture was removed. Brumidi did not wish to share the same fate. His Washington wears a military uniform.

Brumidi’s design was influenced by the Italian Renaissance artist Antonio da Correggio, who pioneered painting a domed ceiling with his “Assumption of the Virgin” (1522) in the Cathedral of Parma, Italy. Brumidi’s composition is essentially two circles within the dome. The center circle contains Washington, Liberty, Freedom, and thirteen young women representing the thirteen colonies. The outer circle of the dome contains the six major strengths of America: Agriculture, Mechanics, Commerce, Marine, Science, and War.

Brumidi painted all his murals in the Capitol in true fresco, a technique he introduced to the Capitol. True fresco involves painting on a freshly plastered section of wall, allowing the color to penetrate the plaster and become part of the wall.

The term apotheosis refers to the entrance into heaven of an individual, considered equal to the gods and therefore divine. Washington was not deified by the U.S. Senate, but he was considered to be the Father of the Country and guardian spirit of the United States. Dressed in a blue military uniform with gold epaulets, Washington holds his sword, point downward, in his left hand, and he gestures with his right hand extended toward Liberty. Liberty, a young blond woman, wears a peaked red cap, the “red cap of liberty” worn in the French Revolution. She carries Roman fasces, a bundle of rods tied together by a cord with an axe head projecting from the top. It was the Roman symbol of civil authority, and it became the symbol of American democracy, of unity and of strength. One rod breaks easily but together they are strong. Winged Victory sits at the other side of Washington. She carries the palm branch of peace and wears a laurel wreath crown of victory. She blows a victory trumpet. The depiction of these three figures sitting atop the rainbow is a reference to Genesis story about the flood and God’s covenant with humankind.

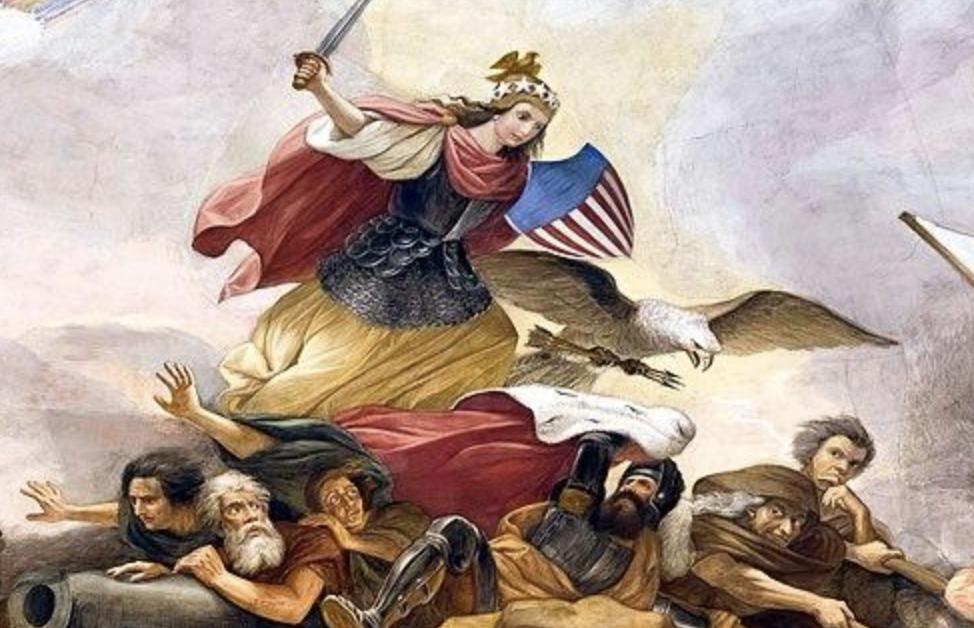

Below Washington, War is represented by the figure of Freedom and an American eagle. Freedom, also known as Columbia, derived from the name of Christopher Columbus, is clothed in red, white, and gold, and wearing armor. She wields a sword and shield, and wears a gold helmet with white stars and golden eagle. She fights five male figures who represent tyranny and the power of kings. The central figure, representing royalty, wears a full set of armor and a red cloak with an ermine lining. He falls to the ground, his golden scepter and symbol of his power falls with him. At his right, three figures, one young, one middle aged, and one old look fearfully at Freedom and fall to the ground on top of a cannon. Two menacing male figures at her left, one an old man holding two flaming torches, fall to the ground.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

American agriculture is represented by the Roman goddesses Ceres and Flora. Ceres represents the sowing, nourishing, and harvesting of all agricultural products. Sitting among shafts of wheat, Ceres wears a crown of wheat and holds a cornucopia full of vegetables, a pineapple at the top. A male figure dressed in gold wears the red cap of liberty, which America enjoys. He hands Ceres the reins of two palomino horses that pull the McCormick reaper, the frame and wheel partially visible. Flora, the goddess of flowering plants, gathers a bouquet.

The mechanical advancements of America are represented by Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and the forge. He was inventor of smithing and metal working that provided Rome with its superior weapons. Vulcan stands with is right leg resting upon the barrel of a cannon. He can be identified by his hammer and anvil. Two figures at his right lift a metal fasces. Behind them smoke rises from the stack of a steam locomotive.

Mercury, the Roman god of commerce, finance, and messenger of the gods, sits upon boxes and crates. He wears winged sandals and a winged hat, and he carries a caduceus. At his right, men shift boxes on a dolly. Mercury hands a bag of money to Robert Morris, the gentleman in the dark blue suit and powdered wig. Morris was a major financier of the American revolution. At his feet, an anchor points toward the ocean and to the next scene. Smoke arises from two chimney stacks visible in the distance.

Several of the young women who represent the thirteen colonies sit on the ring of clouds above Commerce. They hold a banner with the words E PLURIBUS UNUM.

Representing the oceans and marine life is the Roman god Neptune, holding his trident. His seashell chariot is drawn over the waves by two white seahorses, and he is accompanied by mermen and an infant on a dolphin. Venus, draped in blue, holds onto a black cable, representing the transatlantic cable that was being laid at the time.

The rainbow on which Washington, Liberty, and Freedom sit, connects the two paintings of Science and Agriculture. Minerva (Greek Athena), Roman goddess of wisdom, justice, law, arts, and victory in war, holds a spear and wears a warrior’s helmet. She points to the three men sitting beside her: the inventors Benjamin Franklin, Samuel F. B. Morse, and Robert Fulton. The two male figures in front of them look at an electric generator and a printing press. To her right, a group of students listen, discuss, and write. Kneeling on the ground, the figure in brown may reference Euclid from Raphael’s “School of Athens.”

Brumidi continued to paint in the Capitol until his death. He collapsed while working on a scaffold 58 feet above the floor. He was able to hold onto the scaffold until rescue came. A few months later he died (1880). In his eulogy for Brumidi, Senator Justin Morrill of Vermont stated, “So long has Brumidi devoted his heart and strength to this Capitol that his love and reverence for it is not surpassed by even that of Michelangelo for St. Peter’s.”

Brumidi was buried in an unmarked grave in Glenwood Cemetery in Washington, D.C. The location of his grave was lost until it was rediscovered in February 19, 1952. A marker was placed there. In 2008, Brumidi was awarded posthumously the Congressional Medal of Honor.

“My one ambition is that I may live long enough to make beautiful the Capitol of the one country on earth in which there is liberty.” (Constantino Brumidi)

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.