One of the great, little-known crimes against humanity in 2025 was the BBC’s decision to block access to its radio broadcasts outside the United Kingdom. The stated reason was copyright concerns and the threat of litigation, which effectively shut down the BBC Sounds app for international listeners. Whatever the legal rationale, the result has been the loss of access to some of the most enriching and engaging programming in radio—particularly the documentaries and series produced by BBC Radio 3 and Radio 4.

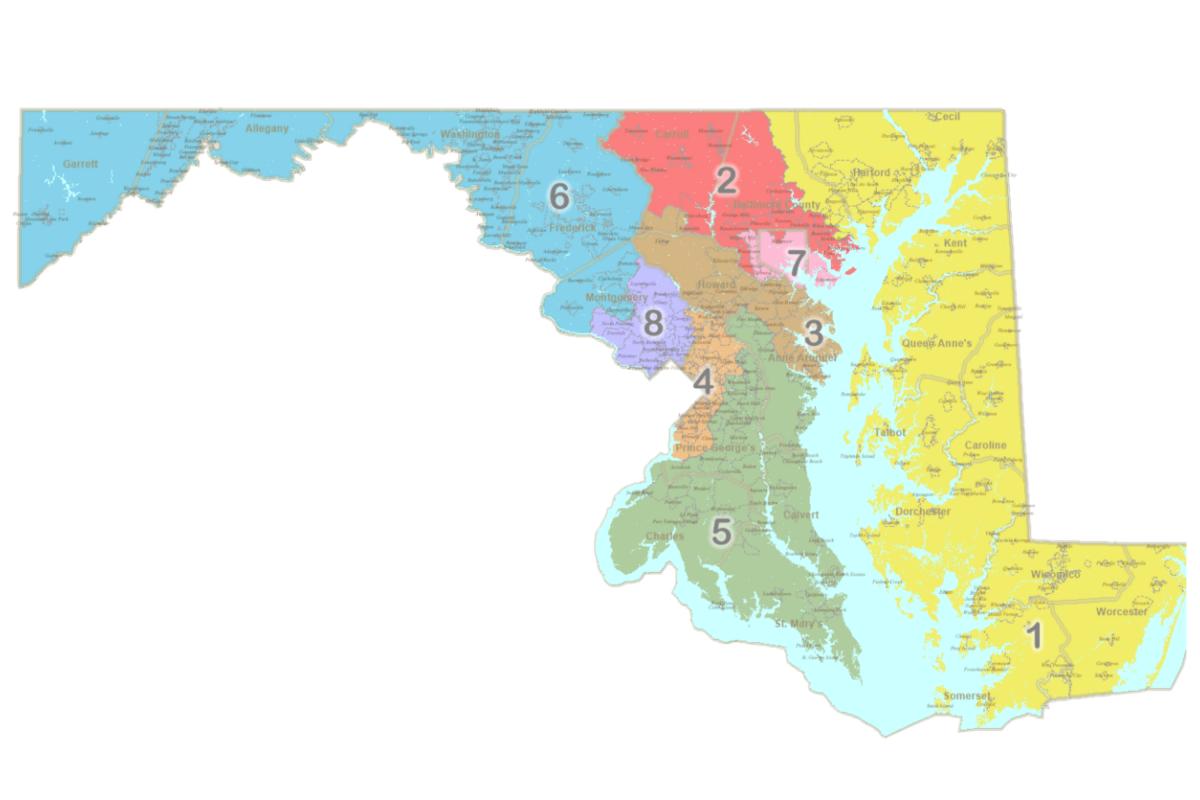

There is, however, a simple workaround. By using a VPN to make your computer or phone appear as though it is located in England rather than, say, the Eastern Shore of Maryland, full access is restored. I encourage Spy readers to do just that and hear for themselves some of the best moments of our shared Western culture. I’ve included a brief “how-to” link below for anyone with a bit of holiday time and curiosity to spare.

There are countless programs to recommend, but the one I have been listening to over the past two days, which has given me so much personal joy, is BBC Radio 4’s series celebrating the 100th anniversary of the publication of A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh, entitled Who Are You in Winnie-the-Pooh?

Illustration by Albertine Randall Wheelan

It includes interviews with well-known British children’s writers who spoke about why A. A. Milne’s stories still matter and why every human being should love this bear.

