The sycamore tree in front of our house is a summer friend, but at this time of year, it tries my patience. Just yesterday, I was raking its detritus in the morning when a neighbor walked by and pointed up at all those leaves still on the bough. “Why bother?” she said. She had a point, but I looked around and muttered, “We’ve all got work to do.”

The sycamore tree in front of our house is a summer friend, but at this time of year, it tries my patience. Just yesterday, I was raking its detritus in the morning when a neighbor walked by and pointed up at all those leaves still on the bough. “Why bother?” she said. She had a point, but I looked around and muttered, “We’ve all got work to do.”

Don’t get me wrong: I like leaves as much as the next guy or gal, at least up until they become a Sisyphean chore at this time of year. Then all that summertime shade gets dumped on the porch, on the lawn, on the sidewalk and in the gutter, and suddenly I’m under a blanket of problems. Makes me want to stay in bed, pull up the covers, and pretend it didn’t happen.

But “it” did.

Why do I even bother to rake up all this debris? Well, for starters, dead leaves block sunlight and prevent photosynthesis, the process that would provide the grass under the leaf pile with all the nutrients it would need to regenerate in the spring. In other words, all those dead and dying leaves just smother and starve my little lawn, making it difficult, if not downright impossible, for new grass to grow come April. And then there’s this: dead leaves promote disease by blocking air circulation which can lead to turf rot. So, despite all those leaves that are still clinging to the limbs above me, I pick up my rake and get back to work. There’s a lot to do.

I suppose I could just mulch all those leaves with my lawnmower. Mulching would at least turn all those downed leaves into a thin layer of organic material that would be beneficial for all the microorganisms that help to spin the cycle of life. The only problem with that strategy is its aesthetic value. A mulched-leaf lawn looks like I’m shirking my good neighbor responsibilities, plus it’s a steep and slippery slope that only leads to sloth.

Autumn is, by nature, our most melancholy season. As I rake my leaves into tidy piles, I can’t help but think of Robert Frost’s mournful poem, “Nothing Gold Can Stay:”

“Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.”

In her concession speech, Vice President Harris reminded us that this is not the time to throw up our hands, but to roll up our sleeves. So instead of listening to the pundits’ endless analyses and recriminations, I’ve decided to turn off the television for a while and work. Now, I go outside to rake leaves. There’s a certain satisfaction that comes with yard work, a sense of purpose, an end that justifies the means. I suppose i could just let all those dead leaves accumulate, but passivity makes a cold supper. Work warms.

This shadow, too, shall pass. After all, everything eventually does. The Greek philosopher Heraclitus put it this way: “the only constant is change.” The People have spoken and I will respect their loud voice. In the meantime, I’ll be outside, sleeves rolled up, raking leaves.

I’ll be right back.

Jamie Kirkpatrick is a writer and photographer who lives in Chestertown. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Baltimore Sun, the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the Washington College Alumni Magazine, and American Cowboy Magazine. His new novel, “The Tales of Bismuth; Dispatches from Palestine, 1945-1948” explores the origins of the Arab-Israeli conflict. It is available on Amazon.

This delicate balance between simplicity and power is a hallmark of Horstman’s work. She strives for images that offer viewers a visual reprieve. “I guess it’s just that your eye isn’t darting everywhere,” she explains. “It doesn’t take a lot of energy to look at it—it just feels calm. When there’s too much going on, I want to move on.”

This delicate balance between simplicity and power is a hallmark of Horstman’s work. She strives for images that offer viewers a visual reprieve. “I guess it’s just that your eye isn’t darting everywhere,” she explains. “It doesn’t take a lot of energy to look at it—it just feels calm. When there’s too much going on, I want to move on.”

