Baltimore City leaders knew they were coming.

And yet, the newest population numbers from the U.S. Census, delivered Thursday on the hottest day of the year, hit them like a torrent of cold water in the face.

Baltimore’s dramatic 5.7% population loss over the past 10 years means the city is sure to face a corresponding loss of political clout in the decade ahead — no matter how many allies it has in the highest echelons of power in Annapolis.

That’s one of many political threads that will be pulled over the next several months, as state politicians and policymakers seek to use the Census data as part of the recipe for congressional and legislative district maps that will be in place until the elections of 2032.

Baltimore wasn’t the only Maryland jurisdiction to see significant population losses — far from it. But the latest numbers did produce a significant degree of handwringing in the city.

Donald C. Fry, president and CEO of the business group the Greater Baltimore Committee, called it “unacceptable for a city with the many positive attributes Baltimore has, from its affordability, diversity, strong neighborhoods, historical and cultural attractions to world class healthcare and universities, to lose residents.”

Baltimore Mayor Brandon M. Scott (D) scrambled to put the dreary numbers in historical context and asserted that city leaders are putting policies in place to stanch the bleeding and slowly build back the city’s population.

“Today’s population figures are the culmination of more than 70 years of population decline, showing why we must pivot from the status quo towards inclusive economic policies that improve the lives of our legacy residents, while attracting new residents,” Scott said Thursday. “Understanding that much of Baltimore’s 21st century population loss has been driven by an exodus of African American households, my administration will be focused on equitable economic development. We can no longer leave any corner of our city behind.”

Census figures help determine how much federal aid is distributed to states and local jurisdictions, but they are also key weapons in the raw redistricting political battles that will follow.

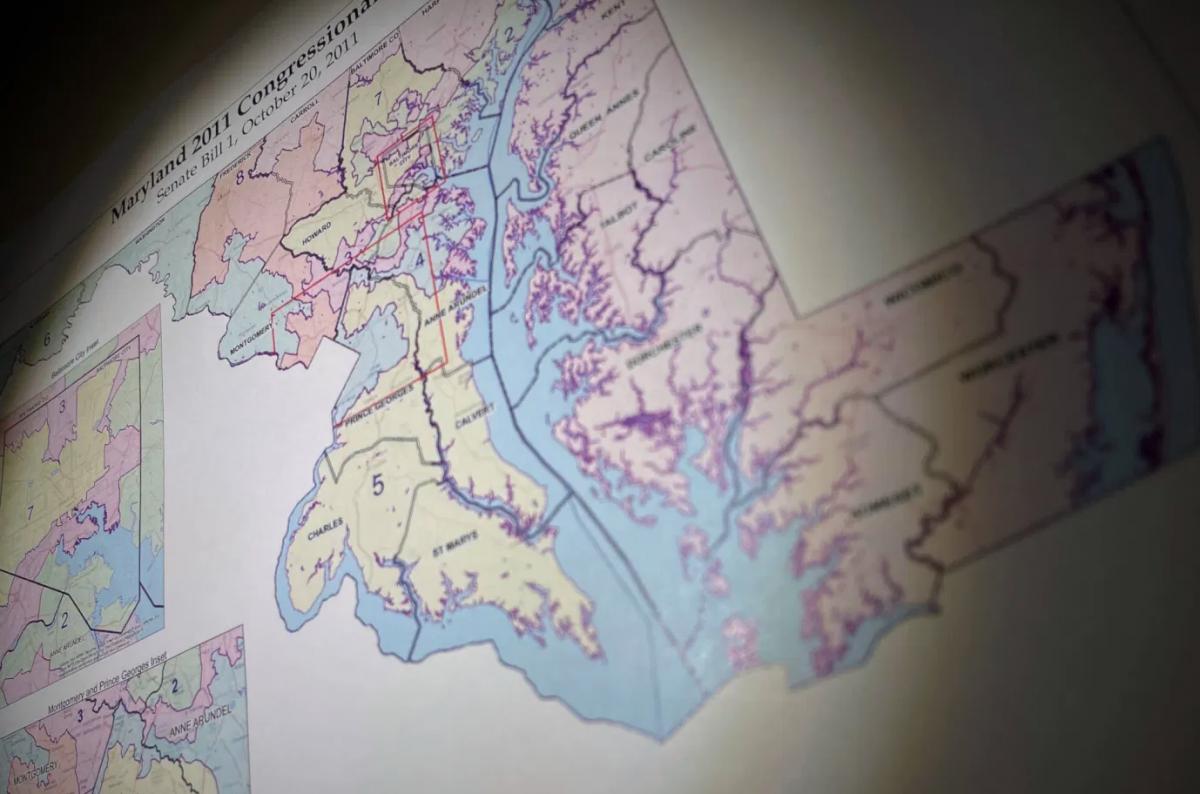

Overlaying Maryland’s current congressional and legislative district maps with the map of of the latest county-by-county population trends is an interesting exercise.

