There’s nothing like a fresh pair of eyes to help us see our familiar surroundings anew, and “Rivers,” a captivating show at Kent Cultural Alliance on view through September 7, provides them, times four. Ashley Minner Jones’s recording of lapping waves with occasional birdsong brings the beauty and serenity of our rivers instantly to mind, while Hilary Lorenz’s fascinating paper weavings speak of their animated complexity. William Blake’s paintings contemplate the ongoing legacy of the Civil War along their shores, and Langston Allston’s two large canvases examine rivers as paths to freedom.

In partnership with ShoreRivers, KCA sponsored a six-week residency for the four artists, all from different parts of the U.S. During the first week, they received an intensive introduction to the area. They each spent a day on a river with one of ShoreRivers’ Riverkeepers, toured Chestertown with a focus on the history and influences of the river on the community, learned about local ecology from ShoreRivers and Sultana Education Foundation staff at the Lawrence Wetlands Preserve, and visited conservation projects on a waterside farm dating back to the Colonial era.

From there, the artists were free to react to their experiences by creating art, and each one chose an entirely different approach.

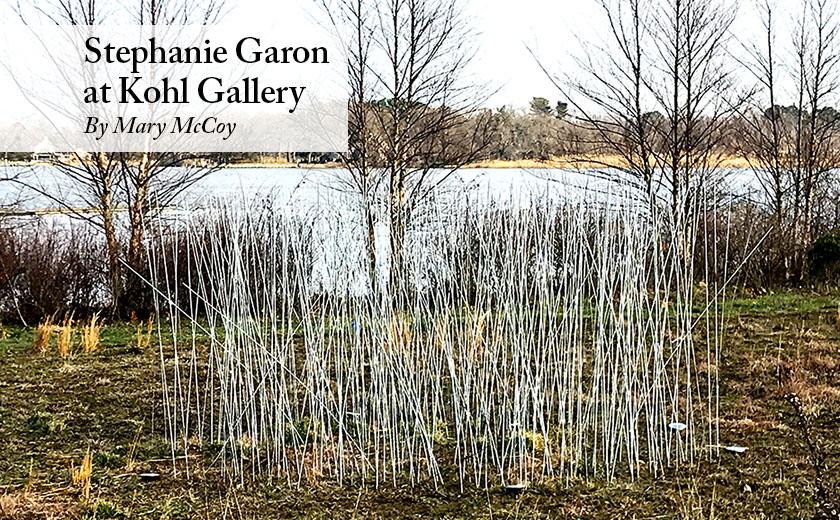

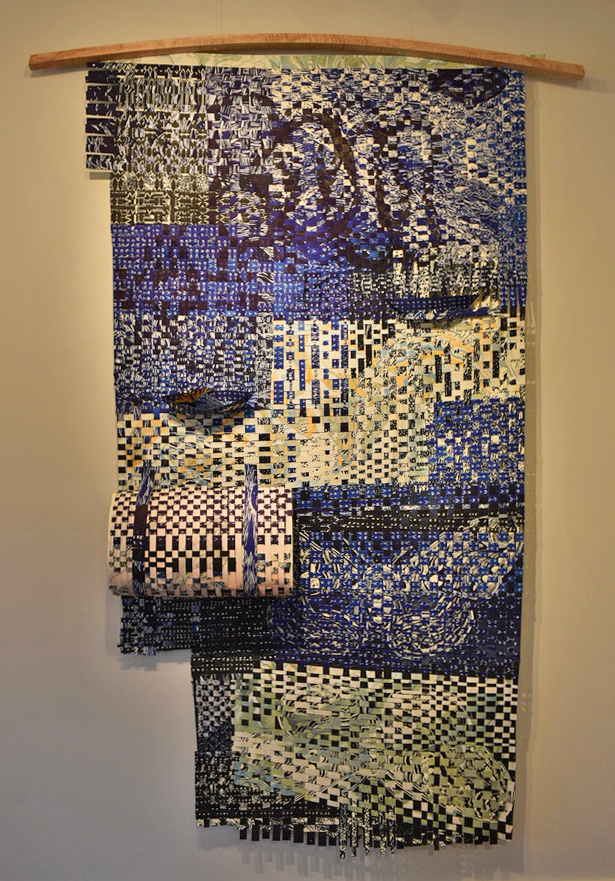

“Waves at the Edges of Nowhere” by Hilary Lorenz

For Lorenz, an interdisciplinary artist whose studio is in the high desert of Arizona, weaving seemed the perfect analogy for the coming together of the myriad influences that create our rivers’ ecosystems. Stunningly complex and dynamic, her series of works created from paper hand-marbled in water from the Chester River woven together with vividly patterned stone lithography and linoleum block prints evoke the ever-changing ripples and waves, shadowed depths and sudden sparkling glints of light on a tidal river. Sometimes the weaving folds over on itself like a breaking wave or reveals a fringe of seaweed cut out of paper dangling down from behind, sometimes a shape appears—a heart or an enormous moth, a remnant of an image from one of the prints. It’s like watching a river flow—the more you look, the more you discover.

