As a young assistant priest in a New York City church, I visited many of our parish’s elderly and shut-ins. I liked visiting. Many of my contemporary clergy didn’t. They were impatient with the inclinations of the elderly to balk at change, ruminate about health, talk about who died while fussing about changes in the churches décor or services.

I can say honestly I didn’t feel impatient. I had developed a knack for nudging the conversation in the direction of the “old days,” and how life was for these elderly in the days before my time. It was like history coming alive before me, as if I was back there. Elderly parishioners welcomed my enquiries and many of the tales I heard were spellbinding. It was a win-win.

The wheel of Karma turns. As those folks were then, so I am now. I balk at some changes and am regularly saddened by the people I’ve known who have died. I am, however, as curious about my own past as I had been about those of my parishioners in the city sixty years ago.

The experience of exploring one’s life is exciting in the way rummaging through attics can be, where over the years, all kinds of things were put away to gather dust until circumstances conspired to encourage our return to the attic. There, we rediscover what we’d long forgotten but see it with fresh eyes.

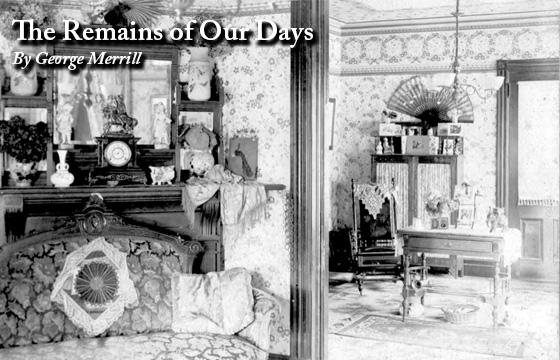

I found an old family photograph, recently. It shows the front parlor and the adjoining room in my grandparents’ home where, during my boyhood, we’d celebrate Thanksgiving. The rooms were small.

The photograph was taken long before I was born, maybe near the turn of the century. It was a grand old house located on Richmond Terrace on Staten Island, a once fashionable residential area along the Kill Van Kull, the water boundary between Staten Island and New Jersey.

I remember the house as always filled with smoke – from my grandfather’s and my uncles’ pipes and cigars – along with the lingering smell of Yardley lavender perfume that my grandmothers and great aunts wore with their holiday finery. The collective aroma became for me a kind of tribal scent by which I knew I was home among my own native kin.

In the room, bric-a-brac, knickknacks, gewgaws, photographs, odds and ends of every description covered the surfaces of mantels, tables, a china cabinet, and even the floor. There, two cuspidors sat prominently on either side of a table in the middle of one room.

The fireplace was black wrought iron. On its mantelpiece, among various vases and statuettes, sat a clock with two horses on top bearing the triumphal figures of what I guessed were conquistadores. The table in the middle of the room was also filled with photographs and I saw the black ivory elephant that had been there when I was a boy. The figurine had an elegantly smooth sheen and I could never pass it by without touching it.

Walls were papered in various floral designs, crown moldings edged the upper walls and on the ceiling in the middle of the sitting room, a chandelier hung from a round plaster floret adorned with sculpted flower buds. The chandelier had three fogged glass shades in which gas flames once burned. I saw the Morris chair I eventually inherited. In this photograph, a lace doily had been draped over the back.

Seeing the picture now, I realize that in my lifetime I witnessed the remains of the Victorian era. I was enchanted with its extravagant décor, its insatiable appetite for collectibles and the intimate spaces in which people, despite limited room, maintained careful distances from each other.

The Victorian code of conduct served to manage family secrets. My widowed great aunt had the “handyman” living with her in her Victorian home next door to my grandmothers. It never occurred to me until I was in my fifties just how in those days certain personal “arrangements,” while considered abhorrent, were nevertheless quietly accommodated, and never discussed.

I adored my Great Uncle John. He was a retired New York City policeman and a bachelor. He was considered “course.” My mother liked him, too, although she occasionally complained how he liked putting his hand on her rump. That Uncle John dated Margaret – an Irish Catholic – with whom he went to bars, shocked his Methodist sisters. It was scandalous enough that Margaret was Catholic, but to add insult to injury she was also Irish. The Methodists of the family were staunchly abstemious, terminally Protestant and defiantly waspish. I never saw Margaret at family affairs, but only occasionally with Uncle John. I liked her. She was salty.

My mother resented Grandma Merrill. Years ago, when having my father’s family for Thanksgiving, Grandma Merrill spent half of Thanksgiving day instructing my mother just how the turkey should be prepared. My mother remained civil, but the invisible walls of distance were erected.

Today, at holiday gatherings, families take a minimalist view of dress codes. Come as you are is in vogue. Flip-flops and tank tops will do. Back then, I recall with fondness that when my relatives arrived for the day, everyone was dressed to the nines. Men donned suits, vests, ties, topcoats, and wore fedoras and the women came in hats, white gloves and flowered dresses. There was an implied respect in the way that even relatives, who were certainly familiar with each other, still chose to meet looking their best. Keeping up appearances is not a bad thing. It lends dignity to an occasion.

Photographs remind us of the people and places that formed our identity. They are formed partly by our sense of place and more particularly by the personalities of the people who occupied those places. In one sense we are formed like onions, less organized by a center than consisting of layers of memories that remain with us until the remains of our days.

Seeing an old yellowed photograph brings them back.

Columnist George Merrill is an Episcopal Church priest and pastoral psychotherapist. A writer and photographer, he’s authored two books on spirituality: Reflections: Psychological and Spiritual Images of the Heart and The Bay of the Mother of God: A Yankee Discovers the Chesapeake Bay. He is a native New Yorker, previously directing counseling services in Hartford, Connecticut, and in Baltimore. George’s essays, some award winning, have appeared in regional magazines and are broadcast twice monthly on Delmarva Public Radio.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.