- When we moved to the farm cottage in our early thirties, we were capable in spirit but clueless in reality. Neither of us had any real experience. I’d worked on a flower farm for a few months, been mostly successful tending a collection of potted herbs on the back of the wooden sailboat we’d called home, and knew a little about how to sell an idea. He was an avid eater and skilled carpenter with a side helping of engineering prowess. Beyond that, we weren’t bringing much to the stewarding table.

When it came to food production, enthusiasm and good intentions would carry us only so far. The rest we’d have to learn.

It was one thing to figure out how to grow marketable vegetables and flowers, quite another to get the hang of caring for chickens. And the roosters, bless their hearts, were like trying to play chess with a tornado. Not only were they unpredictable, they were faster, stronger, louder, and more committed than we were. Somehow, we found our way.

We started with an existing small flock before graduating to mail-order chicks. Early on a Sunday morning, we’d get a call from the postal distribution center in the next town over — because that’s how things work in a rural community — and we’d dash off to pick up our peeping box of day-olds. A few deliveries and turns around the sun later, we were tending over a hundred laying hens, and there was almost always a rogue rooster in the mix. We never knew whether the hatchery was testing our mettle or was persistently staffed with practical jokesters.

Before we knew some of these birds would try to kill us. Note the shipping box!

Whatever the case, we ended up with Peeper. Formally “Outside Peeper,” because he had a knack for escaping. Fences that worked for the other birds were nothing to him. He slipped through every opening, darted around every obstacle, flapped over every barrier. He was always crossing boundaries and coloring our world completely outside the lines.

