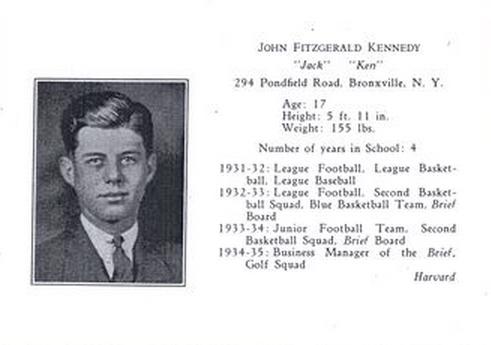

Last month, November 22 was the 62nd anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy (JFK).

To this day, there are countless unresolved “what if” questions about that day in Dallas.

What if JFK had not gone to Dallas in the first place? What if JFK’s schedule had been limited to a speech at an indoor banquet hall and did not include a slow-motion open-roof ride through downtown Dallas that had more challenges for security and safety? What if he was shot by multiple assassins who were recruited by a conspiracy and not by a lone deranged assassin?

All we know with absolute certainty is that President Kennedy died that day, and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) was immediately sworn in as his successor.

That raises a post-assassination “what if” question. What if JFK had lived and disapproved or reversed previous decisions on additional American ground troops in a civil war in Vietnam?

Obviously, we will never know with absolute certainty the answer to that “what if” question.

We can make some informed assumptions based on presidential historian Robert Dalek’s book, “An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy 1917-1963.” Dalek includes a riveting review of deliberations with, and decisions made by JFK on the recommendations of his foreign policy and military advisors during the “Cuban Missile Crisis” in October 1962.

This crisis began when JFK was told that the former Soviet Union was placing nuclear missiles in Cuba that were capable of destroying huge sections of the continental United States.

For thirteen days, there was widespread public uncertainty and fear that, after a decades-long cold war between America and the former Soviet Union, this crisis could lead to a nuclear war.

JFK immediately convened a series of meetings with the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, whose members included his National Security Advisor, Secretary of Defense, Secretary of the Treasury, Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, the military’s Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy Sr., JFK’s brother and closest advisor.

During these meetings, military action was given serious consideration by all the attendees who shared a commitment to contain and even reverse the former Soviet Union’s efforts since the end of World War II to expand communism throughout the world.

Some suggest the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis resulted in part from an American Central Intelligence Agency scheme to recruit, train, and fund a group of Cuban exiles to invade Cuba and overthrow Fidel Castro’s communist government. That invasion was a spectacular failure and was a worldwide embarrassment for the Kennedy administration.

Despite that failure, JFK’s advisors discussed a military campaign that included bombings of the Soviet missile sites and air bases in Cuba, followed by another invasion of Cuba.

The October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis ended after thirteen days when an unexpected offer came to JFK from Soviet Union leader Nikita Khrushchev. The Soviets would remove missiles in Cuba if America removed U.S. missiles in Türkiye (then known as Turkey).

JFK viewed the request as reasonable and immediately expressed his support for it. With one exception, his advisors did not and continued to push for immediate military action in Cuba.

JFK’s Secretary of Defense endorsed the military’s Joint Chiefs of Staff plan that included steps needed before an attack on Cuba, as if attacks were inevitable and ready for final approval.

JFK’s National Security Advisor said, “I think we should tell you … the universal assessment of everyone in the government who’s connected with alliance problems—if we appear to be trading the defense of Turkey for the threat in Cuba, we will face a radical decline.”

Undaunted by this almost universal opposition to a diplomatic compromise, JFK rejected military strike recommendations. Instead, he directed his brother Robert to relay his agreement to Moscow, even though RFK strongly opposed Khrushchev’s compromise.

In doing so, Kennedy exercised his authority as President and Commander in Chief, much like Abraham Lincoln did during the American Civil war.

At one cabinet meeting, Lincoln presented his proposed change in strategy to help end the Civil War and asked his cabinet members to vote on it. Lincoln reported there were seven no votes and his yes vote. He then said the yes vote has it.

In a review of Dalek’s book, Fred Kaplan, a veteran observer of American foreign policy, wrote that Dalek failed to address significant differences between JFK’s and LBJ’s presidential leadership experiences and leadership styles.

Kaplan suggested JFK grew increasingly unhappy with “expert advice” from his foreign policy and military advisors. As a result, going forward, he would make final decisions by trusting his own instincts.

Kaplan also suggests LBJ had limited dealings with those advisors, was insecure about trusting his own instincts and was overly deferential to his foreign policy and military advisors, many of whom were holdover Kennedy appointees who had firmly held views that American military action was the best way to address the spread of communism in the world.

In any event, both Dalek and Kaplan agree that if JFK had lived, he would have withdrawn American ground troops already in Vietnam and not approved future deployments.

I agree and believe such a decision could have avoided at least 58,000 American deaths with a deeply flawed war strategy, nationwide antiwar protests, including one where four students were killed and nine wounded. Vietnam also ignited a lack of trust in our national government to do the right thing the right way — a feeling still held by many in American society today.

David Reel is a public affairs and public relations consultant and a consultant on governance, leadership, and management matters exclusively for not-for-profit organizations. He lives in Easton.