Resurrection images showing Christ rising from the tomb were not part of early Christian art since the Gospels do not describe the event. The Resurrection was first represented by the two Greek letters Chi Rho (XP), spelling Christos. The letters intersect each other. The “Resurrection” (c. 350 CE) is a panel from a Roman sarcophagus. The wreath that encircles the letters was a symbol of victory first used by the Greek god Apollo. The Chi Rho and wreath image can be traced to the Roman Emperor Constantine I (280-337 CE), who dreamed that he would win the battle the next day if his soldiers fought with Christian crosses drawn on their shields. He was victorious at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312 CE), and he gained sole control of the Roman Empire. Attributing his victory to the Christian cross, he declared the empire was Christian. Constantine was to be called the Holy Roman Emperor, and he adopted this symbol as his standard. To early Christians the wreath symbolized the victory of Christ over death through the Resurrection. It also symbolized the ascendance Christianity.

In this rare image, the stem of the Rho is extended to create a cross. Sitting on the arms of the cross are two doves, symbols of the Holy Spirit and peace. Two pieces of cloth wrapped around the bottom of the wreath flutter toward the doves. Beneath the cross are two Roman soldiers. The figure at the right, leaning on his shield, appears to be asleep. At the left, another Roman soldier, hands folded in front of him, looks up at the cross. Corinthian capitals top the columns on either side of the image, and the outspread wings of an eagle, a symbol of Rome, form an arch across the top. The eagle holds the top of the wreath in its beak. The two heads that appear to either side of the eagle’s wings could be angels. However, the rareness of this image at the time makes such an interpretation questionable.

Images of the Resurrection appeared in the Eastern Church before they did in the Roman Catholic Church. It was not until the 12th Century that depictions of Christ emerging from the tomb developed. The “Resurrection” (14th Century, Nottingham, England) (Walters Museum, Baltimore, MD) is carved from alabaster, a stone plentiful in the area of Nottingham. The image was fully developed by that time, and Christ, having thrown off the cover, steps out of the coffin. Anatomy was being explored but was far from conquered, and Christ’s proportions and movement are awkward. The artist has shown that Christ’s ordeal on the cross left his body emaciated, most obvious His shrunken chest.

Three of the four Roman soldiers left to guard the tomb are asleep, while a fourth awakens to witness the miracle. Christ steps from the coffin, His foot on the sleeping soldier beneath it. Perhaps as the result of the artist’s lack of skill; the risen Christ’s body seems to be weightless. The alabaster from which “Resurrection” is carved has a soft texture; therefore, it was easy to carve. The translucent, pearl-like glow of the surface of alabaster made it a popular choice for religious carvings all over Europe.

