One of the great things about writing a column is what I learn from readers.

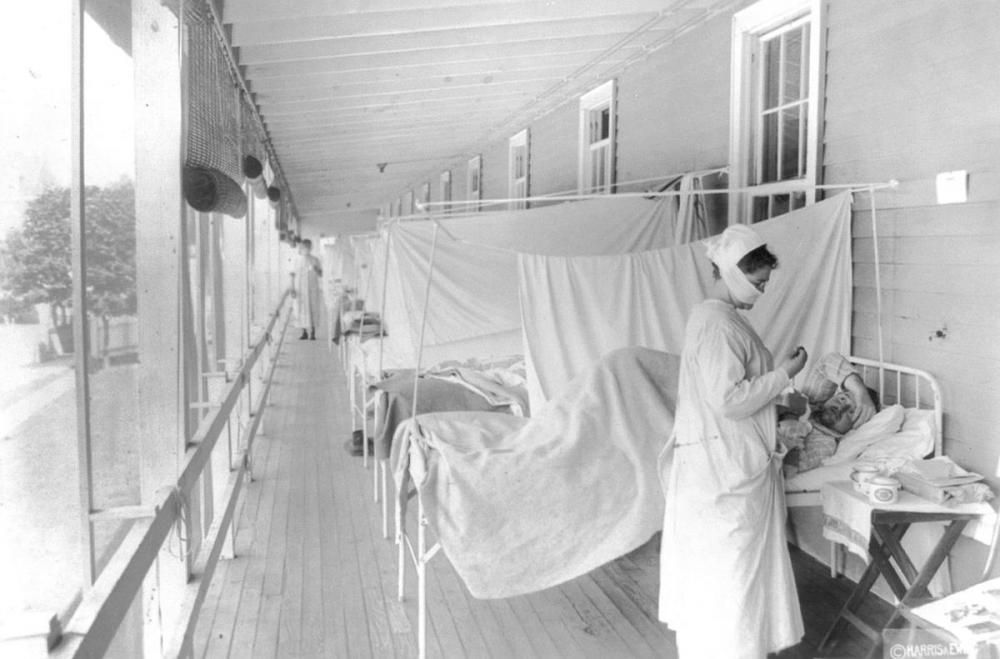

This week, the Spy got a call from Bob Aswell, a resident of Somerset County, who wanted to share a little known story about the devastating impact from the 1918 flu.

His grandmother, Lillian Sterling, was widowed in World War I, when her husband, Milton Byrd died from gas poisoning. To support her three children, she worked at the seafood processing plan, Handy & Sterling in Crisfield.

Times were unimaginably difficult then, and the hardy people of that era looked forward, never backward. But she wanted to make sure that her grandson never forgot the devastation from the 1918 pandemic. To stop the spread of the disease in Crisfield, its dead were transported and buried on James Island, next to the plant. She quit counting at 383, but others counted over 500 nameless souls buried on that island, their lives marked by simple wooden crosses.

The crosses are gone now, washed away by storms and decay; but the smokestack from the plant remains, a hallowed memory of the loss and destruction that a pandemic can cause.

Angela Rieck says

It should be Janes Island, not James Island