Even the most gerrymandered political maps must start at the corners of the state — far Western Maryland and the Lower Eastern Shore. And at both poles of the state, the population, with the exception of Wicomico County on the Shore, has declined over the past decade. That’s part of a national trend that saw rural population drop sharply while it increased in urban and suburban areas — and will have implications for what congressional and legislative boundaries in Maryland look like.

From the minute he took office, Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr. (R) has sought to inject himself in the redistricting process — or at least take the power away from the Democratic supermajorities in the General Assembly and, by extension, the most senior Democrats in the state’s congressional delegation. But the fact remains that legislative leaders, working in tandem with U.S. House Majority Leader Steny H. Hoyer (D-Md.), will have the most say.

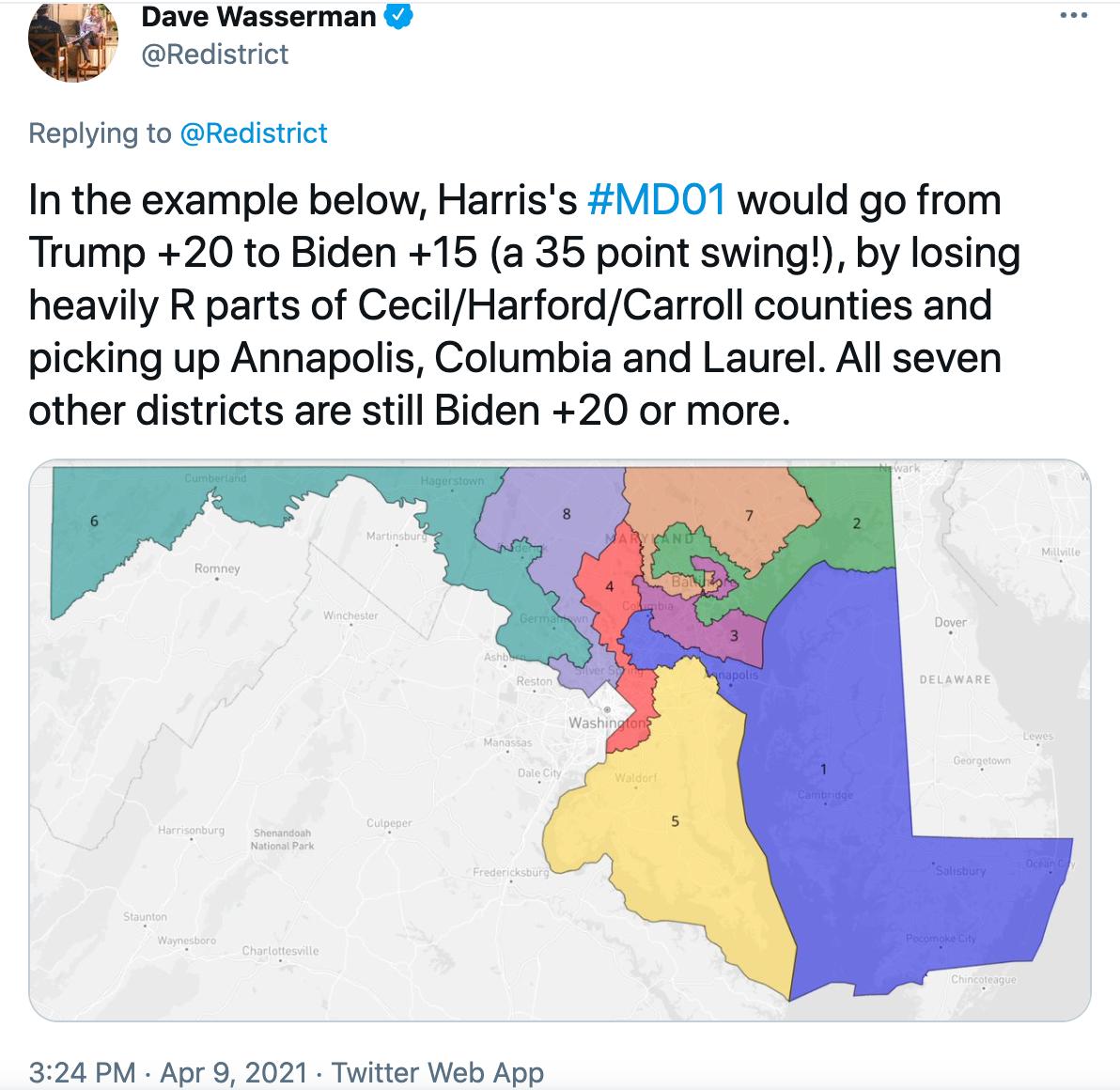

For State House Democrats, knowing that Republican legislatures will attempt to help the GOP seize control of the U.S. House of Representatives by muscling through baldly gerrymandered maps, there will be temptations to create an 8-0 Democratic congressional map in Maryland (the state delegation currently has seven Democrats and one Republican). But the Census figures show that population trends in certain red states weren’t as stark as they could have been — meaning Republicans won’t have quite as much power to bludgeon Democrats in those places as they might have expected.

“Early read: based on the strong urban and weaker rural numbers I’m seeing, this is a much more favorable Census count than minority advocacy groups/Dems had feared,” Dave Wasserman, the House analyst for the nonpartisan Cook Political Report tweeted Thursday.

As a result, Maryland Democratic strategists believe, party leaders are more likely to try to produce a 7-1 Democratic congressional map again — albeit one that is cleaner, with fewer tortured contours, and that is less susceptible to lawsuit than the post-2010 Census map.

Baltimore City currently has three congressional districts cutting through its borders. Anne Arundel County has four. Howard County has three. Baltimore County has four. The result is messy, nonsensical districts in the central part of the state. That may change.

With population losses on the Eastern Shore, the 1st Congressional District, held by the state’s lone Republican member of Congress, Rep. Andrew P. Harris, will probably need to gain more territory on the western side of the Chesapeake Bay. Where those precincts are added may determine how competitive a re-election race Harris will face in 2022 — most likely against former state Del. Heather R. Mizeur (D).