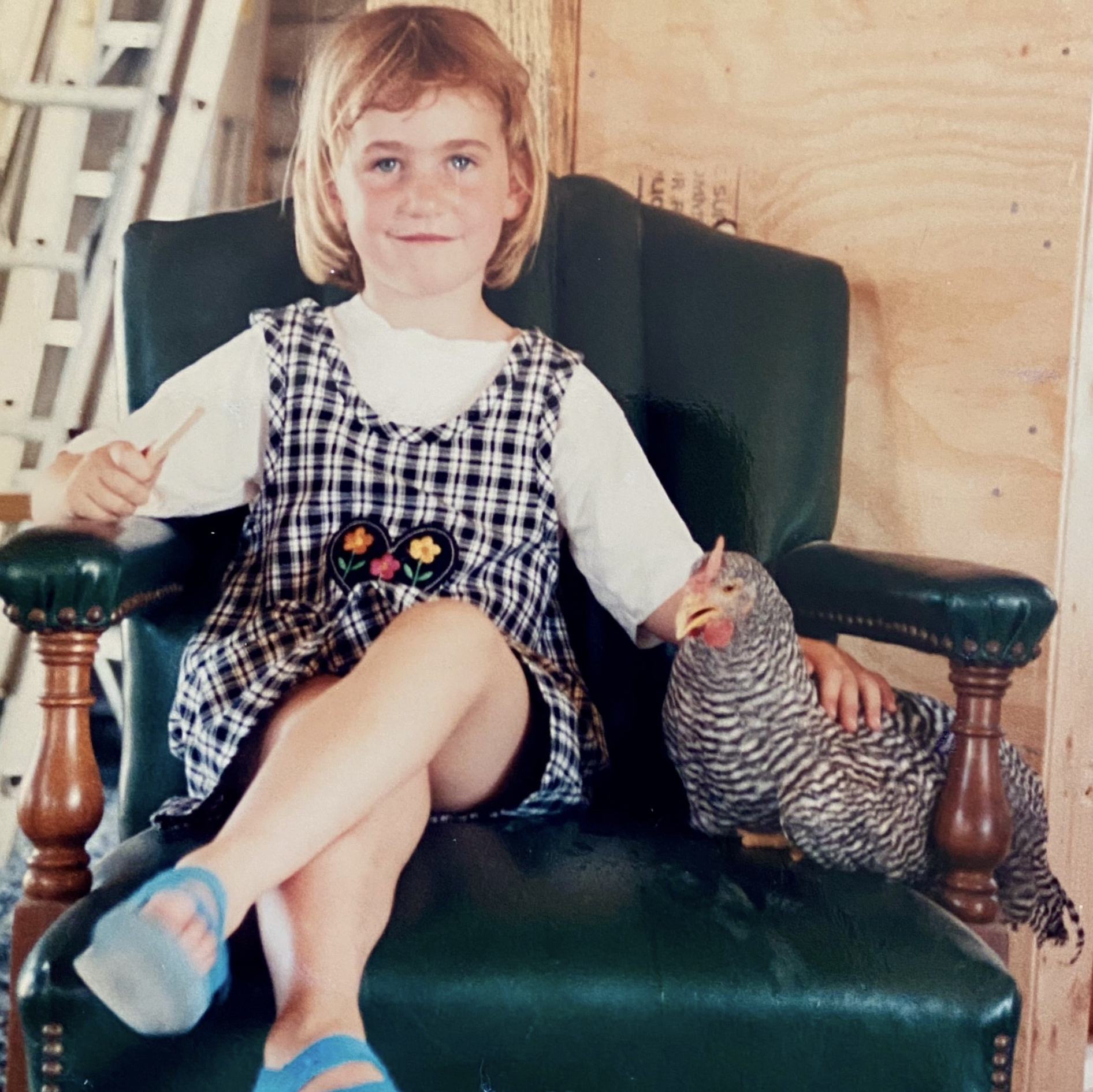

You might wonder why we gave a rooster such a wimpy name. Partly, because our daughter named him when she was five. She tended to be literal, and he did peep for a while, like they all did. But also, we didn’t know he was a rooster until the day he crowed.

In time, we’d learn to spot the telltale signs: longer neck feathers (called hackles), a taller comb, extra leg length, an arrogant strut. But birds don’t come with external plumbing, and it takes a few months for the other differences to become obvious. Looking back, he was distinctive from the start — slightly lighter plumage than the pullets, a bit more upright in posture — which meant he was easy to spot even when he wasn’t on the wrong side of the coop. Otherwise, he was just another future egg layer.

And we made a rookie mistake: we let our kid get attached. Not that we had much power to stop her, but we didn’t even try to discourage it. No efforts to remind her that farm chickens aren’t usually around for the long haul. No gentle parenting disclaimers folded into bedtime stories.

Innocent kid. Peeper, plotting to take over the world.

Before we knew it, we had a pubescent pet cockerel on our hands — and our legs, and our lunches. Peeper had an overachiever’s approach to protecting his flock, charging anything that moved within twenty-five feet. This was less of an issue before his spurs grew in.

For the uninitiated, all chickens come with small bumps on the back of each leg. Male hormones cause these to grow into bony, keratin-covered spikes, like a leg beak or a miniature jousting lance. Spurs can be trimmed and rounded, but when you don’t know shit from shineola about chickens, that’s not the first thing on your to-do list. Soon, the rooster gets the upper hand, or leg.

Say you’ve got a gaggle of little girls eating tuna sandwiches and apple slices on a blanket in the yard. Suddenly, shrieking, scattering, and there’s Peeper, strutting through the wreckage like a conquering warlord. Score one for the rooster.

Or say you and your husband are both running defense. He played ball sports as a kid and usually manages to land a warning kick. You, on the other hand, always react a second too late, and end up looking ridiculous. So you arm yourself with a giant stick, but you can’t collect eggs and pour feed while waving a weapon, so mostly you’re just trying not to get spurred in the shins. Score another one for Peeper.

But say on this particular day you’re cruising along in your trusty farm vehicle, a repurposed golf cart, when you see Peeper running toward you at full speed. There’s no way to know if he’s out for food or blood, so you shoot your leg out the side of the cart in preparation for a strike. The feathered linebacker fakes left, then right, then cuts directly into your path before you can react. At the moment your foot slams down on the brake pedal, you hear a noise that sounds like a cross between a whoopie cushion and Tarzan.

You’ve flattened your daughter’s pet rooster.

In my defense, I stopped before he was completely overrun. I’m not even sure the farm cart could have surmounted him, given his size. I felt us roll backward and was both relieved and mortified to see Peeper pop out, stand up, and gimp toward the neighbor’s house, possibly hoping to find a better arrangement. Intelligent bird.