More gentle but hardly less complex, Lorenz’s row of hand-marbled cloths are graceful studies of the movements of wind and water. Working outdoors, mostly in Wilmer Park, Lorenz used the traditional Japanese suminagashi method of dabbing colored ink rhythmically onto water she had scooped from the river. As with her hand-marbled paper, she allowed the wind to swirl the ink into natural patterns, capturing the whirls of color by laying cotton cloths on the water’s surface. Multiple layers of marbling yielded bafflingly complex waves and whirlpools as intricate as the ripples, eddies and flow of the river itself.

“River Brought Me to You” by Langston Allston

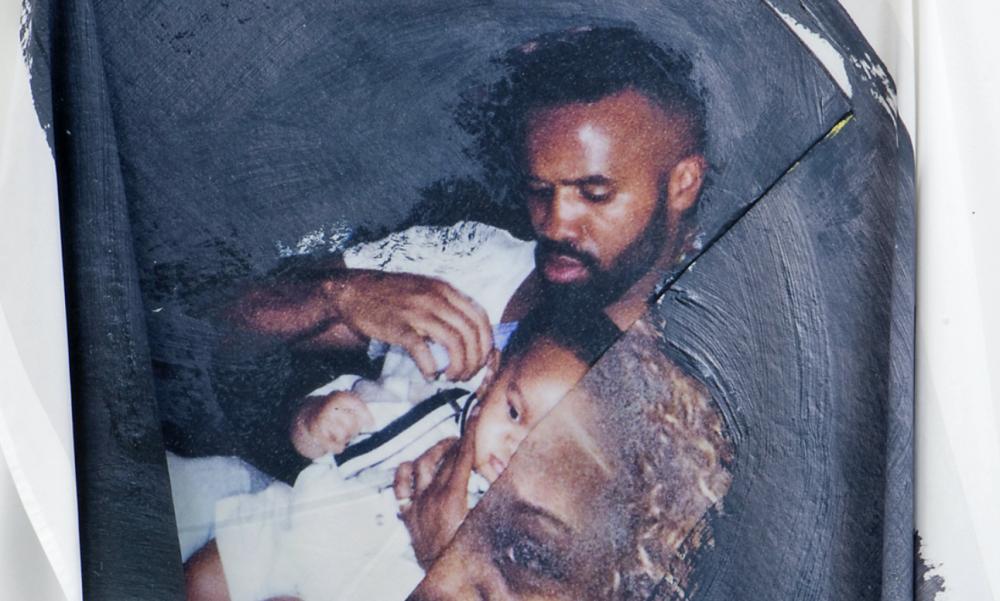

Minner Jones also took a hands-on approach to “Rivers” gathering both native and invasive plants from the Chester River watershed and grinding them into powders that she mixed with vodka to create a photosensitive emulsion of each species. To make her “Chestertown Anthotypes,” she laid a sprig of each plant on paper brushed its particular emulsion and exposed it to sunlight for 14 days. The resulting prints have a subtle, touch-your-heart beauty that can’t help but draw you in to study their graceful leaves, flowers and berries, forging an intimate connection with the individuality of each plant.

A community-based artist and folklorist, Minner Jones has lived her life in a Baltimore neighborhood settled by members of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, of which she is a registered member. While looking through the Kent County Historical Society’s archives, she came across a headline from a 1995 issue of The Cecil Whig asking “What happened to the Shore’s Indians?” The question appears three times, pointedly unanswered, as empty white lettering hovering in a field of brushy color, either the deep blue of cyanotype, the rich gold of the powdered remains of black-eyed Susan plants (the state flower of Maryland), or the sandy brown of Chestertown soil.

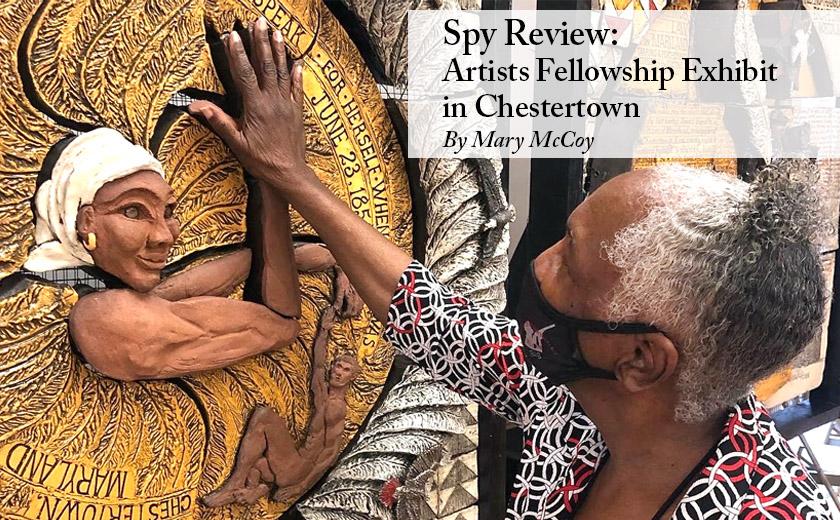

Blake, a painter who lives and teaches near Chicago, has carved out a curious niche for himself as a Civil War reenactor who paints other reenactors. Purposefully echoing Winslow Homer’s documentation of the war during his service as an artist-correspondent, his skillfully rendered subjects conjure a hauntingly engaging sense of introspection about a conflict that continues to reverberate down to the present day.

