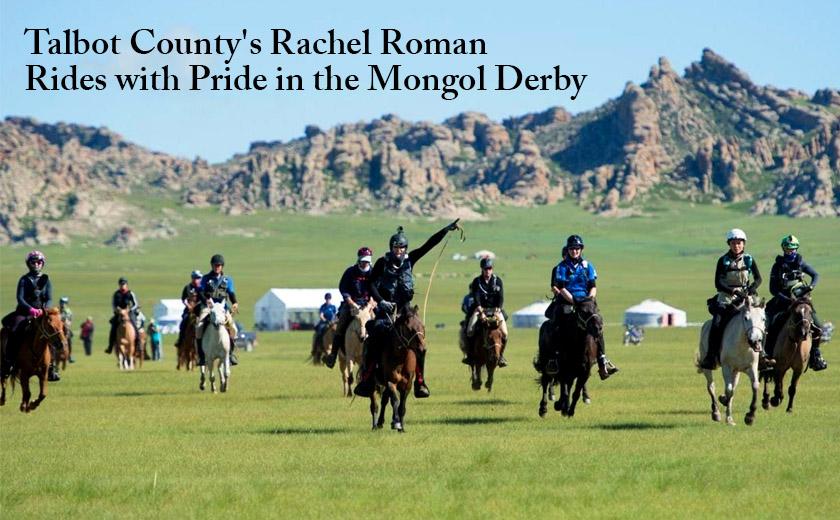

It’s a little after dawn somewhere in a remote part of the Mongolian Steppe. The rider has just been helped onto a native and semi-wild Mongolian horse. The temperature is brisk—in the mid-30s and does not foretell the almost 80 it will be later in the afternoon. If all goes well, the rider will travel 75-100 miles today on a path which loosely follows the horse messenger system developed by Genghis Khan in 1224. But this is not a guided re-creation. The course is not marked, and the rider must rely on their skills and a GPS tracking system that will get them through the over 600 miles (1000km) adventure. They will stop every 25 miles at horse stations (uutuus) to swap horses.

By 8PM, they will have traveled 12-14 hours, and a nomadic host family will give them dinner and a place to rest for the night. With a lot of physical and mental stamina, this will be the routine for the next 7-10 days. With a lot more luck, they may be in the 35-40% who finish the race. This is the Mongolian Derby, also known as the longest and toughest horse race in the world.

To understand why someone would want to take part in this journey, talk to 27-year-old Rachel Roman. Roman, an Eastern Shore native applied on a whim after hearing about the race online from former participants. Her reasons were no different from others, who like her, list horses, adventure, and outdoors as life passions. Even though she was not experienced in endurance riding, there was something about her application that stood out to the interviewers. Whatever it was, she is one of only 40 riders worldwide who was accepted to compete this August.

Since then Roman has been relentlessly training and spreading the word about the race. “I am also using the race,” she says, “as an opportunity to raise funds and awareness for the work the Nature Conservancy is doing in Mongolia in their efforts to preserve one of the last wild places on earth and the nomadic communities that depend on that environment.”

Raising funds is vital to her taking part in the race, as well. Her GoFundMe site will help offset the steep $15,000 entry fee and travel expenses and includes the $7,000 she wants to raise for the Conservancy. It helps that Roman is familiar with outreach and fundraising, being involved in the nonprofit environmental field. She previously worked for The Eastern Shore Land Conservancy and is currently employed by The Nature Conservancy in Washington (State). She chose Seattle, she said, because it most closely reminded her of home “I wanted to be near water and great outdoor spaces. The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary by size, and Puget Sound is the largest estuary by volume. I consider it the West Coast Chesapeake Bay!”

When not at her 9-5 job, Roman spends every available moment preparing for the race. Part of the challenge has been to spend as much time in the saddle and on as many horses as possible. She leases a horse and rides it daily. She has a trainer that is helping her with strength and endurance. She has a spin bike and gets on it every day. She walks to and from work. On weekends she rides 7-10 horses at a dressage farm. But dressage, with its synchronized and prescribed movements, differs from what she will encounter and ride during the competition.

When not at her 9-5 job, Roman spends every available moment preparing for the race. Part of the challenge has been to spend as much time in the saddle and on as many horses as possible. She leases a horse and rides it daily. She has a trainer that is helping her with strength and endurance. She has a spin bike and gets on it every day. She walks to and from work. On weekends she rides 7-10 horses at a dressage farm. But dressage, with its synchronized and prescribed movements, differs from what she will encounter and ride during the competition.

