Jacques Louis David lived and worked in interesting times in Paris. In 1748, the year of his birth, archeologists discovered the ancient Roman ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum that initiated a new interest in everything Greco-Roman. In 1775, the well known German historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann published Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Art, a must reading at the time. In 1776, the American Revolution, aided by the French, came to a victorious conclusion. Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette ruled France from 1793 until the French Revolution in 1789, and Napoleon Bonaparte arrived on the scene from 1799 until 1814. These historical events were consistently intertwined with the life and art of David.

As a young man David was taught by well known and respected Parisian artists. He enrolled in the Royal Academy in 1766. He was talented and ambitious. His student paintings were accepted into the juried Academy Salons. He won the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1775; entitling him to live, learn, and work in Rome at the expense of the Academy. Having decided precisely what he wanted to get out of the experience and what he thought it was important to paint, he wrote, “The art of antiquity will not seduce me, for it lacks liveliness.” He was young and he was wrong. After visiting Herculaneum, the Greek temple at Paestum and the Pompeii frescoes in Naples, he was hooked. He later said he felt as if he had just been “operated on for cataract of the eye.”

He embarked on a series of paintings inspired by ancient Greek and Roman texts. David’s breakthrough painting was the very large “Oath of the Horatii” (1784-85) (10’8’’ x 14’). With this painting he is credited to have initiated a new artistic style heralded as Neo-Classicism. The “Oath of the Horatii,” first exhibited in his Roman studio and then in Paris, caused a sensation. David became the equivalent of a pop star. This new style signaled the end of the fantasy, frivolous, and excessively pastel Rococo style of Louis XV and Louis XVI. Instead of lush pastel fabrics laden with bows and laces, David’s figures were dressed in plain Roman togas in strong reds and blues. The Rococo’s endless fluffy green gardens with frolicking cherubs and feathery landscapes were replaced by grey stone columns supporting three Roman arches that enclose the scene. A strong light source from the left highlights three groups of figures in the front of the composition and casts the arched background in dark shadow. Everything is solid, steady, and clearly defined.

The inspiration for the painting came initially from a recent French tragedy about ancient Rome by Corneille, but was itself derived from the Roman historian Livy’s book From the Founding of the City, that covered the period of 753 BCE to Augustus in 14 CE. A war between the city of Rome and the neighboring city of Alba Longa was going to be fought, however, it was decided not to fight a battle between the two armies, but between the three sons of the Horatii representing Rome and the three sons of the Curatii of Alba Longa. Many lives would be saved as a result. Centered in the painting is the father of the Horatii who stands in a stable triangular pose and holds up the swords of his three sons. They raise their arms and pledge their lives to fight and die for Rome. The sons are fully dressed in armor and are placed side by side in a strong triangle configuration. These two groups are each placed in front of a dark background arch. The light shines on the son’s backs, casting their fronts and faces in shadow, but their arms in pledge are well lighted as they reach upward to their swords. Symbolically, the three swords in their father’s hands are the central focus of the composition, not the sons or the father.

The third grouping in the composition is composed of the mother, daughters, wives, and children of the men. Their poses sink lower than the men and are composed in soft curves, rather than straight lines. They weep for their men. David has placed them in accordance with the thinking of the time. The men are in strong light, standing in straight line poses representing their courage, intelligence, patriotism, and reason. They know where their duty lies, even to their death for their city. The women represent the opposite of reason, emotion. They weep and swoon. They can exhibit their emotions, and will stay home to care for the children and the wounded, and mourn the dead. The battle will be won by the Horatii who will survive. The Curatii triplets will die, and peace will be restored. To contemporary French intellectuals, reason and patriotism, lacking in their King and government, had prevailed. The majority of the people’s lives had been saved.

The “Oath of the Horatii” was not only hailed as a new style for the Academy, it also was seen as a call for the men of France to behave with honor, courage, and reason against the weak and increasingly ineptitude of Louis XVI’s government. David followed in 1787 with the “Death of Socrates,” referencing Greek history. The Neo-Classical style is repeated with the main figures placed along the foreground of the painting, similar to a carved Greek or Roman frieze. The setting, costumes, and furniture are Roman. Socrates was considered a founder of Western philosophy and practiced, taught, and wrote about ethics, moral concepts of goodness, and justice. He was called a “gadfly’ by the ruling class of a declining and failing Athenian democracy. He was arrested under false pretense, tried, and found guilty of corrupting the minds of youth and not believing in the gods. Socrates was sentenced to death by drinking poison. Drinking the hemlock was seen as another example of male courage, determination, and strength. Socrates took his own life to prevent further disruption to the lives of the Athenians caused by his teachings.