In a striking trio of ink and wash paintings, Blake casts the fiery abolitionist John Brown as “Father Time,” inviting consideration of the morality and repercussions of Brown’s actions as seen from our 21st century perspective. In contrast, the river appears a magical place in three oil paintings of a pair of reenactors dancing together on its shores under a full moon, a sprinkling of glittering stars, or a comet (in reference to the comet of 1861 which some saw as a kind of portent relating to the war). Full of hope and joy, these scenes exude a strong optimism about our progress in understanding equality and inclusion.

It’s in another oil painting, “A Sense of History Comes Not by Sight,” that Blake’s message comes most to the fore. In loose brushwork coalescing into robust flesh tones, a man clad in a Civil War uniform is painted eyes closed, clearly contemplating the lessons of history, something we all would do well to emulate. With a bristling gray and white beard, he is of an age to have gained perspective, and in a mischievous play on the idea of reflection, Blake paints light glinting off his forehead and from under his glasses. Clearly, it’s the light that shines with the dawning of understanding.

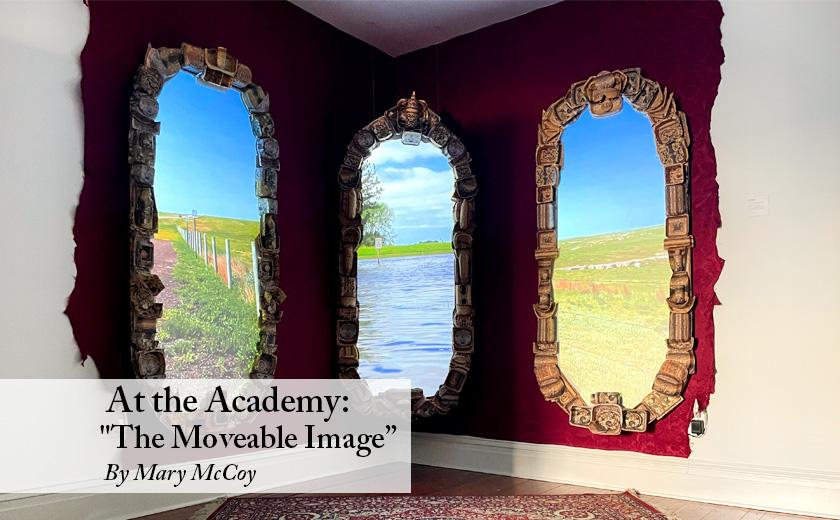

Allston’s two large canvases casually hung on grommets have a bold, visionary energy that recalls the directness of folk art. A painter and muralist who works in both New Orleans and Chicago, he used the river as the setting for both works. In “Fourth of July,” the faces of two young African Americans are lit by the glow of fireworks so strongly that the light becomes stars blooming on their dark skin as if to say, “This is our country, too!”, a potent reminder of those whose forced labor was crucial in building the country from Colonial times onward. In his second painting, “The River Brought Me to You,” the two faces of a figure in a small boat look both forward and back as he paddles furiously on a dark river surrounded by shadowy, foreboding woods. Swooping in from above in a rush of green flames, three winged women, like the Greek Furies, urge him onward.

Framing these arresting images are small drawings and handwritten notes scrawled in urgent capital letters that serve as a journal of Allston’s encounters, thoughts, emotions and discoveries during his residency. In an off-hand, stream of consciousness style, they range widely, describing encounters with a local elderly white woman who apologized for her ancestor’s involvement in the Ku Klux Klan, his musings at the sight of a stately historic home across the Choptank River, and his wandering homesick thoughts about the effects of the Mississippi River on his home in New Orleans. Integrating personal experiences with the influences of history and geography, his ponderings suggest a tapestry of interlocking stories.

Typically, artist’s residencies allow artists to immerse themselves in their work in a supportive, inspiring environment where they can connect with other creative individuals, but KCA’s residency has added purpose. The artists were called to explore rivers in ways that informed them and constantly engaged them with the community. They worked with young people in RiverArts’ summer camps, painted a mural at Worton Community Center, collaborated with local craftsmen, hosted open studios, gave talks about their work, and built new relationships.

The ripple effect is clear—in the process of creating art in response to what they learned through the residency, the artists have gifted our community with new and richer ways to understand our rivers and experience a firmer sense of place. And in a further benefit, as they return to their own homes, these artists will continue to disseminate their insights in their future work, benefitting people in many other communities and helping us all to better understand one another.

For more about Kent Cultural Alliance, go here.