Now that the General Assembly’s redistricting commission has begun meeting, even as Republican Gov. Lawrence J. Hogan Jr.’s redistricting commission continues to hold sessions, it feels a little like the varsity team has finally taken the field. With all due respect to the other redistricting commissioners.

Hogan will attempt to get as much political mileage as he can from the Maryland Citizens Redistricting Commission he assembled earlier this year, and whatever maps the commission proposes for Congress and the state legislature will undergird Hogan’s bully pulpit when he argues, yet again, that partisanship needs to be taken out of the redistricting process.

The Hogan commission itself has been a bit of a masquerade — both the notion that its work product would result in maps that actually get due consideration in the General Assembly, along with the fiction that this has really been a non-partisan effort, when one of the co-chairs, Walter Olson, a senior fellow with the right-wing Cato Institute, has been calling most of the shots. It’s the legislature’s commission that’s going to produce the congressional and legislative boundaries that get adopted — unless and until the maps get taken to court.

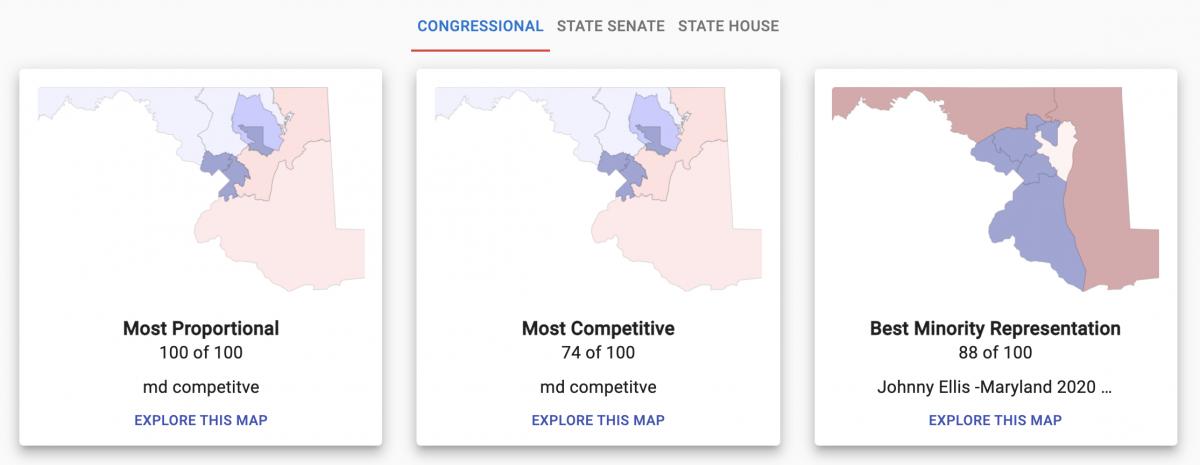

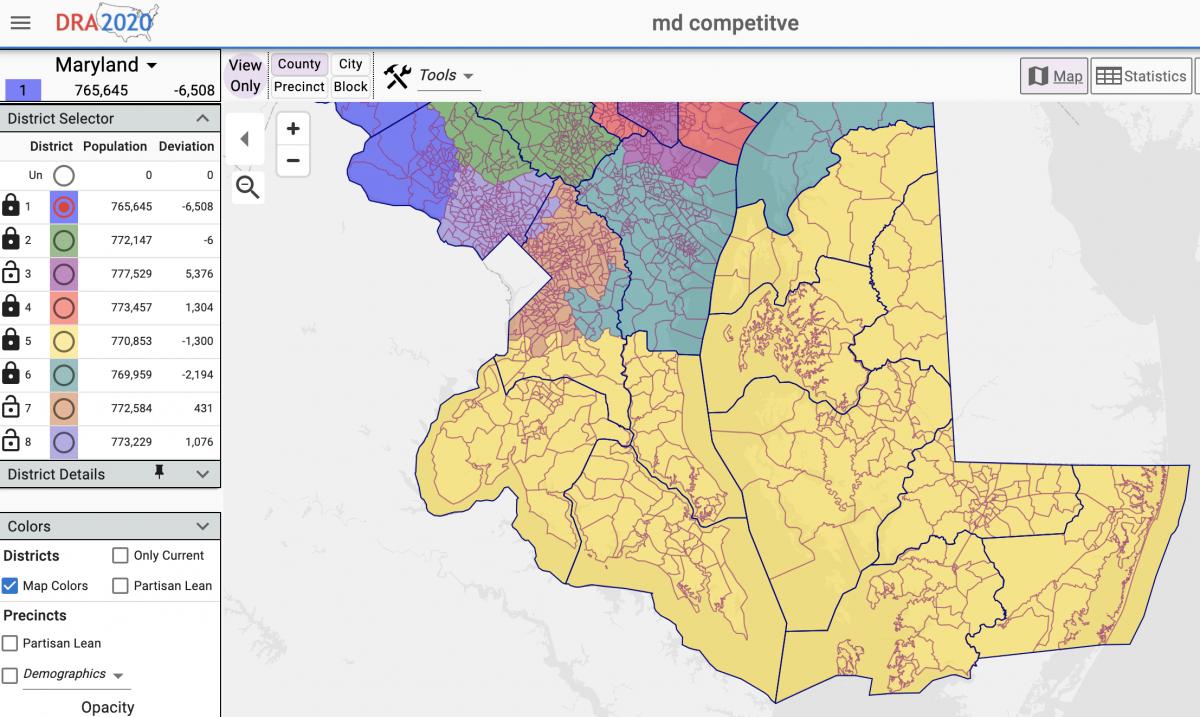

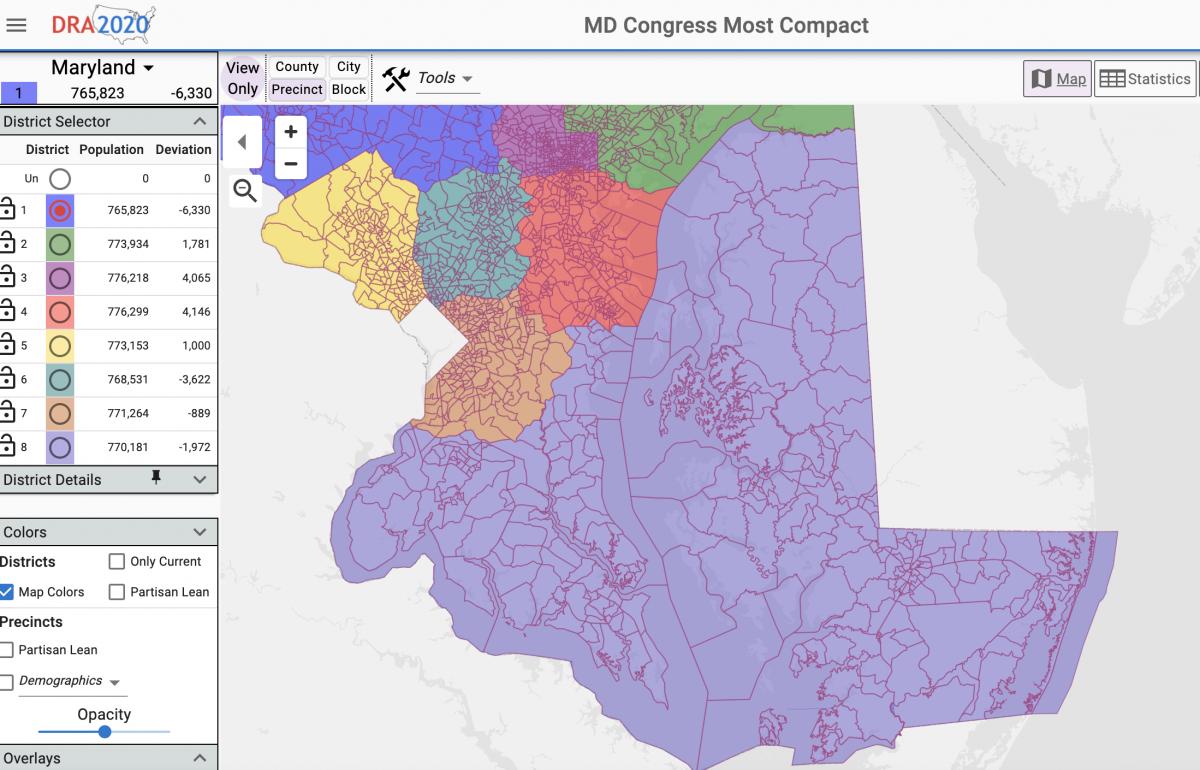

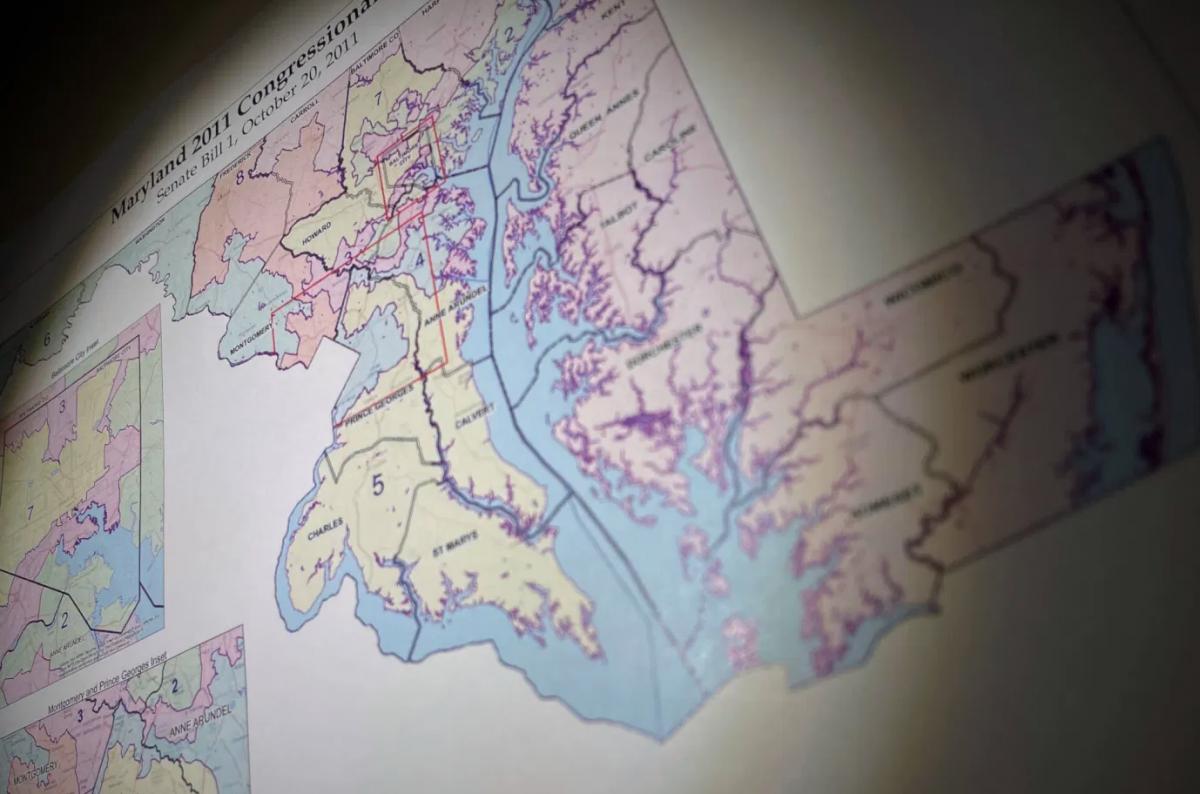

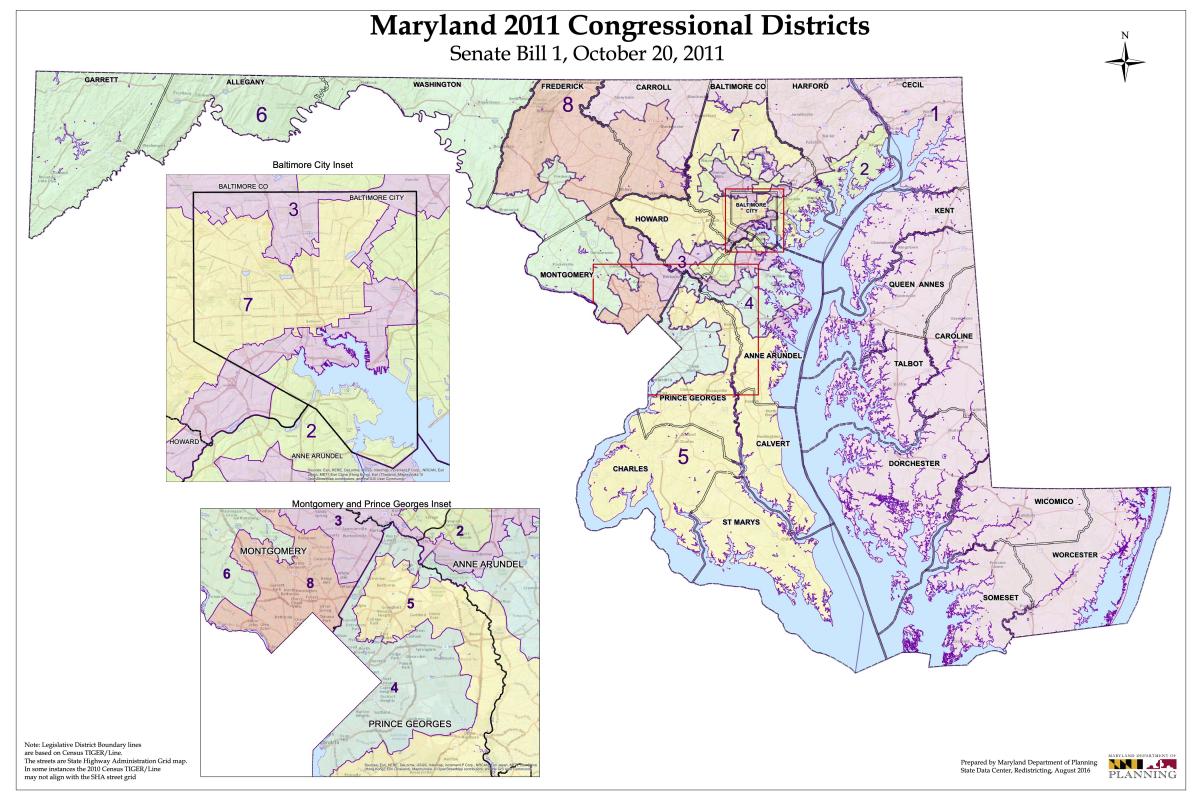

With the Democrats firmly in control of the process for now, the big question is whether they will attempt to draw an 8-0 Democratic congressional map, potentially sending Republican Rep. Andrew P. Harris into political oblivion, or whether they will keep it at 7-1 but generate a cleaner-looking product.

The draft map that the Hogan/Olson commission circulated earlier this month appeared to have five solid Democratic districts, two Republican districts, and one that theoretically could be up for grabs. That more or less accurately reflects the state’s political makeup.