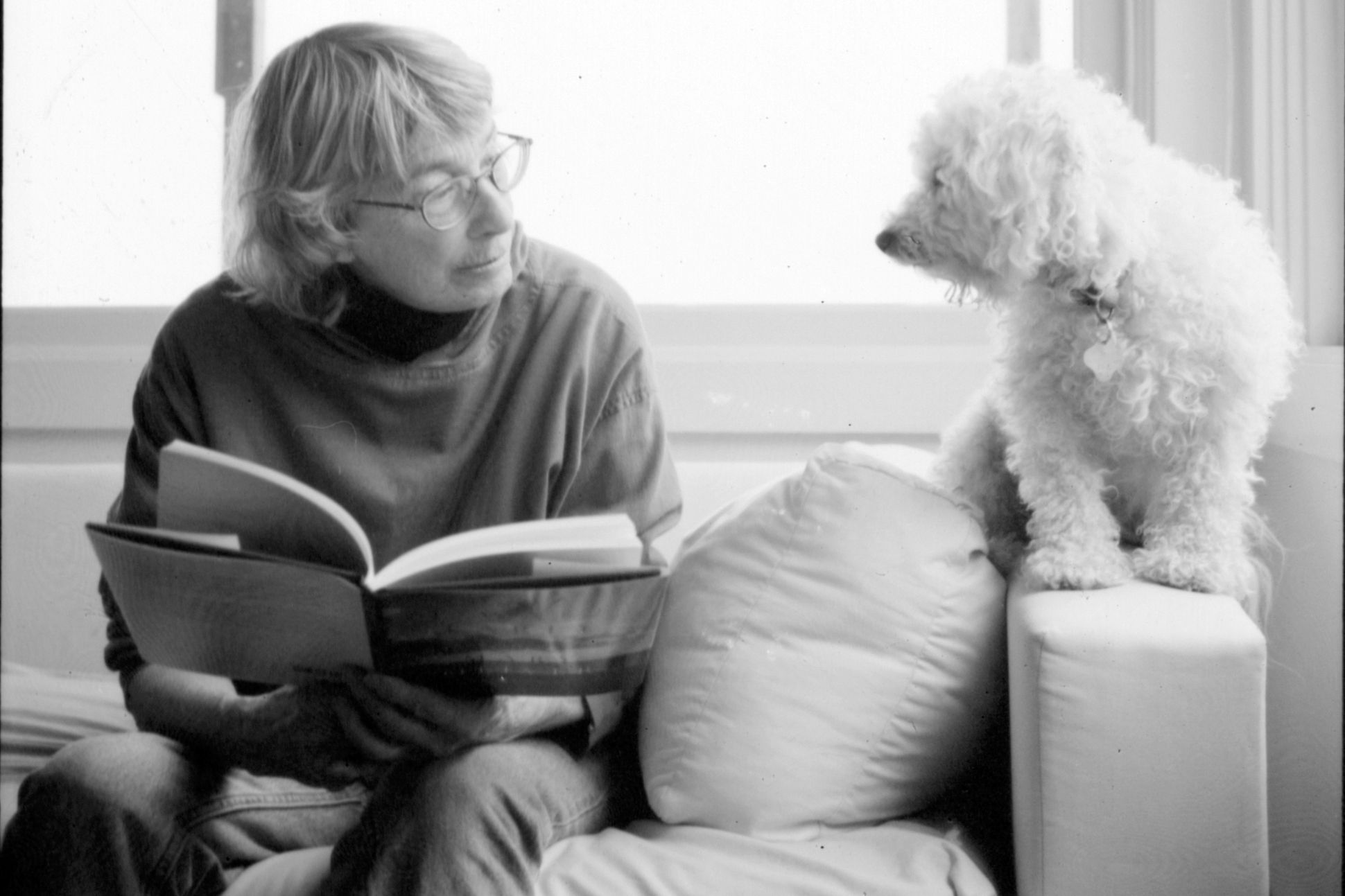

While I can’t recall any parental readings of the classic during my childhood, my family had a well-established love of bears, starting with one of our most cherished family objects: my great-grandmother’s illustration in St. Nicholas magazine in February 1909, long before Pooh ever existed.

I’ve had a soft spot for bears ever since.

In the early 1980s, during long drives through rural New England with my then-wife’s friend Karen, we often found ourselves without radio reception. To pass the time, we took turns reading aloud to each other and quickly agreed that humor was important. It was Karen who suggested we read Winnie-the-Pooh. Upon revisiting it as an adult, I discovered that it contains some of the sharpest, kindest, and most enduring humor imaginable, regardless of age.

Like many readers of the stories and guests on the show, I aspire (but rarely succeed) in being a bit like Pooh. Humble in intellectual capacity (“I am a Bear of Very Little Brain”), devoted to his friends (“We’ll be friends forever, won’t we, Pooh?” said Piglet. “Even longer,” Pooh answered), ready for revelry (“Nobody can be uncheered with a balloon”), and yes, always finding time for a “little something” to eat (“I wasn’t going to eat it; I was just going to taste it.”)

The ideal Pooh moves through the world without edge or pretense. He doesn’t judge, doesn’t scheme, and rarely rushes.

And Pooh gives us advice as we grow older and friends depart.

“Pooh, promise you won’t forget about me, ever. Not even when I’m a hundred.”

Pooh thought for a little.

“How old shall I be then?”

“Ninety-nine.”

Pooh nodded.

“I promise,” he said.

Still with his eyes on the world, Christopher Robin put out a hand and felt for Pooh’s paw.

“Pooh,” said Christopher Robin earnestly, “if I—if I’m not quite——” he stopped and tried again—“Pooh, whatever happens, you will understand, won’t you?”

“Understand what?”

“Oh, nothing.” He laughed and jumped to his feet. “Come on!”

“Where?” said Pooh.

“Anywhere,” said Christopher Robin.

So they went off together. But wherever they go, and whatever happens to them on the way, in that enchanted place on the top of the Forest, a little boy and his Bear will always be playing.

In the end, Winnie-the-Pooh endures not because it is clever, but because it is kind. It reminds us that friendship matters, that joy can be found in small rituals, and that being present for one another is its own form of wisdom. As the world grows louder, faster, and more certain of itself, Pooh offers a quieter example—one rooted in patience, affection, and the simple grace of showing up. Returning, even briefly, to the Hundred Acre Wood is not an escape from adulthood, but a way of remembering what makes it bearable.

You can learn how to get BBC radio in the United States by watching this video.