Later that evening, he made his way back to the coop where I was able to examine him more closely. It appeared I’d injured little more than his pride, and this was confirmed the next day when he was back to his same cantankerous self again, although he did give us a wider berth than usual for a few days.

Eventually, something had to give. Peeper wasn’t mellowing with age, and we were tired of getting ambushed. Friends up the road had hens roaming freely on open pasture, with rival roosters and plenty of space. It seemed like a good fit. These were folks who felt it was the natural order of things to keep a male with the ladies. Conflicted, I shared that opinion with a different friend, who simply looked at me, raised an eyebrow, and said, “Why?” This is why we are still friends.

Now the only hurdle was breaking the news to our daughter. We didn’t give her a choice, but we tried to explain: No more looking over her shoulder for a blur with double-barreled leg-daggers. No more stolen sandwiches. She could visit him from time to time, if she wanted to.

It was the first of many times we’d name a rooster, hope it might understand the difference between a hazard and a helper — and be proven wrong. But it was the last time we let affection run that far ahead of practicality

Recently, I heard author Sy Montgomery (you might know her for The Soul of an Octopus) on a podcast talking about her newest book, What the Chicken Knows, now on my list to read. In it, Montgomery shares what she’s learned from keeping chickens, and what she’s learned from people who go even deeper. One of them is her neighbor, who runs a rooster rescue. This woman swears by an unorthodox method for dealing with aggressive roosters: pick them up and carry them around. Cuddle them. Smother them with affection. Let them know who’s boss, but also let them feel adored. Eventually, she says, they turn, mellow out, even become downright charming. Some bring gifts, shiny things, bits of string, and follow their humans around like puppies.

I laughed when I heard it. Then I pictured myself walking the farm with Peeper tucked under my arm like a pampered Pekingese. The image of that still makes me chuckle. But also, I kind of wish I’d tried it, not that I had the time or the patience.

I did see evidence of what Sy Montgomery described. I watched my birds form friend groups, remember routines. I heard Peeper sound alarms when hawks passed overhead, and trill like a waiter announcing the daily special when he found something good to eat. I saw him step back to let his ladies take the prize, and I saw him charge anything that threatened them, including us.

They were brilliant at being chickens.

Turns out the best photo of Peeper was glued to a kindergarten collage project.

Peeper probably wasn’t a problem rooster, just a very committed one. He took his job seriously, whether or not we liked the way he did it. Chickens descend from Asian jungle fowl, who themselves carry the legacy of dinosaurs like the velociraptor and T. rex. When I consider that, Peeper’s behavior makes a lot more sense.

Looking back, I wonder if it wasn’t actually us who needed rewiring. I’m sure much of what we did made no sense to those birds. We changed their rules, built boundaries we expected them to respect while stepping over theirs.

It’s possible that chickens find us infuriating. Honestly, I wouldn’t blame them.

An audio version of this essay, read by the author, is available here.

Cover image by Arthur Oscar SchillingCommunity Archives – Barred Plymouth Rocks, Public Domain

Elizabeth Beggins is a communications and outreach specialist focused on regional agriculture. She is a former farmer, recovering sailor, and committed over-thinker who appreciates opportunities to kindle conversation and invite connection. On “Chicken Scratch,” a reader-supported publication hosted by Substack, she writes non-fiction essays rooted in realistic optimism. To receive her weekly posts and support her work, become a free or paid subscriber here.

Rob Etgen says

Great story Elizabeth! Our “Peepers” was named “Daisy.” Daisy got so aggressive my wife and daughters could not get out of the house. Alas, Daisy became Coq au vin!

Elizabeth Beggins says

Ah, Daisy. I guess there was some earned dignity in the fact that our daughter chose a gender-neutral name. Here’s hoping they both came back in the next life to owners who had the time and patience to carry them around. Thanks for sharing your story, Rob!

Alan Girard says

Elizabeth, you might remember the chickens we had at Pickering Creek when you and I first met. They came in a box much like the one in your photo. Got stabbed more than a few times there, too.

Elizabeth Beggins says

Good thing they start out small and cute, eh? Here’s to the whole chicken-tending learning curve! Thanks for the comment, Alan.