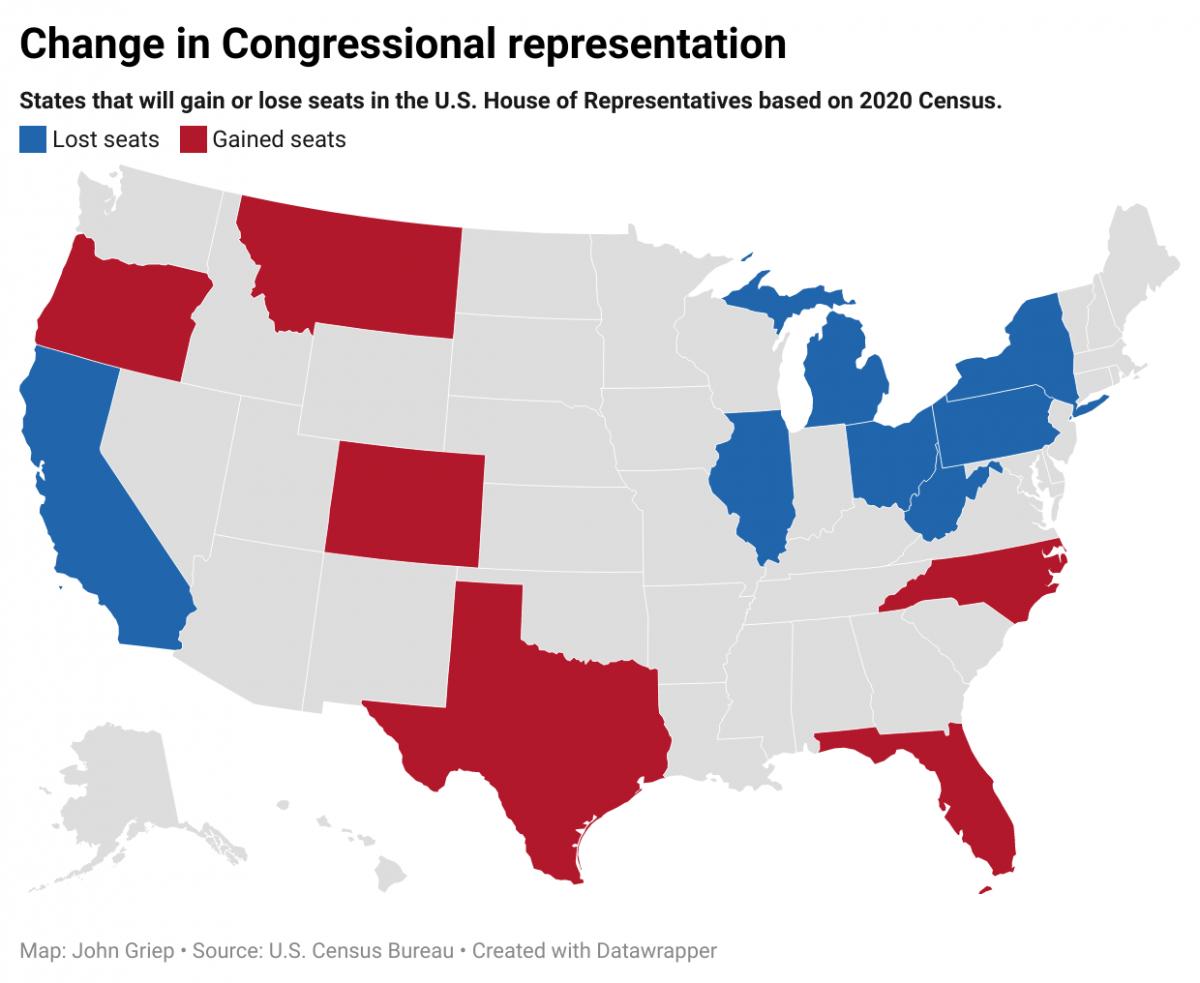

But when has that ever been a consideration during redistricting — here or in the other states where one political party controls the process? And why should Maryland Democrats “disarm” when Republicans aren’t going to do so in Texas, Florida, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania? It may be the right thing to do but it isn’t the smart thing to do in the current national political environment.