When “The Lictors bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons” (1789) (127’’ x 166’’) was exhibited in the Salon in 1789, there was no doubt about the Roman subject of the painting and what is meant. Brutus was the Roman consul; and his sons had tried to overthrow him and were caught. The punishment for this treason was death, but Brutus had to issue the order. He upheld the law. It was his duty even though it meant his son’s lives. In the painting, his sons have been executed and their bodies brought home for burial. David continues in the Neo-Classical style with the Roman settings, costumes, and furniture. However, he has placed Brutus in the shadow. Having done his duty, he can now mourn his sons and show emotion, but not in public, not in the light. In this work the emotional women were spotlighted.

The intellectuals, the opposition, and David understood that this painting was specifically targeted at Louis XVI. Brutus was strength and Louis was weakness. Ironically, Louis did not get the point and purchased it for his collection. An even greater irony, David would be allied with Robespierre, the first leader of the Revolution, and was a member of the Convention that signed Louis’s death warrant. David also made the famous sketch of Marie Antoinette on the way to the guillotine. Also of note, this painting started a fashion trend. Men cut their hair short, women dressed in Roman togas and had Roman hairstyles, and Roman style furniture was seen in French houses.

Unable to solve the extreme financial distress of the French Government caused his predecessor Louis XV, Louis XVI called the national assembly, the Estates General, to meet at Versailles. It had not been called since 1614. The three estates were the nobles, clergy, and commoners. David was commissioned by the Society of Friends of the Constitution representing the Third Estate (commoners) to paint this event. On June 20, 1789, although they represented 98% of the population, the Third Estate was locked out of the larger meeting. They moved to the royal indoor tennis court and took the famous oath never to separate until establishing a new written constitution. Louis XVI agreed to the constitution, but he soon reneged on the agreement. On July 14, 1789, the Bastille was stormed and the French revolution began.

David’s drawing was eventually to be made into a painting, but the funds were not available. Prints were made and sold, but the painting was not made. Under the first revolutionary government of the Jacobins, headed by Robespierre, David was elected to the National Convention in 1792. He became minister of arts. He dismantled the Academy, opened the Louvre as a museum, and designed uniforms for the elaborate Jacobin ceremonies. To the members of the National Convention Robespierre was the leader, but David was nicknamed the “Robespierre of the brush.”

Jacobin leader Marat was assassinated in 1793, and Robespierre was arrested and beheaded in 1794. David was imprisoned in the Luxembourg Palace, but he was allowed to paint. Granted amnesty in 1795, he continued to paint and to teach. The revolutionary governments continued to change hands and blood continued to flow. David painted the “Intervention of the Sabines” (1799) (12’ 8’’ x 17’2’’) to celebrate his wife’s loyalty to him and to influence the current government. At the founding of Rome, Romulus and his men needed women to populate and grow the city. They raided and abducted women from the surrounding areas. Several years later the Sabine men attacked Rome in revenge. David depicts the Sabine woman, showing their courage and determination in placing themselves and their children between to two armies to stop the slaughter. After marriages and births, the two armies were now related as fathers-in-law and sons- in-law, and the bloodshed needed to end. The women succeeded and the battle ceased. The two sides became one.