Maryland mapmakers actually have more flexibility when it comes to drawing legislative districts — where population variations of as much as 10% are permissible (each congressional district must contain the exact same population, to the extent possible). Even so, Baltimore City, which has steadily lost representation over the past few decades, is likely to lose more seats.

It’s already accepted wisdom in Annapolis that the 44th District, which currently contains a one-member House subdistrict in Baltimore City and two House seats in Baltimore County, will push out into the county exclusively — meaning the legislative tenure of Roxane Prettyman (D), who has been recommended by the Baltimore City Democratic Central Committee to fill a vacancy in District 44A, could be short-lived.

Another Baltimore City legislative district that has seen modest population growth, District 46, may have to lose some city precincts to make whole other city districts — and could extend south toward Glen Burnie or even BWI Thurgood Marshall Airport.

Howard County’s population growth means it may no longer have to share one legislative district with Baltimore County. Frederick County’s population growth means it may not have to share a legislative district with Carroll County. Southern Maryland’s representation in Annapolis is also likely to grow — though Democrats undoubtedly will try to maximize their advantage in fast-growing Charles County, which, according to the latest Census figures, is now over 50% Black.

And population losses in Garrett and Allegany counties mean the 1st legislative district will necessarily have to push farther east into Washington County.

The Maryland Department of Planning will now take the Census figures and spend the next few weeks adjusting them to account for the state’s incarcerated population. Under state law, incarcerated individuals are countered as residents of the jurisdictions where they previously lived, rather than the jurisdiction of the prisons where they are serving their sentences. This could help limit Baltimore City’s population loss to a small degree.

Hogan and legislative leaders are relying on the work of dueling redistricting commissions to help guide them on the maps they will propose in an upcoming special session of the General Assembly to finalize a congressional map, and during the regular 2022 session when legislative lines must be adopted. Even though Democrats have the upper hand, Hogan was already attempting to grab the moral high ground on Thursday.

“All across our state, Marylanders are demanding an end to partisan gerrymandering from partisan politicians in the legislature and supporting the work of the independent and nonpartisan Maryland Citizens Redistricting Commission,” he said on Twitter.

By Josh Kurtz