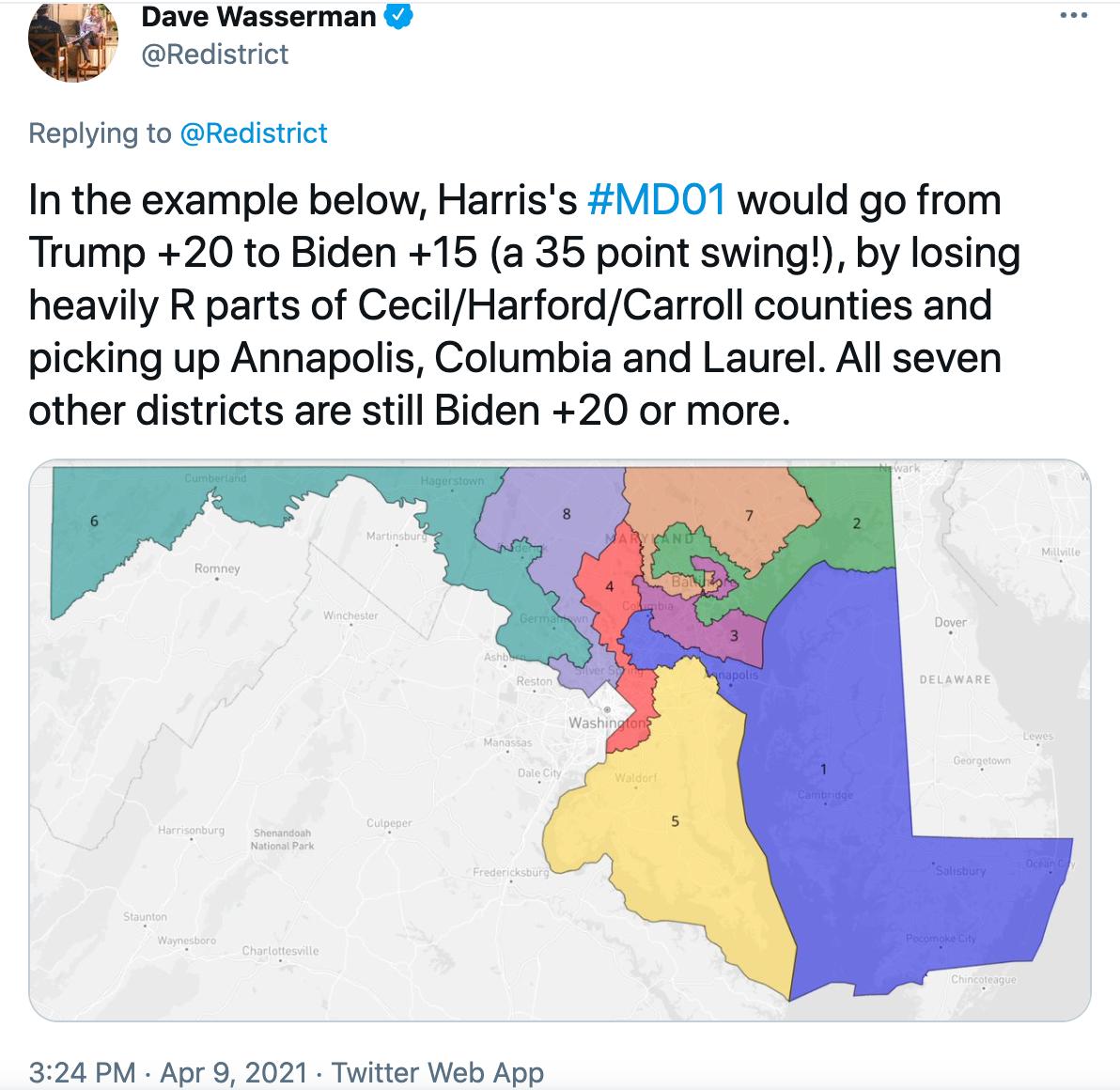

According to sources on Capitol Hill and here in the Free State, no less an eminence than U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) has been brandishing a proposed Maryland map that shows Democrats with eight seats and Republicans with zero. She is touting it to her Maryland colleagues, urging them to embrace the idea, fully aware that are very few states where Democrats can take advantage of redistricting. In fact, national political analysts say that Republicans could take over control of the U.S. House in 2023 on redistricting gains alone — never mind whatever seats they’ll invariably pick up in the midterm elections.

Drawing an 8-0 Maryland map in favor of the Democrats, believe it or not, isn’t that difficult as a cartographic and statistical exercise. The resistance comes from the Democratic members of Congress themselves, who are often reluctant to give up safe territory even if doing so would help the partisan cause.

A quick look at the 2020 election results suggests that each of the seven Democratic House incumbents from Maryland have plenty of safe territory to sacrifice: Rep. Anthony G. Brown, whose 4th District includes Prince George’s and Anne Arundel counties, won by 59 points last November; Rep. Kweisi Mfume, whose 7th District is anchored in Baltimore City but also takes in territory in Howard and Baltimore counties, won by 43 points; Rep. John P. Sarbanes, whose hideous-looking 3rd District touches five jurisdictions, won by 39 points.

Those bulging margins were followed by Rep. Steny H. Hoyer’s 38-point victory in the 5th District, which covers the three Southern Maryland counties plus Prince George’s and a piece of Anne Arundel; Rep. Jamie B. Raskin’s 36-point win in the 8th District, which is based in Montgomery but also takes in Frederick and Carroll counties; and Rep. C.A. Dutch Ruppersberger’s 35-point victory in the 2nd District, which touches Baltimore City and Baltimore and Harford counties.

Even in what’s seen as the closest thing to a competitive district in the state, the 6th — the district Democrats specifically carved out in Montgomery County and Western Maryland after the 2010 Census to pick up an extra seat — Rep. David J. Trone won by 16 points last year.