The native horses used in the derby have changed little since the time of Genghis Khan. They are short and of stocky build, usually between 4-5 feet tall, with short, strong legs. They are also incredibly tough and well-adapted to the extreme temperatures, lack of food and water, typical of the Steppe environment.

Around 1,400 horses from local herders are chosen and trained for the Derby. Riders are given a start and an end point and 10 days in which to complete the adventure. Winners usually finish within seven days, but most do not. There are very few rules and most have to do with the horse’s welfare. It is the Derby’s primary concern and built into every aspect of the race. Because of the horse’s stature, riders can weigh a maximum of 188 lbs. and carry no more than 11 lbs.in their pack. This is also the reason why last year 70% of the competitors were women. Participants, who last year ranged from 19 to 70 years of age, will ride between 24-26 different horses since each horse is used for only one leg of the competition. Riders switch horses every 25 miles, and an international team of vets makes sure that all horses are ‘roadworthy’ when they leave the urtuus and not in distress when they are brought in. If a horse is dehydrated or stressed, a time penalty is issued (usually two hours). If a rider consistently brings in an overworked horse, they will be kicked out of the race.

Choosing your horse is part of the strategy and done on a first come, first served basis. “My goal,” says Roman, ‘is to look for a horse that is not completely wild. Some will be actual Mongolian race horses which, I heard, are unbelievable to ride. I’m hoping to get one where you basically sit there and hang on. I’m going to look for horses that show a little bit of age; look like they’ve done the race before. The worse thing, I’m told, is to have a horse that won’t go forward or bucks you off. The problem is you don’t know which ones have been handled more or who are used to the saddle. The only thing Mongolians can do is put the saddle on for you, help you get on, and then they let go. The rest is up to you.”

All riders must dismount by nighttime and may choose to stay with a local family. In fact, part of the entry fee is compensation to the approximate 250 Mongolian families who participate in the race and supply horses, shelter, and meals for the riders. Food raises concern for Roman. “We eat whatever the local families make us,” she says. “Items such as fermented mare’s milk, tripe, goat, sheep, and warm vodka is part of the diet. It’s heavy on meat and different from the meat we eat here. I’m not quite sure how to prepare for that aspect. I eat pretty healthily; lots of vegetables, it’s going to be difficult for me. It’s one piece of my training I have yet to figure out—how to prepare my gut for that.”

Roman admits that a large part of her training is mental preparation to be out alone and to remain calm should something go wrong. It is a concern. There has been a fair amount of race-ending injuries in prior years: falls, heat exhaustion, heat stroke, hyperthermia, intestinal issues, and even debilitating saddle sores. Should she or her horse get into trouble, there is an SOS button on the issued tracker that will activate the team of vets, ambulances, and medics on standby. “But if you hit the button you’re out of the race,” she says.

Roman is building in the time to go on some hikes before her trip to East Asia to refresh her comfort with the outdoors. A few years ago, she did a National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) course for 3 months in New Mexico. Says Roman, “I learned a lot about the wilderness in my training. Hopefully, that will give me a little bit of an advantage over the other riders. I spent 22 days without showering in the wilderness. Some of the people might be great riders, but they haven’t had to be in the wild. We have to purify or boil our water, there won’t be any bathrooms—it will be a whole wilderness experience, and I’ve done that.”

Roman is building in the time to go on some hikes before her trip to East Asia to refresh her comfort with the outdoors. A few years ago, she did a National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) course for 3 months in New Mexico. Says Roman, “I learned a lot about the wilderness in my training. Hopefully, that will give me a little bit of an advantage over the other riders. I spent 22 days without showering in the wilderness. Some of the people might be great riders, but they haven’t had to be in the wild. We have to purify or boil our water, there won’t be any bathrooms—it will be a whole wilderness experience, and I’ve done that.”

She mentions two goals she would like to meet: Incur no time penalties and finish the race within the allotted 10 days. As for what’s next, Roman replies: “There are other adventures like this, but I don’t want to keep doing the same thing. Like with this race that I randomly applied for, whatever my next adventure will be, it will be something that just comes up, that I won’t be able to put off. I hope this race inspires others to put time aside for whatever adventure they’ve been putting off.”

The 2019 Mongolian Derby will run August 7-August 17. Each rider has their own web page with a map linked to their satellite tracker allowing friends and followers to track them live throughout the race. To find out more about Rachel Roman’s journey and follow her progress go here

Val Cavalheri is a recent transplant to the Eastern Shore, having lived in Northern Virginia for the past 20 years. She’s been a writer, editor and professional photographer for various publications, including the Washington Post.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.