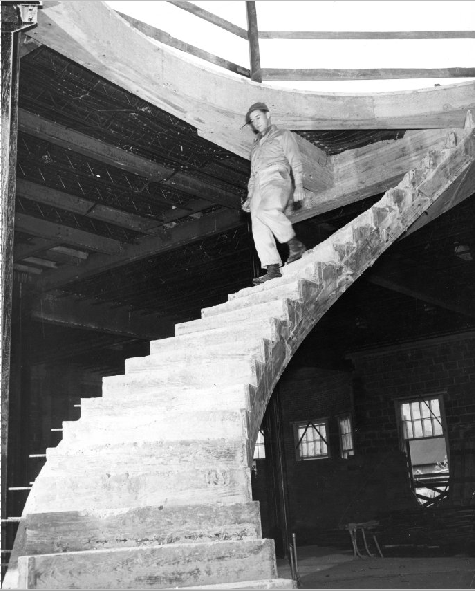

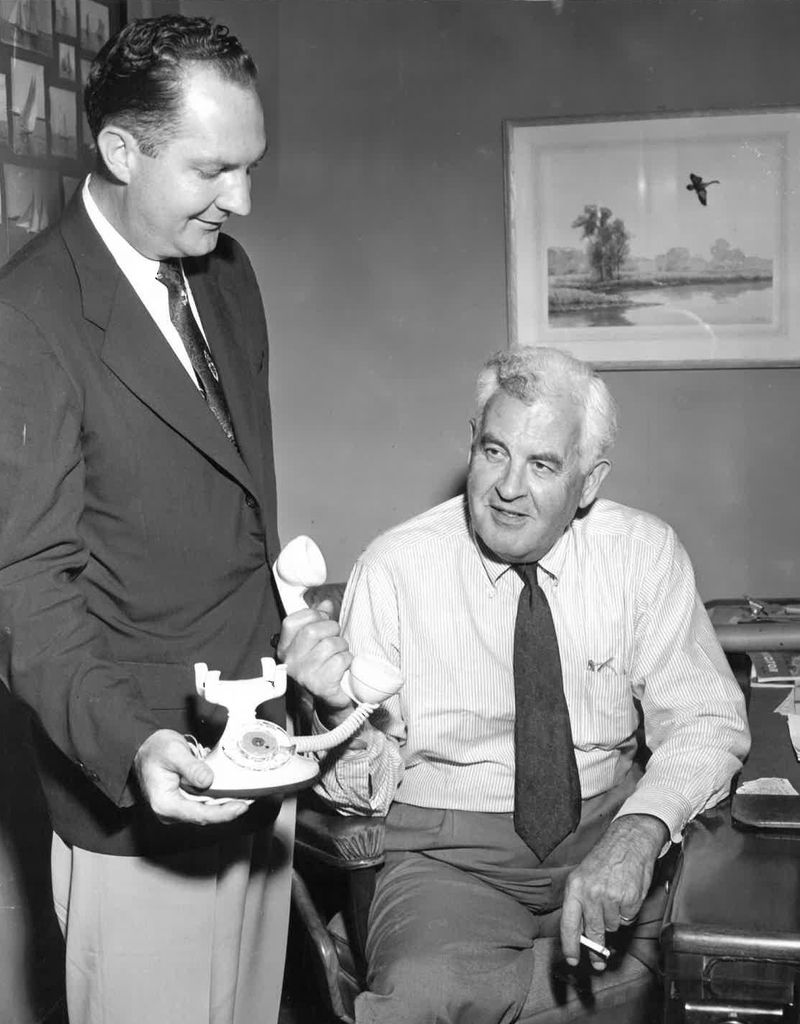

The Tidewater Inn’s design was inspired by the Williamsburg Inn, blending a high-style plantation aesthetic with the relaxed rural hospitality of local estates such as Wye House. This hospitality extended to the Maryland House and Garden Pilgrimage in 1949 and beyond, where guests could board hunting dogs in hotel kennels. The hotel reflects the tension between modern and traditional aesthetics, rural and urban space, and the southern and northern views of a border state.

The Tidewater Inn’s design was inspired by the Williamsburg Inn, blending a high-style plantation aesthetic with the relaxed rural hospitality of local estates such as Wye House. This hospitality extended to the Maryland House and Garden Pilgrimage in 1949 and beyond, where guests could board hunting dogs in hotel kennels. The hotel reflects the tension between modern and traditional aesthetics, rural and urban space, and the southern and northern views of a border state.