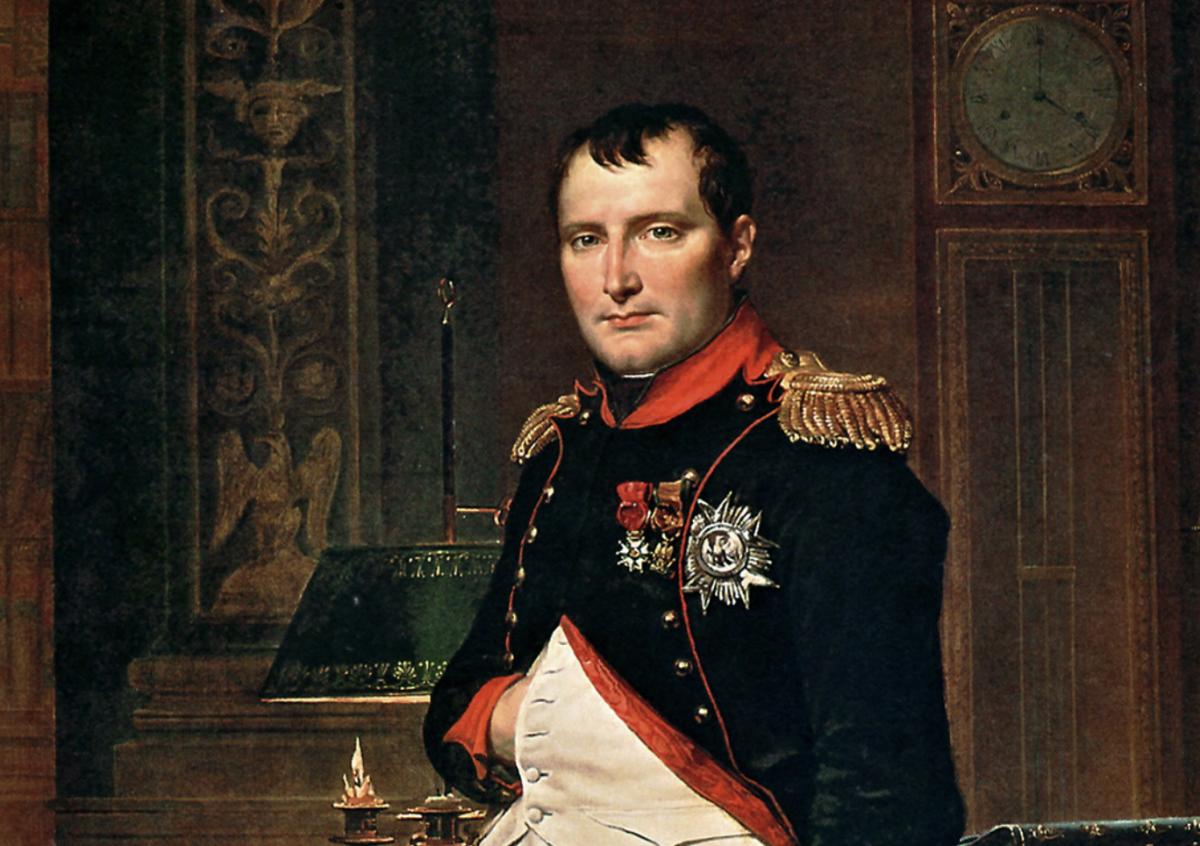

One last political intervention in David’s life and art was the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte from 1799 until 1814. General Napoleon followed Roman military history and saw David’s paintings as representing the Roman style government he wished to impose. Napoleon became King and France and David became First Painter to the King. He and his students chronicled the rise of Napoleon and his exploits as conqueror. David and his students became propagandists for Napoleon. In “Napoleon Crossing the Alps” (1801-05), which he did on the back of a donkey, the flamboyant General is astride a rearing stallion. It was one of five David painted. In 1808, David painted the enormous “The Coronation of the Emperor Napoleon I and the Crowing of the Empress Josephine in Notre Dame Cathedral on December 2, 1804 “(1808) (20.8’ x 32.1’), more simply known as “Le Sacre.” It depicts Napoleon’s self-elevation from King of France to Emperor, the title indicating his intention to conquer and rule all of Europe. In the ceremony, a standing Napoleon took the crown from the hands of the Pope and placed it on his own head. He would not bow to anyone, and no one but himself could grant him the crown. In the painting Napoleon commissioned from David, Napoleon already wears the Emperors crown, and he is crowning his wife Empress. Napoleon said he would not be depicted on his knees to anyone. Napoleon also insisted all the attendees be depicted and all of those were to be portraits. They were. On view in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, is David’s “Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries” (1812).

When Napoleon fell in 1814, so did David. He was exiled to Brussels where he continued to paint until his death in 1825. Although the governments changed and French art styles would go through many changes, David was held in high esteem by the Academy and artists. In 1860 the famous French painter Delacroix called David “the father of the whole modern school.”

“History repeats itself, but in such cunning disguise that we never detect the resemblance until the damage is done.” Sydney J. Harris [20th century American journalist, Chicago Daily News and Chicago Sun Times]

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Liz Fisher says

Fascinating article—now I will have to research David and this period in French history. Thanks, I am enjoying the series, and look forward to the next Looking at the Masters write up.