Imagine if each of these guys, minus Trone, said, “I’d be willing to shave 20 points off my victory margin.” How much easier would it then be for Democrats to put Harris’ seat in danger? Harris won reelection, by the way, by 27 points last year.

Our appointed General Assembly

When Cheryl S. Landis is sworn in as the next delegate from District 23B in Prince George’s County sometime this fall, she’ll become the 33rd member of the House of Delegates who was originally appointed to their seat. This is about one-quarter of the 141-member chamber.

And the numbers are certain to grow, with Del. Michael E. Malone (R-Anne Arundel) set to resign soon to take a judgeship, and Del. Erek L. Barron (D-Prince George’s) awaiting U.S. Senate confirmation to become Maryland’s U.S. attorney. Their slots will have to be filled as well.

The numbers aren’t any better in the Senate: In all, 12 of the 47 senators were originally appointed to their seats — five since the 2018 election alone. Add to that two senators who first entered the legislature as appointees to the House.

For those who need reminding, legislative vacancies in Maryland are filled by the governor, usually after receiving a recommendation from the relevant Democratic or Republican central committees in a departed lawmaker’s county. For Landis, it was probably pretty easy to get the recommendation: She’s the chair of the Prince George’s Democratic Central Committee. Several other appointees got their starts in politics serving on a central committee, which greased the skids for their appointment to the legislature.

Some lawmakers have tried to change the system, introducing legislation to require special elections to fill House and Senate vacancies in the first two years of the legislative term. The bill has passed the Senate in the past two years, and unanimously last year, but has stalled in the House.

It’s time to pass that bill. Is this the people’s legislature, or is it the province of political bosses and insiders?

In the meantime, we’d probably all better pay closer attention to central committee elections.

Josh Kurtz, founding editor of Maryland Matters, has been writing about state and local politics since 1995.