“We may also suspect that they (majority opinion) suspected that emergency powers would tend to kindle emergencies.” Supreme Court Justice Jackson (Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer 1952) decided President Truman did NOT have the power to take over US steel companies.

Few Americans outside a gaggle of scholars, Constitutional law savants and national security buffs could possibly be familiar with the easy availability US presidents have to broad “dictatorial” powers. They have been drawn on by chief executives throughout US history, usually sparingly, but sometimes not. Last year’s January 6, 2021 insurrection and assault on the US Capitol generated, for different reasons, considerable attention to them.

Wanting to learn the reality and extent of these powers, I did some research. What I found was startling. The President can do virtually anything, if s/he words it right. In past years, Presidential applications of these authorities have at times, seriously, even severely affected the lives of numerous Americans. And appeared to others then, to contradict citizens’ traditional beliefs in their Constitutional and statutory rights and privileges.

In general, Americans and our political leaders have successfully relied on the probity and moral judgment of our Chief Executives to avoid misusing these literally extraordinary, latent powers. There have been a few exceptions.

However, we’re now in a somewhat distorted political environment featuring personal vitriol and at times, brutality. it seems prudent to understand the nature of these very potent presidential action-options when an increasing number of Americans believe violence is acceptable to correct even false assertions of political wrongdoing. These conditions, unless countered, could worsen and lead a president to draw on these powers.

Martial Law

What does it actually mean? Simply put, it refers to those times when an American region, state or municipality or the entire country (only once, during Civil War), is placed under the control of military forces. Both the President and Congress have the authority to impose martial law, because both can assert control over national guard units. And in the case of the President, over Federal Forces as commander-in- chief. There are some constraints (Posse Comitatus Act -1878), but Congress has given considerable latitude to the White House. Governors, within their state borders, can also declare martial law.

In the United States, martial law has been imposed infrequently over 2 plus Centuries (68 times) usually in times of war, public unrest/conflict/violence or in cases of natural disasters. Some examples: New Orleans during War of 1812, the Great Chicago Fire (1871), the San Francisco Earthquake (1906), the Omaha Race Riot (1919) and the West Coast Waterfront Strike (1934) and after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (1941).

And more recently, to enforce Federal school integration laws in Little Rock ,Arkansas (1957) and to counter violence in the Cambridge, MD. racial riots (1963).

Habeas Corpus and the 5th Amendment

Conceptually, the declaration of martial law is tied to the suspension of the Constitutional right of Habeas Corpus (Art. 1, Sec. 9) , guaranteeing US citizens, a hearing and trial upon lawful arrest. Section 9 states this right “…will not be suspended unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it.”

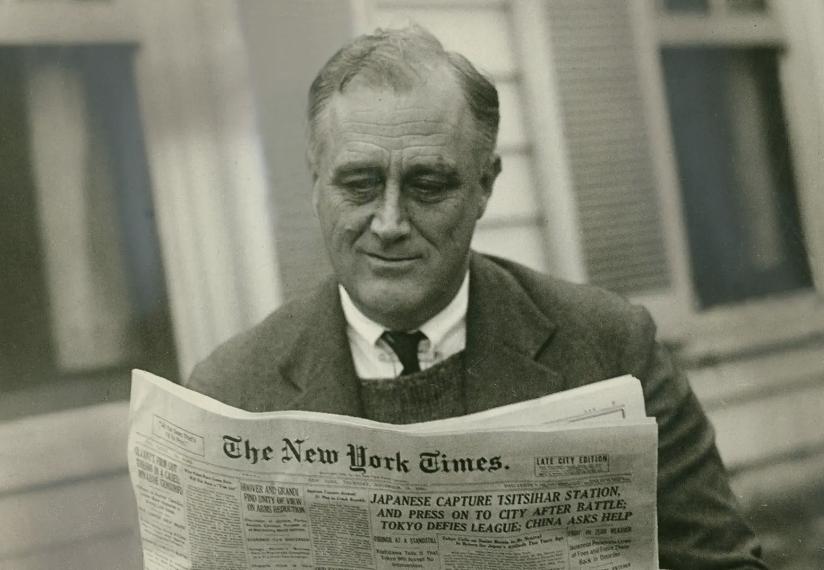

The most egregious example of misuse, occurred in 1942 when President Roosevelt issued executive order #9066 suspending 120,000 Japanese-Americans protection under Habeas Corpus and the 5th Amendment. The latter holds that: “No person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process.” The last Japanese Americans were released from US internment camps in March, 1946.

Some commentators also include President G.W. Bush’s introduction of a torture program after the 9/11 attacks, in this category of excessive use of these powers..

Emergency Presidential Authorities

During the late 18th, 19th and the early 20th Centuries, Congress passed laws giving the president (Executive Branch) considerable flexibility of action when confronting military, economic and labor crises. Prime among them, is the 1807 Insurrection Act that allows the president to deploy Federal troops either upon the request of a state governor or legislature, to stop an insurrection within their borders. Or if s/he believes it is impractical to use normal courses of action, Federal forces may be used to suppress: “insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination or conspiracy that impedes the course of justice.” Last Century, these legislated powers became more operationally formalized with the passage of the National Emergencies Act, requiring the president to declare a state of National Emergency before drawing on them. Once invoked, chief executives over many years seldom terminated them. One example, President Truman’s use of the National Emergencies Act (1950) – Korean War -was still in force, and was used during the Vietnam War.

These Emergency Powers address more than the military and can include agricultural exports and the validity of public contracts. Curiously, there is no requirement that the powers used, be related to the rationale behind the Declaration of a National Emergency. And there are other laws that allow the Executive Branch to take extraordinary action under certain conditions, without a declaration of emergency. It’s complicated.

Cyberspace, the Communications Act of 1924 and Twitter

In 1942, Congress amended the Communications Act to give the president the authority to close or take control of “any facility or station for wire communications”, upon his proclamation “that there exists a state or threat of war involving the United States.” Finding a “threat of war” in 2022, is not a problem.

If Elon Musk proceeds to liberate Twitter from any constraints and President Biden or his successors decide as President Trump did, that the “…search engines were RIGGED to serve up negative articles about him”, maybe Musk or other big internet companies should become concerned about a possible application of Emergency Powers, including a 21st Century reinterpretation of the Communications Act.

On November 8, 2022 the Midterm Elections will take place across the United States and determine the composition of the Congress, the occupants of various governors’ mansions, state legislatures and multiple local offices.

For weeks, media commentators and multiple social media platforms have been reminding Americans of the increasing levels of politically related violence and last year’s January 6 insurrection. Many candidates have been asked:i “will you accept the results of the election, if you lose?” The absence of a loud YES from many has led to speculation that accusations of Voter Fraud will surface again as they did in 2020, and lead to similar instances of mob violence.

And then on October 28th, the husband of Speaker of the House,Nancy Pelosi, was viciously attacked in their San Francisco home by a hammer-wielding man yelling “Where’s Nancy?”

None of the foregoing has anything to do with the presidency or the incumbent’s special powers. True, but the current political atmosphere is infected with hatred, anger and a growing fear or anticipation that more violence will erupt following November 8th. Absent, some “deus ex machina”, it is unlikely all popular political attitudes will substantially moderate before the 2024 Presidential Election.

And who knows how a new president will view these dormant extraordinary powers after January 20, 2025?

Tom Timberman is an Army vet, lawyer, former senior Foreign Service officer, adjunct professor at GWU, and economic development team leader or foreign government advisor in war zones. He is the author of four books, lectures locally and at US and European universities. He and his wife are 24 year residents of Kent County.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.