Imagine the thrill for an artist like me when the director of a major museum made a point of congratulating me on one of my sculptures. I can still see her back then in 2011, a small, sparkly woman with long blond hair and an oversized glittering necklace looking up at the shiny, tattered, slightly muddy, beribboned string of stray balloons I had draped back and forth across the corner of the gallery. That was how I first met Rebecca Hoffberger, of the American Visionary Art Museum.

The truth was, however, that meeting her at a reception for an art show at Howard County Center for the Arts wasn’t exactly going to advance my career. Her museum exhibits the work of people who, unlike me, haven’t been to art school and don’t show their work in galleries. Instead, they make art because of a burning need in their spirit.

On February 21, the Spy partnered with the Academy Art Museum to present a talk by Hoffberger. In this overview of the AVAM’s history and mission, she made it clear that she feels there’s more to art than what we normally see in white-walled galleries and urged us to think less about the finished product and more about art as an open-ended, no-holds-barred investigation and celebration of what our world is all about. You can find out more in these two articles here and here on the Spy, but what I want to do here is tell you more about Hoffberger herself.

She’s a visionary. There are plenty of articles online that will tell you about her colorful life and how her response to the paintings and drawings of institutionalized psychiatric patients sparked her ideas for the museum. Deeply moved by the passion behind their raw creativity, she felt a compulsion to establish a venue where art born of an intuitive need for creative expression could be seen and considered. Recognizing art as a basic human need, the AVAM has dedicated itself to art that follows “the intuitive path of learning to listen to the small, soft voice within.”

I’m an art critic, as well as an artist, and in spending many years looking at art and talking with artists, I’ve been continually reminded that almost all artists do begin by listening to that “small, soft voice,” but too often, we’re pulled off track. In our culture, to earn your stripes as a “real” artist, you pretty much have to attend art school and be indoctrinated in (mostly Western) art history, then build a substantial resume of gallery exhibits, grants, awards and residencies, and remember to use words like “ontology,” “visceral” and “deconstruction” whenever possible. These expectations have made contemporary art into an insular, privileged activity. There’s too much background knowledge required for most people to appreciate gallery art, much less enjoy it.

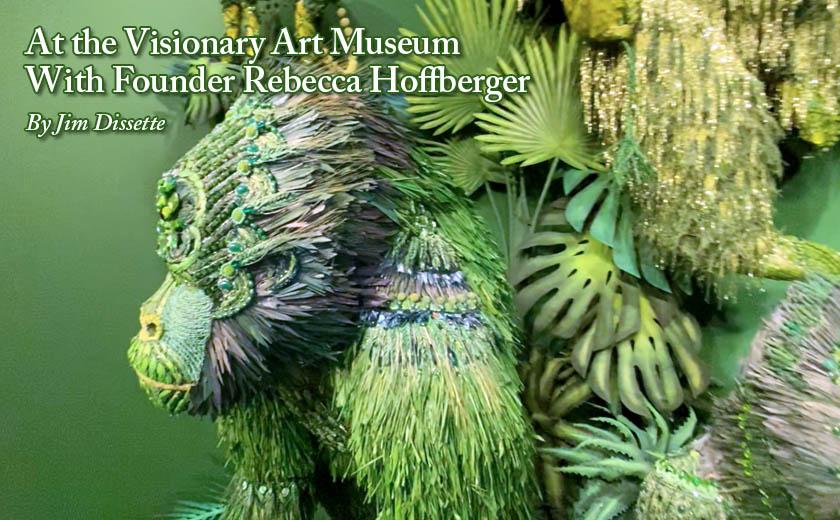

Hoffberger doesn’t bother with that kind of stuff. She keeps a very active eye out for people who just plain need to make art, whether they call it art or not, and this is what sets the AVAM apart from most art museums. For example, my friend, Trams Hollingsworth, who is a gardener and rescuer of eagles, raccoons and crows, is a featured artist in the AVAM’s current exhibit, “The Secret Life of Earth: Alive! Awake! (and Possibly Really Angry!). When I asked her how Hoffberger knew about the pigeon skeleton she lent for the exhibit, she said she had made it her business to befriend Hoffberger after a trip to the AVAM bowled her over.

“I stalked her,” she explained. “I started writing these love notes, like ‘You taught me so much in one day and I can’t teach you anything except how to do nothing and I’m pretty sure you’re not very good at that.’ Then we started corresponding and then maybe five years ago there was this really big snow storm. I got a call and she said, ‘This is Rebecca and I’m really tired and I want to take your Master’s course in doing nothing. I’m gonna get snowed in with you.’ And she did—five days snowed in.”

Rebecca Hoffberger has that effect on people. She makes you look at things differently, and like any good teacher, she is not aloof and never hesitates to ask whatever she likes. So at a small party at Trams’s house the evening before Hoffberger’s talk, when she overheard me say something to Trams about the aftereffects of having had brain surgery, she broke off her own conversation to ask, from across the room, how the experience had changed me. A brief conversation and a few days later, I found myself having lunch with Pat Bernstein, who had also undergone brain surgery. We had a fascinating talk comparing notes about how my experience had led me to lose my fear of spiders, heightened my appreciation of being alive, and made me hate sugary food, while hers had caused her to suddenly start seeing faces in trees and rocks. Impelled to document them, she had gone to Hoffberger for suggestions on how to share the resulting series of photographs with the public and ended up with her photos included in the AVAM’s “Earth” show.

Hoffberger’s talk at the Academy Art Museum was titled “Welcome to Wonder,” as apt a description of her outlook as of the AVAM’s infectious celebration of awe, outrageousness, pathos, obsession, and joy. Quick of mind and full of enthusiasm, she’s also full of stories. Spurred by her warmth and openness, I overcame my shyness and invited her to visit our studio the next day on her way back to Baltimore. It was a quick visit, but before it was over, she had shared anecdotes about the children’s train at the Wanamaker store in Philadelphia, Ronald Reagan’s psychic, Ohio’s Serpent Mound, how corn developed from a grass-like plant bearing a row of tiny pyramid-shaped kernels, and how pawlonia trees absorb eleven times more carbon dioxide than other trees.

We did a thorough tour of the studio as we talked, but we didn’t look at the sculpture she liked back in 2011. It’s currently stuffed into a big bag, but it has doubled in length since Hoffberger saw it. I feel kind of like one of her visionary artists who are impelled to make art because I can’t help but continue working on it. It irks me that I’m forever finding wayward balloons caught in the stubble in the fields of my family’s farm and tangled in the marsh grass along the river, so I tidy them up, carry them back to the studio, and incorporate them into what is now a nearly 50-foot-long sculpture. I’ve exhibited it four times so far and hope to do so again because, as Hoffberger and her museum have reminded me, we need to follow that urge to make art.

My personal soapbox is for the environment, but as a trip to the AVAM will bear out, there are myriad ways that art can help us examine the realities of life. More than simply a means of celebrating beauty and creative skills, art is a process through which we can explore, clarify and inspire a sense of value in shared social and spiritual significances. In our age of fractured relationships, confused priorities, hate-mongering, population pressure, and environmental degradation, we need plenty of art. We need to do what Hoffberger and the AVAM advocate and tune our senses so that the “small, soft voice” can be heard.

Mary McCoy is an artist and writer who has the good fortune to live beside an old steamboat wharf on the Chester River. She is a former art critic for the Washington Post and several art publications. She enjoys the kayaking the river and walking her family farm where she collects ideas and materials for the environmental art she creates, often in collaboration with her husband Howard. They have exhibited their work in the U.S., Ireland, Wales and New Zealand.