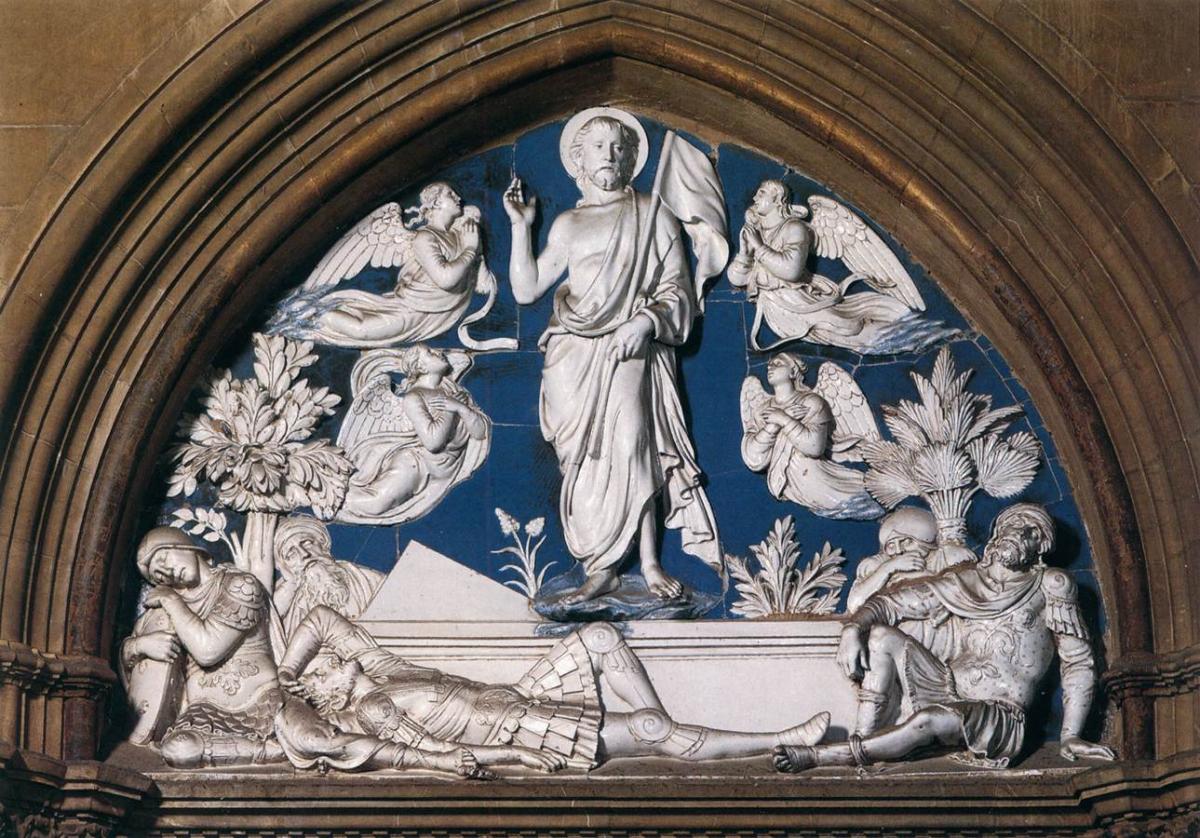

Luca della Robbia (1435-1525) was a Florentine artist famous for his glazed terracotta (cooked earth) sculptures. He developed a colorful reflective glaze fired over terracotta. It was suitable for both indoor and outdoor spaces and for small or large pieces. A well-respected stone sculptor, Luca’s first commission in which he used this new technique were two lunettes “Resurrection” and “Ascension” ordered by the Vestry Board of the Cathedral of Florence. “Resurrection” (1442-1445) was placed over the north door of the New Sacristy.

The image of the risen Christ hovering on a cloud was first adopted by artists in Italy in the 12th Century. The lid of the sarcophagus lies to Christ’s right. His right hand raised in blessing. In His left hand He holds a banner, symbolic of victory over death. Five Roman soldiers assigned to keep watch over the tomb are asleep. Trees and flowers on either side of the sarcophagus and Christ are in bloom. Four angels, in praying poses, rejoice as they accompany Christ’s resurrection. Della Robbia employs only the white and cobalt blue glazes in this work. Later works have an expanded palette of yellow, green, and purple. The della Robbia family of artists kept the technique a well-guarded secret.

The Council of Trent (1545-1563) decreed the hovering/floating figure of Christ inappropriate and demanded artists return to the image of the risen Christ standing on the ground. Many Italian artists ignored the Council. “Resurrection” (1593) (85.4’’ x 62.9’’), by Italian Baroque artist Annibale Carracci, continued the tradition of the hovering Christ figure. Carracci, in true Baroque fashion, created a highly emotional scene. Christ swirls upward out of the sarcophagus into the golden glow of Heaven. The sense of the miraculous is increased with the sarcophagus’s top remaining in place, the seal unbroken, and the Roman soldier asleep undisturbed on top.

The sarcophagus is placed on the diagonal, as are most of the people and objects in the composition. Diagonals replace horizontals and verticals of the Renaissance to create a sense of movement, tension, and emotion so important to the Church in the Baroque era. The Protestant Reformation had drawn many people away from the Catholic Church. The Council of Trent concluded that one way to win them back was to present art that made them feel like witnesses to liturgical events. Carracci employed the Baroque technique of chiaroscuro, strong darks and lights, that provides drama. Several witnesses are asleep, but Carracci has added several civilians who react emotionally to the angels and the risen Christ.

The scene is set as the sun begins to rise in the dark blue sky. Angels and cherubs are lit by the golden glow of Christ. Visible on the palm of Christ’s upraised hand and on his foot are the wounds from the crucifixion, and on His chest the gash delivered by the Roman soldier, Longinus, to make sure He was dead. In His left hand is the unfurling banner of victory topped by a cross. In the heavens, swirling draperies and dark clouds are employed to separate Earth from Heaven. Three uses of red, on figures to the left and right of the sarcophagus and on an angel above, create a triangle to lead the eye upward. Touches of blue also lead the eye through the painting from front to back. Annibale Carracci painted “Resurrection” for his family’s private chapel in Palazzo Luchini, Bologna.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring with her husband Kurt to Chestertown six years ago, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and Chesapeake College’s Institute for Adult Learning. She is also an artist whose work is sometimes in exhibitions at Chestertown RiverArts and she paints sets for the Garfield Center for the Arts.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.